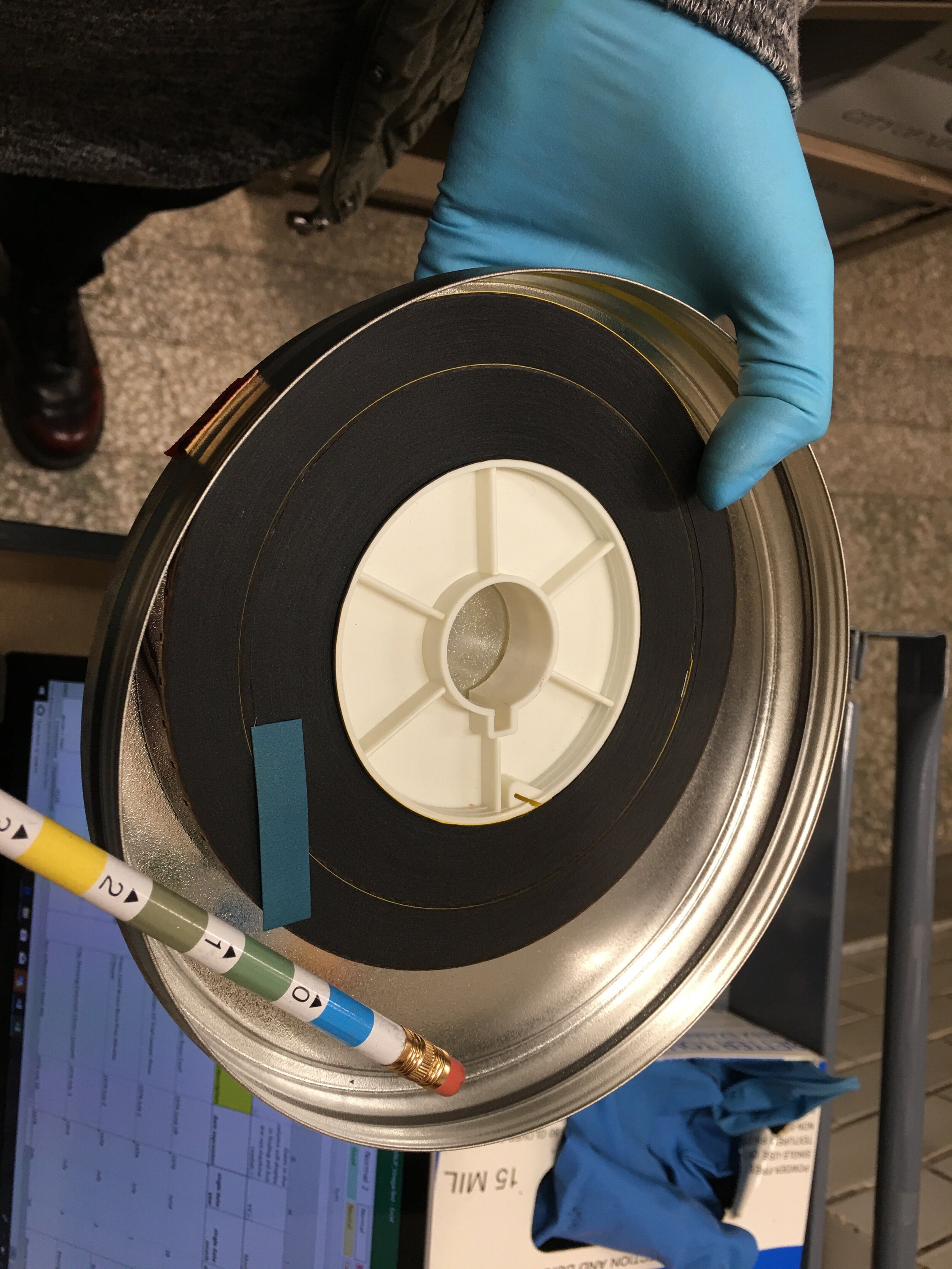

Nothing is immune to time, but as any preservationist can tell you, there are many possible actions to delay the process of deterioration and prevent an asset from disappearing into oblivion. Although considered fairly stable, especially when compared to video formats, 16mm films can be susceptible to physical damage (such as base and emulsion scratches, torn sprocket holes, etc.) as well as breakdown of the magnetic stock, mold, color dye fading, and—if cellulose acetate-based—vinegar syndrome. Vinegar syndrome, also known as acetate film base degradation, is characterized by a strong vinegar smell and eventually buckling, shrinkage, and weakening of the film. Since this reaction is autocatalytic, it is important to identify compromised films and prioritize them in preservation plans.

The WNYC-TV Film collection contains over 4,500 films. Although there are 35mm films in this collection, the majority is made up of 16mm films. With the LGRMIF grant, we aim to digitize close 900 films, creating master preservation copies, access copies, and providing content online.

When the Municipal Archives was awarded the Local Government Records Management Improvement Fund (LGRMIF) grant to digitize 16mm films from the WNYC-TV collection, it was clear one of the first steps of the project would be to identify which films were suffering from vinegar syndrome, and which ones were at the later stages of this reaction.

The WNYC-TV Film collection is currently housed with other collections in a room where the relative humidity (RH) can range from 39% in the winter to 60% in the summer, and the temperature is kept at around 70°F. As we know, the relationship between temperature and RH has a direct impact on how fast acetate-based films decay, and since the Municipal Archives has housed the collection for over 30 years, we expected many of the films to already show signs of decay.

The Image Permanence Institute (IPI) time contours graphic estimates how many years it takes for the onset of vinegar syndrome in acetate-based films.

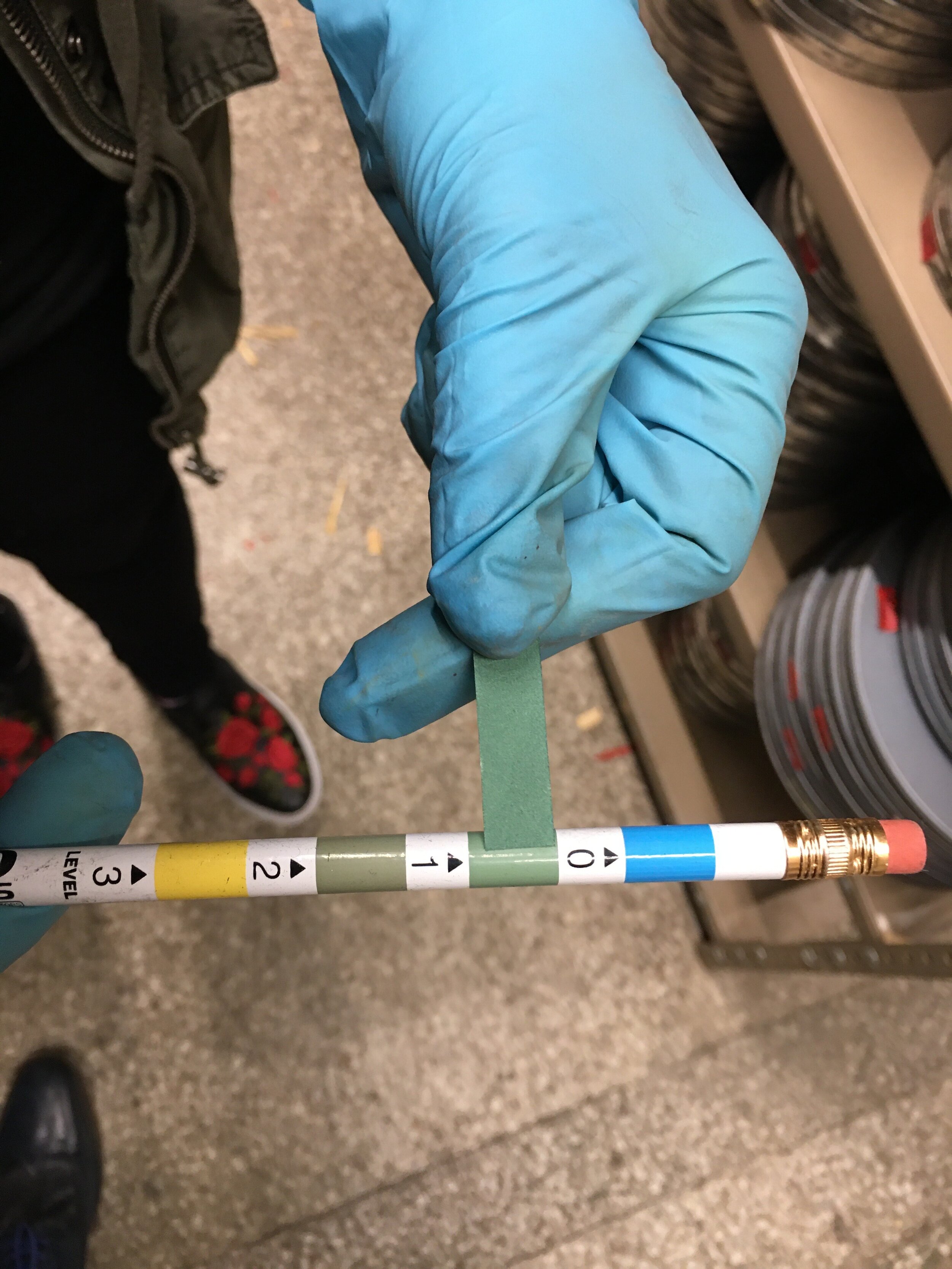

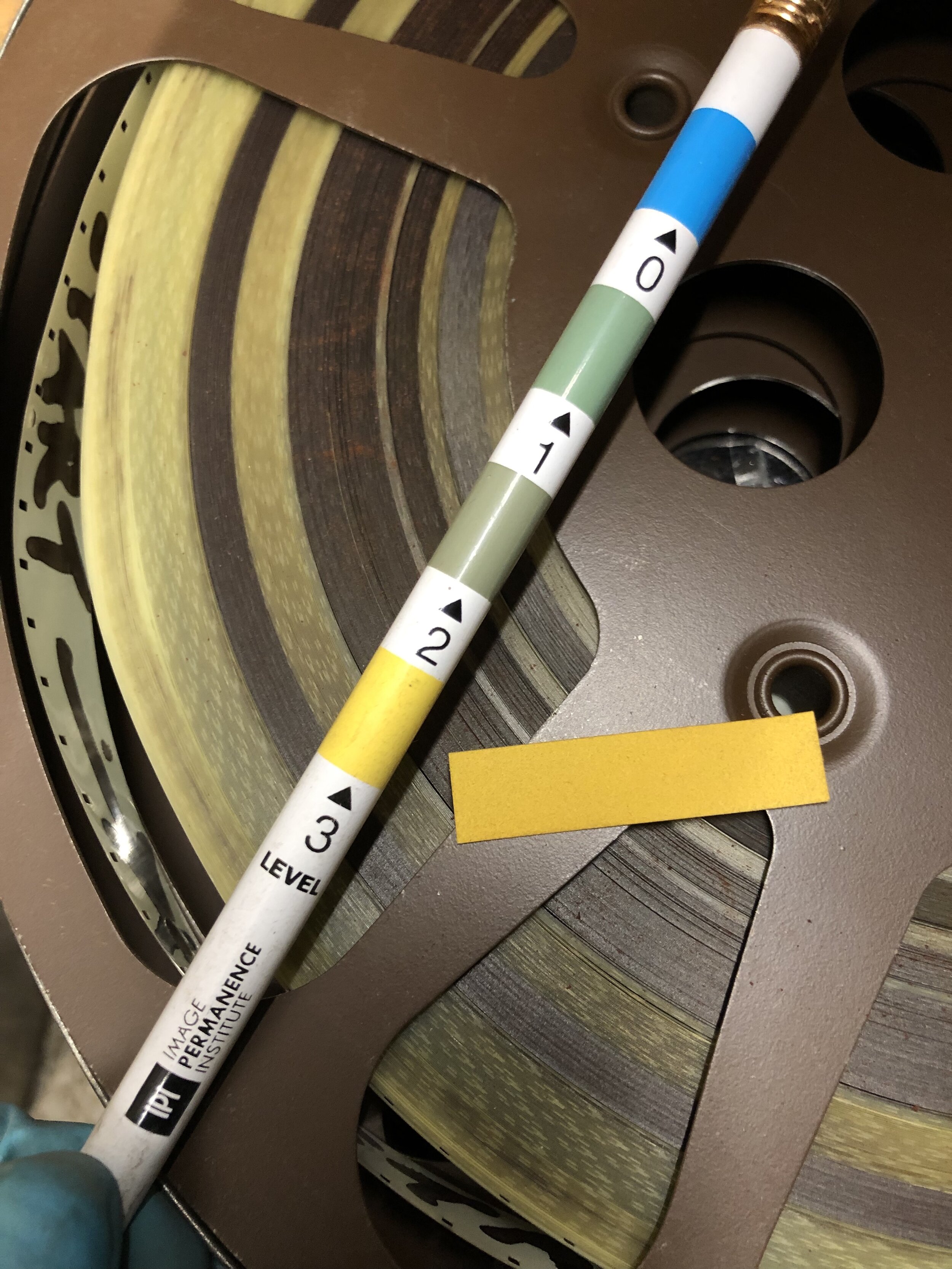

To test the films, we employed the use of A-D Strips—small paper strips coated in dye that react to the presence of acidic vapor. The strips change color from blue to yellow indicating the level of degradation of the film.

Because we have over 4,000 films in the collection and a limited amount of strips, we decided to run the A-D strip test in three phases.

Phase One consisted of placing from three to four A-D strips in each shelf dedicated to the WNYC TV collection, with one strip in each film can. We made sure to distribute the strips evenly, typically choosing cans that were in the middle of a stack. 251 films were tested during this phase and we kept careful documentation of which cans were being tested and the dates when the strips were placed.

A-D strips come with a handy chart, printed onto a pencil. Since color variations can be subtle during testing, it is helpful to take pictures and use them as reference.

A full day after we placed the A-D strips, we started retrieving them and checking each strip's color to determine the amount of acidic vapor it had been exposed to. The strips are compared to a color chart that assigns each color a numeric value representative of stages of film deterioration, from zero (blue) to three (yellow) with varying levels of green between.

Out of the 343 films tested during Phase One, we documented:

12 films scored 0.1

76 films scored 0.25

115 films scored 0.5

77 films scored 0.75

37 films scored 1.0

2 films scored 1.25

3 films scored 1.5

1 film scored 2.25

7 films scored 2.5

7 films scored 2.75

2 films scored 3

On Phase Two, we placed A-D strips on cans that were physically close to the ones tested during Phase One. The results were then documented 24 hours later and on the following days due to the high number of films being tested.

This phase produced some surprising results. Quite a few films that were located in close proximity to the ones that scored high levels during Phase One showed low levels of acidic vapor. Since these were sealed cans, the acidic vapors were most likely trapped in the can, adversely affecting the deteriorating film in the cans, but not spreading to the cans nearby. It would be interesting to investigate what other factors were keeping certain films healthy, even when located next to ones that were already showing signs of degradation.

We did notice some concentration on shelves where the older, sometimes even rusty cans were stored. It could be that the age of the films was key factor or perhaps the rusting cans were not air-tight and exposed the film to off-gassing and humidity fluctuations. Contrary, though, we also noticed higher levels in films stored in newer cans, which perhaps had been recanned at some point in an attempt to slow down degradation.

As a way to obtain more complete data on the collection, we used the remaining A-D strips on Phase Three, where we tested more than 200 additional films, focusing on shelves that had delivered higher scores. Over half of the films tested during this phase scored a 0.5 or higher.

Level three was noticed on magnetic tracks that carried sound effects, narrations, and music.

After compiling the test results from all three phases, we decided to prioritize all films that scored 0.5 or higher for digitization and recanning.

Although A-D strip testing can be considered slightly subjective as the reading of the test results is largely based on how the tester perceives color variation, it is a practical and nondestructive way to identify the severity of degradation in films. The process allowed us to create a prioritization plan for the next step in the efforts to preserve and increase access to the rich WNYC-TV film collection at the Municipal Archives.

Caroline Z. Oliveira is the film archivist digitizing the endangered WNYC films for a Municipal Archives project funded by the New York State Archives. Ms. Oliveira has already digitized much of the collection and the digitized content will be made available online sometime this year. Look for future blogs highlighting some of the footage in the collection.

Sources Reilly, James M. “IPI Storage Guide for Acetate Film,” 1993.