On April 3, 1936, Bruno Richard Hauptmann was put to death in the New Jersey State Prison at Trenton for the kidnapping and murder of Charles Augustus Lindbergh, Jr., the 20-month-old son of Col. Charles Lindbergh and his wife Anne Morrow Lindbergh. It was the end of one of the most sensational investigations in American history, except the case never really ended. Like other famous murders, such as the JFK assassination, it birthed a whole industry of conspiracy theorists who think that the police and FBI got it wrong. Even today, they are working to reopen the case and test evidence for DNA samples, and they have been the subject of credulous articles in publications as diverse as The New York Times and The Free Press.

Mugshot of Bruno Richard Hauptmann, September 21, 1934. NYPD Bertillon #128221, image courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

These articles are generally written based on information in the case files held by the New Jersey State Police. What is mostly overlooked, however, is that a large portion of the investigation took place in New York City, and that those records are in the Municipal Archives—the Bronx District Attorney closed case files and NYPD crime-scene photographs.

Reception Banquet Program for Charles Lindbergh, June 14, 1927. Mayor James J. Walker Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

After his 1927 solo flight from Long Island to Paris, Col. Charles Lindbergh won both fame and fortune. The $25,000 in prize money for the feat (which he shared with his backers), plus fees as a consultant and spokesperson for the now booming aviation industry made him a very wealthy man. By 1932, he had married the daughter of a diplomat, and they were living in Hopewell, New Jersey with their first child, a son.

Most sources agree on the essential facts of the abduction. On the night of March 1, 1932, the family nurse, Betty Gow, alerted Col. Lindbergh that she could not find his son. Lindbergh discovered that the child was missing from his crib and found a ransom note. The note demanded $50,000 for the safe return of the boy (about $1 million in 2025 currency). Soon after, he and the family butler noticed a hand-made ladder leaning against the second-floor bedroom window.

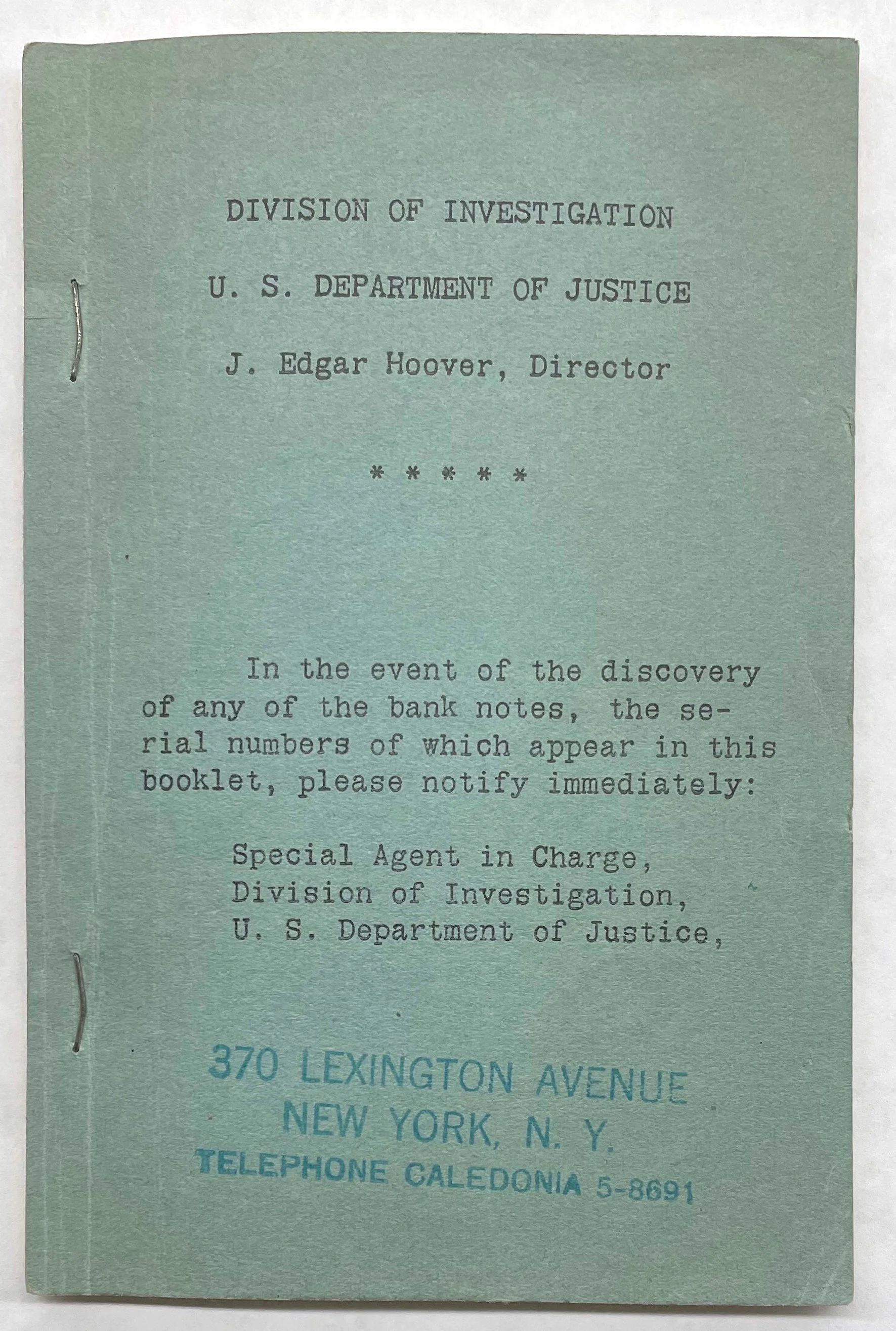

Almost from the start, the crime scene was mis-managed as the household and neighbors scoured the grounds looking for clues, perhaps trampling usable evidence. Then there was the press. They quickly descended on the property and the subsequent headlines whipped the public into a frenzy. President Herbert Hoover authorized the U.S. Department of Justice, Division of Investigation (DOI), precursor to the FBI, to investigate. Sleuths, both real and amateur, volunteered their services and offered opinions to the press. A huckster claiming to have inside knowledge of the kidnapping managed to talk heiress Evelyn McLean out of a sizable sum of money.

The first ransom note contained a mysterious symbol to identify future communications. On March 7th the Lindberghs received a second ransom note with the symbol, demanding $70,000. A third note was sent to Lindbergh’s lawyer. Both notes were postmarked from Brooklyn.

Photostat copy of a note passed to Dr. Condon during ransom negotiations. Lindbergh baby kidnapping closed case files, Bronx County District Attorney, NYC Municipal Archives.

Here the story shifts to New York. The third note asked Fordham University football coach Dr. John F. Condon to act as an intermediary to the exchange. A New York personality, Condon inserted himself into the case by offering his own reward for the safe return of the child. Condon received a note that instructed him to go to Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. Once there, a man arrived and introduced himself as “John” saying he was one of the kidnappers. Condon demanded proof the baby was alive and the man, who spoke with an accent, but kept to the shadows, said he would send the baby’s outfit by mail. After receiving the outfit, identified by Col. Lindbergh as belonging to his son, Condon again met with “John” and gave him a package containing $50,000 in small bills.

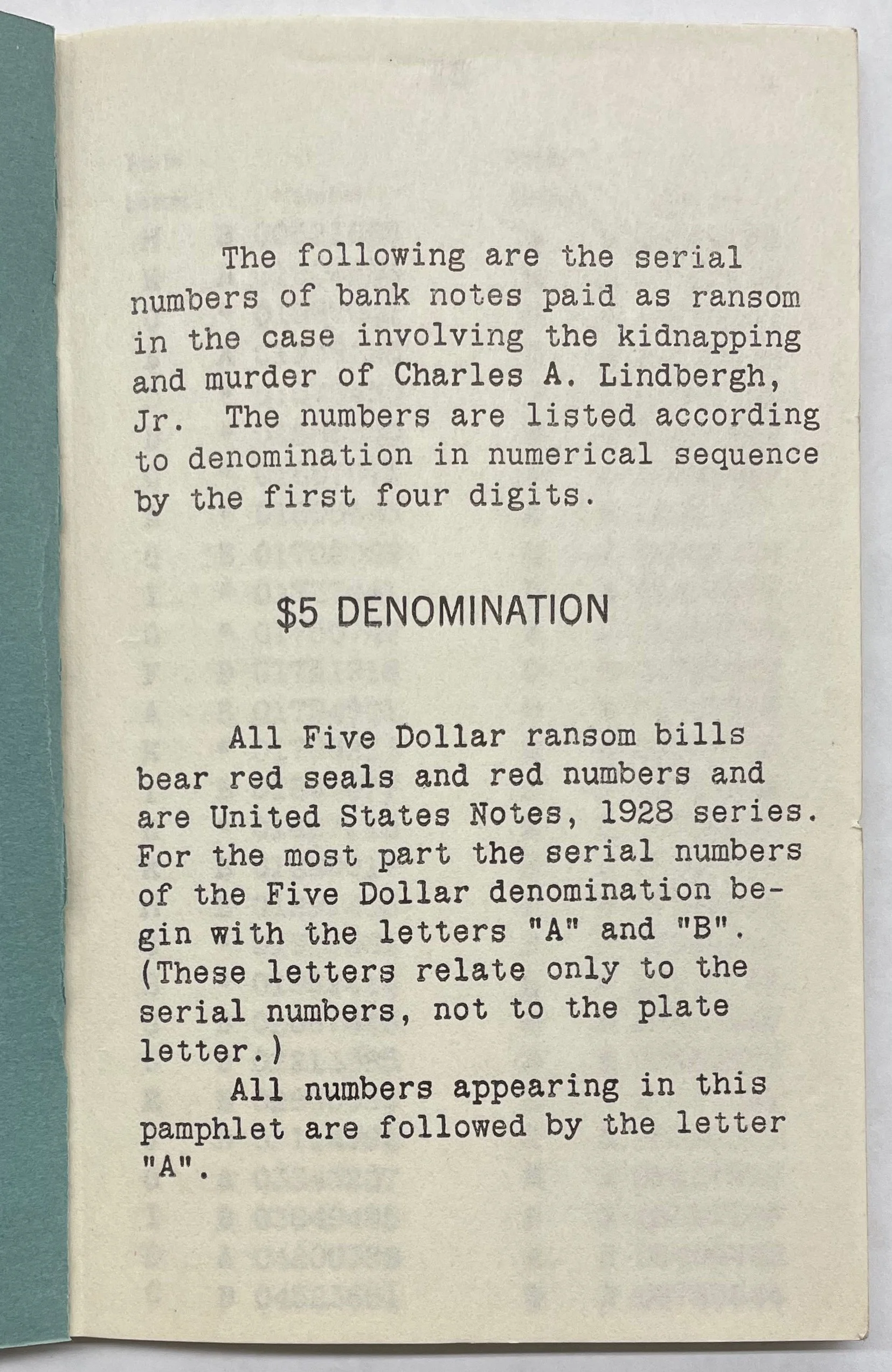

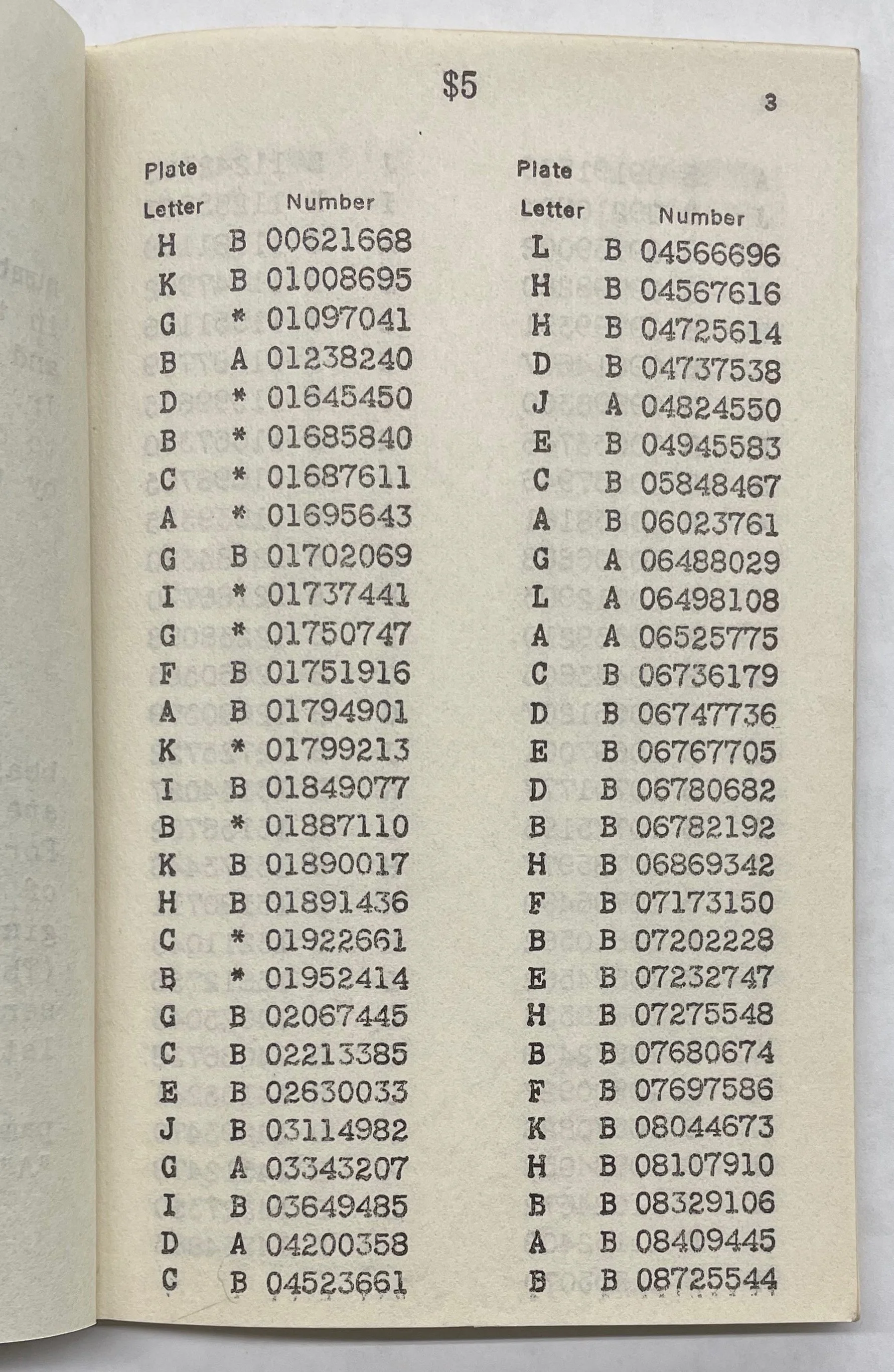

The currency had been carefully prepared. All the serial numbers had been recorded, and a portion of the bills were “Gold Certificates,” which were about to be discontinued as America left the gold standard. After this exchange on April 2, nothing further was heard from the kidnappers. On May 12, a truck driver pulled off the road near the Lindbergh house and went into the woods to urinate. There he found the remains of a toddler—it was the Lindbergh baby. And then, the case went cold.

Federal investigators distributed booklets with the ransom serial numbers to banks across the country. As they knew would happen, May 1, 1933, was the deadline for people to exchange gold certificates. A few days prior, a man exchanged almost $3,000, which turned out to be from the ransom money. He had given a false address at the bank, but other bills had been turning up in small amounts. The investigators noticed that they were spent along the Lexington Avenue subway line from the Bronx to the German neighborhood of Yorkville. Finally, on September 18, 1934, a bank teller spotted another gold note from the ransom. It was part of a deposit from a gas station and on it was written a number. The gas station attendant had found it odd that the driver paid with a gold note and had recorded the license-plate number of the car. The police now had a new suspect, the car’s owner, Richard Hauptmann of 1279 East 222nd Street in the Bronx. They quickly discovered that his real name was Bruno Hauptmann and that he had entered the United States illegally some years prior after a lengthy criminal record in Germany.

Police “mug shot” blotter book, 1934. Bruno Richard Hauptman [sic], B#128221, September 21, 1934. NYPD photo unit collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Lindbergh baby kidnapping closed case files, Bronx County District Attorney, NYC Municipal Archives.

Original NYPD negative sleeve, Lindbergh case.

The New York Police arrested Hauptmann on September 19, 1934, and obtained a warrant to search his property. The evidence they found was quite damning, including $14,590 in ransom money stashed in his garage, along with an unlicensed handgun. In his kitchen pantry, next to his phone, they found a scribbled phone number for John Condon. The investigators also took particular interest in wood boards from his garage that seemed to match wood from the ladder used in the kidnapping.

A Bronx Grand Jury indicted Hauptmann on September 26, 1934, for the crime of extortion. On October 19th, his case was transferred to New Jersey for a trial on the charges of kidnapping and murder. The Bronx District Attorney formally dismissed their case against Hauptmann in April 1936, citing his execution by the State of New Jersey.

NYPD_17576o: Premises at 1279 E 222nd St. where part of Lindbergh ransom money was found, September 21, 1934. Det. Dunn and Murphy, alien squad detectives on case. NYPD photo unit collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

New York Daily News, September 27, 1934. Lindbergh baby kidnapping closed case files, Bronx County District Attorney, NYC Municipal Archives.

NYPD_17576i: Garage at 1279 E 222nd St. where part of Lindbergh ransom money was found, September 21, 1934. Det. Dunn and Murphy, alien squad detectives on case. NYPD photo unit collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

NYPD_17576k: Garage at 1279 E 222nd St. where part of Lindbergh ransom money was found, September 21, 1934. Det. Dunn and Murphy, alien squad detectives on case. Police took samples of wood from the Hauptmann’s garage to match against the wood of the ladder used in the kidnapping. NYPD photo unit collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Telegram to Bronx DA, Samuel J. Foley from Federal investigators, September 24, 1934. Lindbergh baby kidnapping closed case files, Bronx County District Attorney, NYC Municipal Archives.

Much of the evidence in the case has been picked over and re-evaluated, and many books have been written, but the records in Municipal Archives provide a fascinating look into the investigation. The Archives received the papers in 1979 from the office of then-Queens County District Attorney Mario Merola. As the finding aid notes, “By the time they reached a staff processor in 1981, they had been rearranged, not entirely successfully, as part of a student intern project, and only seven (7) of the original envelopes remained to give some idea of the original order. They were marked as follows: ‘Lindbergh Old File S and B’; ‘Hauptmann D.J. Reports’; ‘Hauptmann 684-1934 Miscellaneous’; ‘Hauptmann Receipts’; ‘Hauptmann Reports, Letters, etc. Important’; ‘Statements Sept. 1934’; and ‘Translation of Letters Specimens of Writings.’”

NYPD_17576-1a: Piece of wood showing holes, Lindbergh case. Photographer: Gilligan #228. NYPD photo unit collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

NYPD_17576-1c: Revolver, Lindbergh case. Photographer: Gilligan #228. Police said they found this small pistol hidden in a piece of wood along with rolled up bills that were from the ransom money. NYPD photo unit collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

New York Daily News, September 27, 1934. Lindbergh baby kidnapping closed case files, Bronx County District Attorney, NYC Municipal Archives.

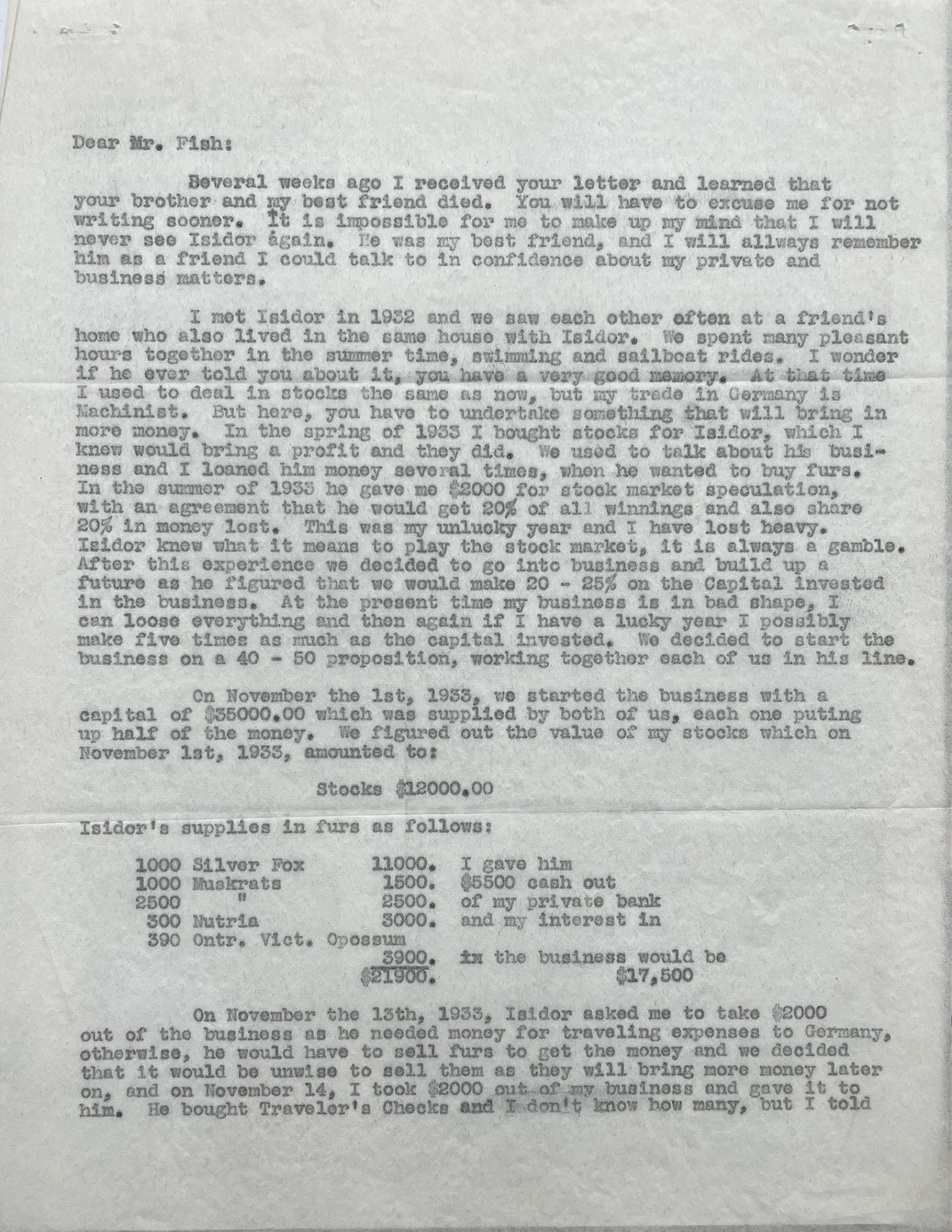

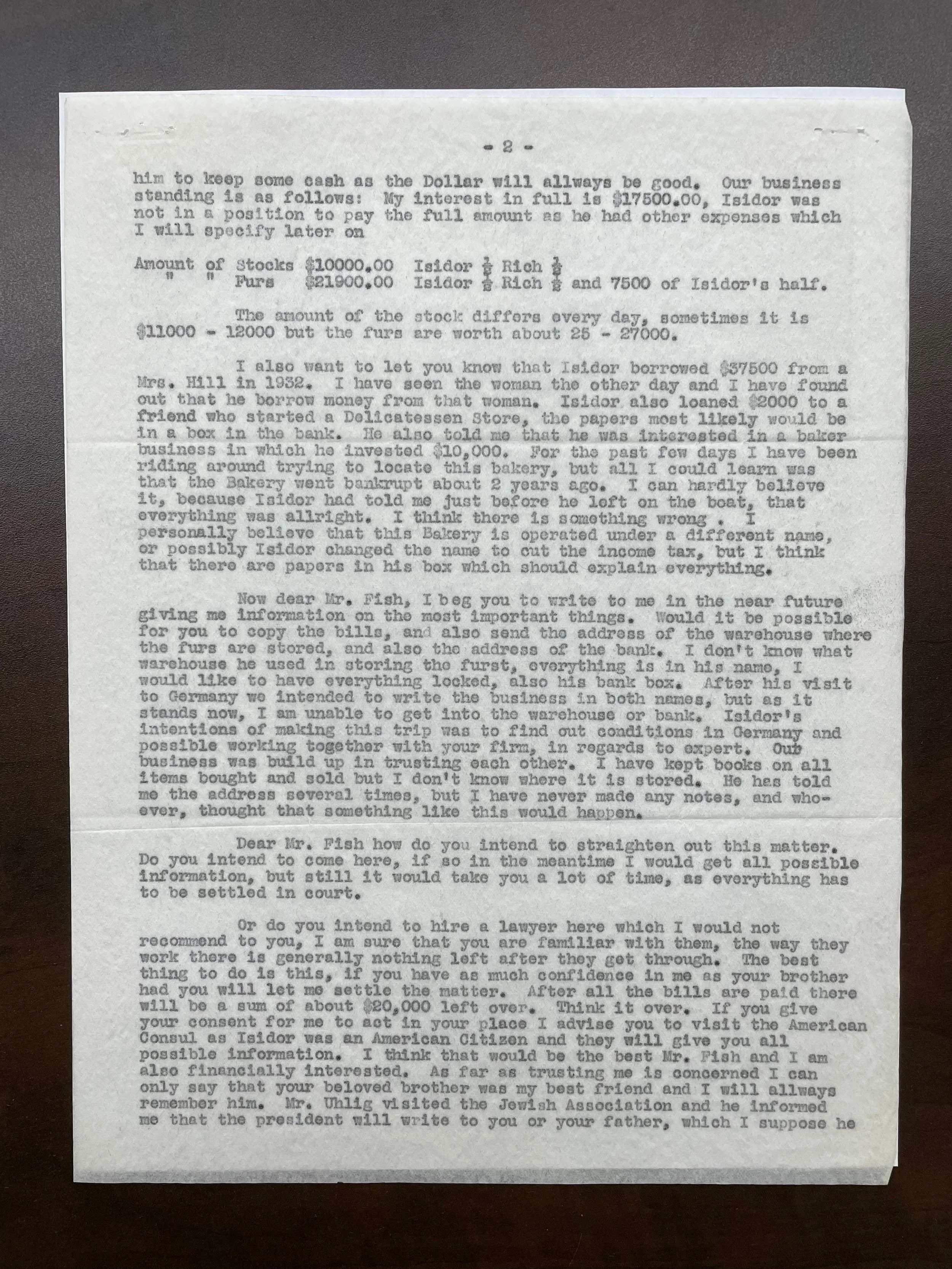

In 2019, City archivists Alex Hilton and Nathalie Belkin re-processed the papers and wrote a finding aid that provides a comprehensive list of materials in the series. While the files do contain a few photostat copies, most of the documents that might be considered “copies” are certified statements from other agencies attesting to Bruno Hauptmann or his associates and are revealing of the detectives’ investigative process. Of particular interest is the amount of material related to one of the mystery men in the case, Isidor Fisch. An associate of Hauptmann, Fisch returned to Germany and died of tuberculosis before Hauptmann’s arrest. Tellingly, he applied for a passport the day the dead baby was discovered.

Statement of Bruno Hauptmann taken at Bronx DA’s office, September 26, 1934. Lindbergh baby kidnapping closed case files, Bronx County District Attorney, NYC Municipal Archives.

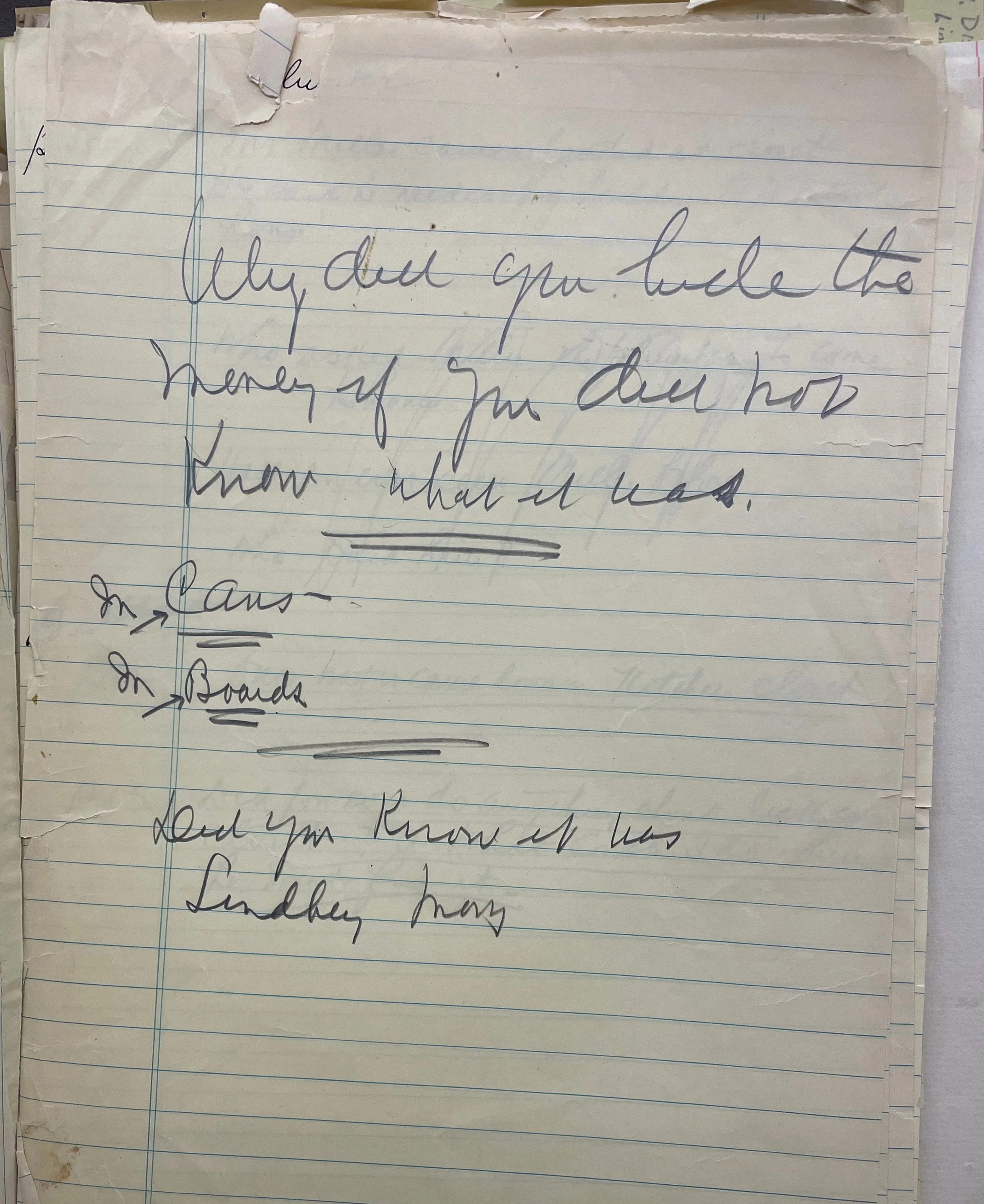

Note from detective or DA: “Why did you hide the money if you did not know what it was? In cans, in boards… Did you know it was Lindbergh money?” Lindbergh baby kidnapping closed case files, Bronx County District Attorney, NYC Municipal Archives.

Most of the official investigators agreed that that Hauptmann had accomplices, but there has been disagreement as to whether the mysterious “John” who met with Dr. Condon was Hauptmann himself. Witnesses at the Cemetery said he resembled Hauptmann, but it could have been Fisch, or another friend of Hauptmann’s who went by the name of John. Under interrogation, Hauptmann stated he was holding the ransom money for Fisch but could not offer a good explanation for why he had hidden it. As the detective scribbled in his notes, “Why did you hide the money if you did not know what it was?” Hauptmann claimed he and Fisch were in business together and produced correspondence to prove a fiscal relationship. Investigators believed these may have been part of scheme to launder the ransom money. They concluded that the money found at Hauptmann’s premises, plus the currency traced through Hauptmann’s records and investments over the prior three years totaled just over $50,000.

NYPD_17576b: Kitchen at 1279 E 222nd St. where part of Lindbergh ransom money was found, September 21, 1934. Det. Dunn and Murphy, alien squad detectives on case. NYPD photo unit collection, NYC Municipal Archives. Investigators said they found Dr. Condon’s phone number scribbled on the door of the pantry.

Memo regarding doctor who treated Hauptmann for a leg injury in 1933. Lindbergh baby kidnapping closed case files, Bronx County District Attorney, NYC Municipal Archives.

Another interesting document in the collection is an affidavit from a doctor stating that Hauptmann had been treated in his office for an old leg injury consistent with a fall from a ladder. There is also Hauptmann’s employer stating that he had quit his job the day after the ransom was paid. Another affidavit, from a man who had worked with Hauptmann on carpentry jobs, states that Hauptmann was often coming up with criminal “get-rich-quick” schemes that involved robberies or holdups, and in one case a kidnapping.

Newspaper clipping regarding tracing the $50,000 ransom. Lindbergh baby kidnapping closed case files, Bronx County District Attorney, NYC Municipal Archives.

In the end, the evidence, while largely circumstantial, was overwhelming and although Hauptmann professed his innocence to the end, the jury convicted him on February 13, 1935, and he was sentenced to death. Governor Hoffman of New Jersey, a German-American who publicly stated the case was a result of anti-German sentiment, stayed the execution several times. Finally, the judgment was carried out fourteen months later, on April 3, 1936. No other accomplices were ever brought to trial. Hauptmann’s widow Anna continued to profess her husband’s innocence and fought to clear his name until her death in 1994. She may have had other reasons than belief in his innocence. At the very least, she may have been an accomplice after the fact (the IRS had brought a tax fraud case against Bruno Hauptmann and her for failing to claim the $50,000 ransom money as income). Still further, by the time of his arrest, Bruno and Anna had a child, a boy about the same age as the Lindbergh baby was when kidnapped. Perhaps they couldn’t bear to have their child grow up thinking his father was capable of such a thing.

NYPD_17576e: Premises at 1279 E 222nd St. where part of Lindbergh ransom money was found, September 21, 1934. Det. Dunn and Murphy, alien squad detectives on case. NYPD photo unit collection, NYC Municipal Archives. At the time of his arrest Hauptmann had a child about the same age as the Lindbergh baby had been.

As for the Lindberghs, they fled the country to escape media attention from the case, spending 1935 to 1939 in England. During a trip to Germany Col. Lindbergh damaged his name by praising Hitler and the German air force, the Luftwaffe. He returned to the US in 1939 where he became involved in the America First movement, which advocated for keeping America out of the European conflict. His views on race and eugenics, and his early support for Hitler, are some of the reasons given by those who think he was somehow involved in the kidnapping of his own child. But bad things can also happen to bad people. In recognition of their critical participation in the investigation, the DOI, now rebranded as the FBI, was given jurisdiction over all future kidnapping cases. It was an early win for the young head of the organization, J. Edgar Hoover, a complicated man who would also become a controversial figure in American history.

Radiogram received from Dresden regarding Bruno Hauptmann’s criminal record in Germany, September 29, 1934. Lindbergh baby kidnapping closed case files, Bronx County District Attorney, NYC Municipal Archives.

Letter from the American Consulate in Leipzig, Germany to Chief Inspector John Sullivan regarding Isidore Fisch, October 1, 1934. Lindbergh baby kidnapping closed case files, Bronx County District Attorney, NYC Municipal Archives.

Copy of Hauptmann’s 1923 immigration investigation conducted on Ellis Island. Lindbergh baby kidnapping closed case files, Bronx County District Attorney, NYC Municipal Archives.

Letter from Hauptmann to the brother of Isidor Fisch. Lindbergh baby kidnapping closed case files, Bronx County District Attorney, NYC Municipal Archives.

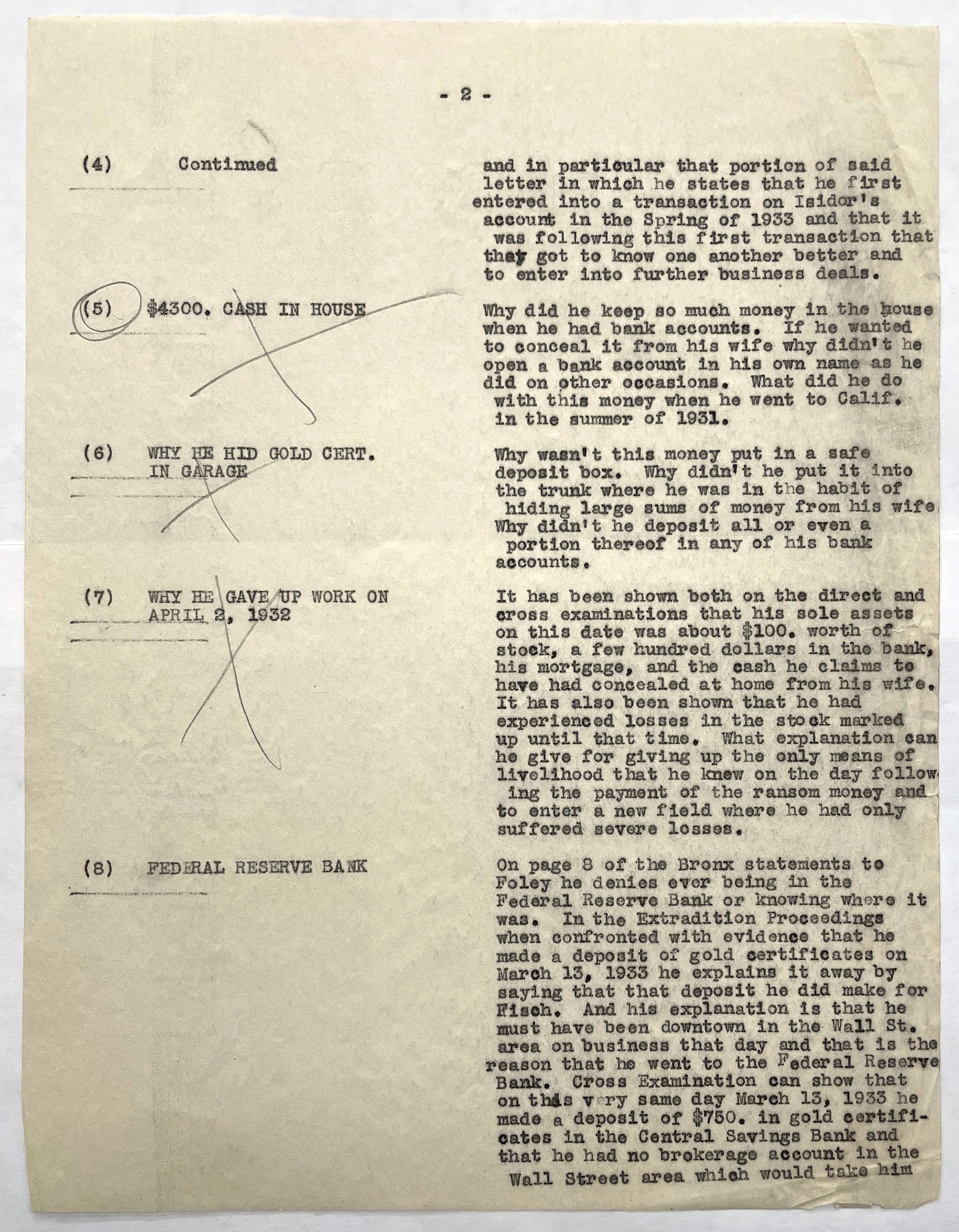

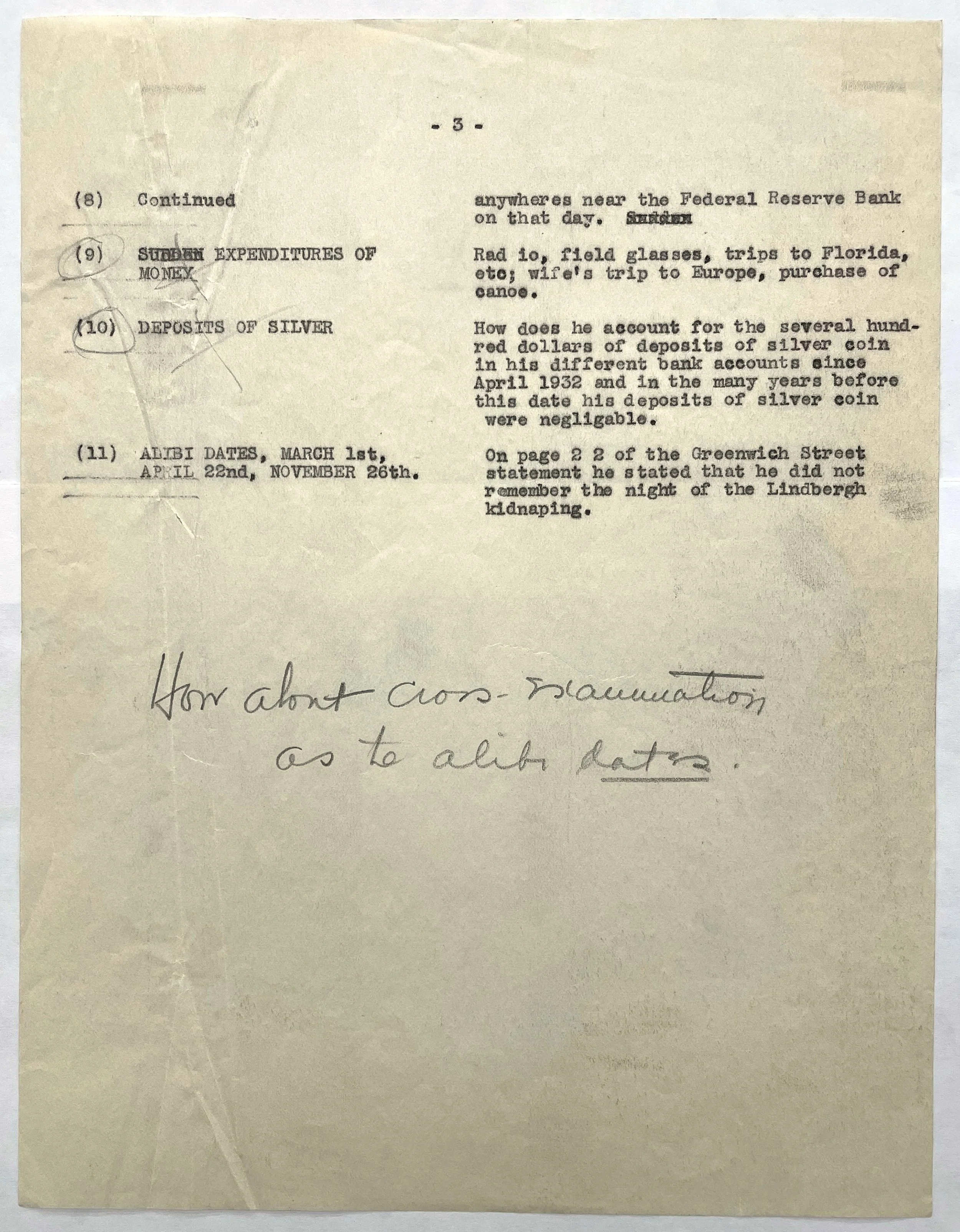

Notes from the Bronx DA. Lindbergh baby kidnapping closed case files, Bronx County District Attorney, NYC Municipal Archives.