The story of the tragic sinking of the ocean liner Titanic in April 1912 has been of enduring fascination in popular movies, books, documentaries, and more recently, a traveling exhibition of artifacts salvaged from the wreck. Less well-known is how New Yorkers immediately and generously aided survivors of that terrible tragedy.

Telegram to Mayor William J. Gaynor from former President Theodore Roosevelt, April 18, 1912. Mayor Gaynor Subject Files-Titanic Disaster-Expressions of Sympathy-roll 10, NYC Municipal Archives.

During the night of April 14-15, the ‘unsinkable’ luxury liner Titanic, on its maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York City, crashed into an iceberg in the North Atlantic. More than 1,500 of the 2,200 passengers lost their lives.

On April 17, one day before the rescue ship Carpathia, carrying 700 Titanic survivors arrived in New York, Mayor William J. Gaynor mobilized city government to accept donations from those who wanted to help.

Statement form Mayor William J. Gaynor concerning the relief for Titanic survivors, April 17, 1912. Mayor Gaynor Subject Files-Titanic Disaster Relief Fund-roll 10, NYC Municipal Archives.

Gaynor designated the Emergency Committee of the American National Red Cross to receive and disperse the donated funds. In two days more than $23,000 had been received for the relief effort, and by the end of April, donations topped $120,000 [about $350,000 in 2018 dollars]. The largest gift to the fund was $10,000 sent by Vincent Astor, in memory of his father John Jacob Astor IV. Many decades later, Vincent's widow and noted philanthropist, Mrs. Brooke Astor, would visit the Municipal Archives and donate $25,000 to the Brooklyn Bridge drawings project.

Letter from Percy Straus to Mayor William J. Gaynor, April 22, 1912. Percy Straus was the brother of Isidor Straus, who died on the Titanic. Mayor Gaynor Subject Files-Contributions and Acknowledgements – S, roll 11, NYC Municipal Archives.

Among the other casualties were prominent New Yorkers Ida and Isidor Straus, an officer at the R. H. Macy and Abraham and Straus department stores. Heeding Titanic crew member instructions allowing only “women and children” in the lifeboats, Mr. Straus refused to climb aboard and Mrs. Straus insisted on remaining on the doomed ship to be with her husband of 41 years. Adding to the tragedy of that night, many of the lifeboats launched only partly-filled. In June 1912, to honor the memory of Isidor and Ida Straus, the City named a triangle near their residence at Broadway and 106th Street, Manhattan, as Straus Park. On April 15, 1915, on the third anniversary of their deaths, the City dedicated The Straus Memorial fountain in the park, in which the bronze figure of Memory reclines in contemplation. Another memorial dedicated to the memory of the Titanic is a 60-foot lighthouse located at the corner of Water and Fulton Streets. It had been originally installed on the roof of the Seamen’s Church Institute at 25 South Street until 1968 when the building was demolished.

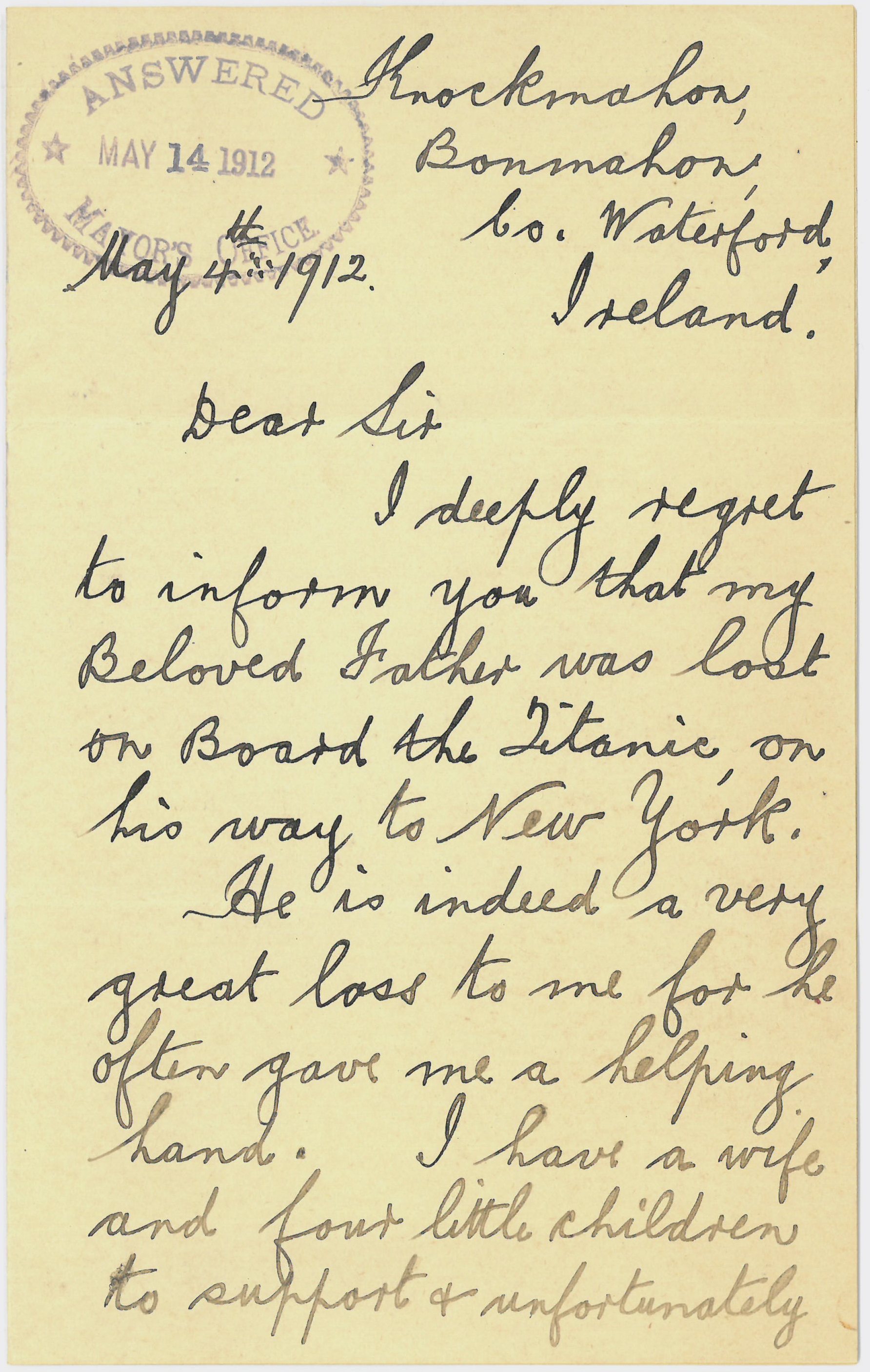

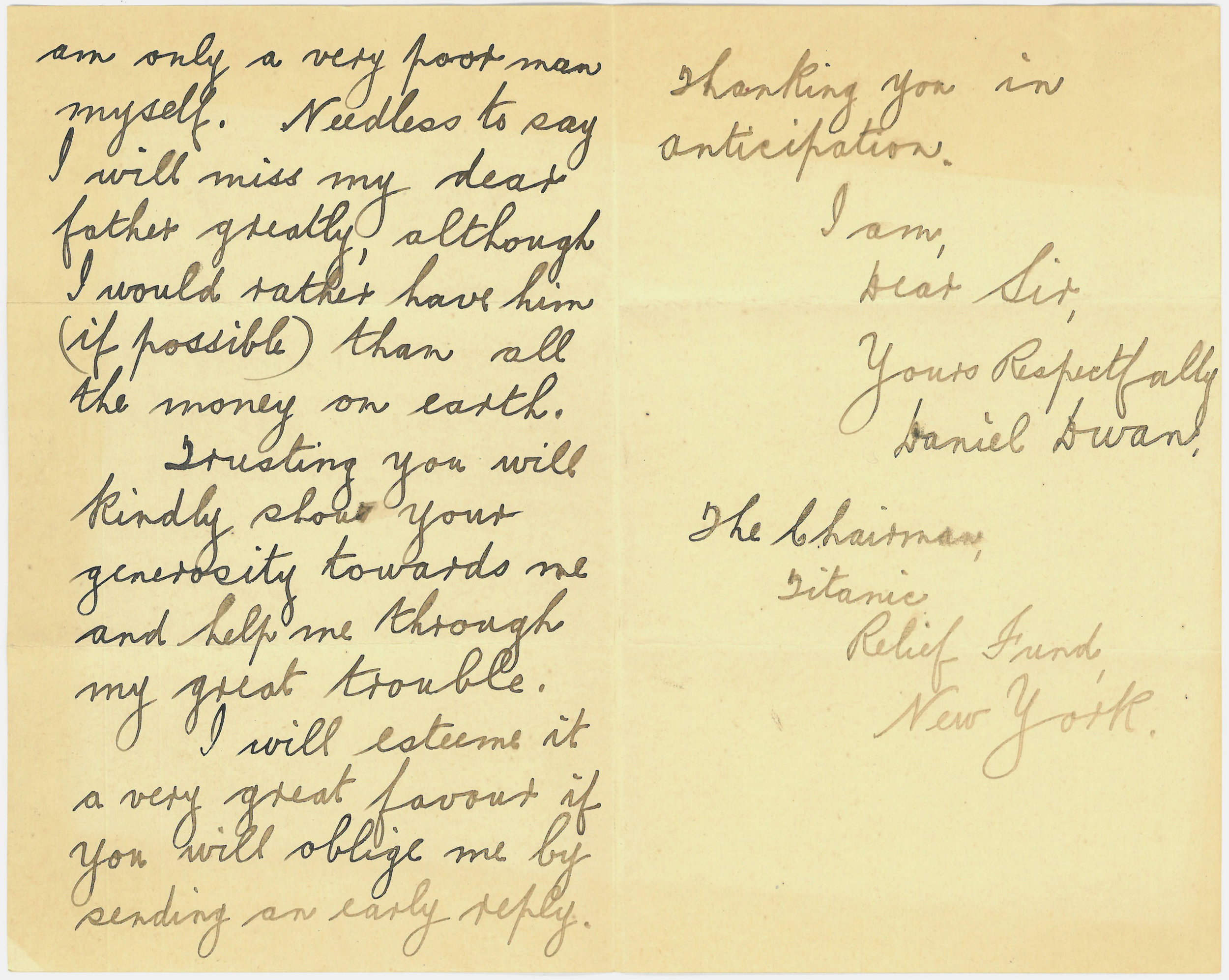

Mayor Gaynor's subject files on the Titanic Disaster Relief Fund include poignant letters asking for assistance. Daniel Dwan from County Waterford, Ireland, lost his father, and his father’s financial support, in the sinking. Newspaper accounts of the Emergency Committee’s work noted that assistance had been “….especially necessary for the families of widows.” [New York Times, “How Titanic Fund is Being Disbursed,” June 3, 1912]. Another Times article recounted the story of an English stone cutter who lost his tools when the Titanic went down. The fund awarded him $75. to replace the tools and noted he was destined to make a “mighty good American citizen.” [$121,611 is Raised for Mayor’s Fund, April 26, 1912.]

Chelsea Pier Plan 2358, Warren and Wetmore, 1908. Ports & Trade Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Construction of the Chelsea Piers is well-documented in the Archives’ Department of Docks & Ferries glass-plate negative collection. View along 12th Avenue, ca. 1908.

Had the Titanic reached its intended destination, it would have docked at Pier 59, one of the new piers in the Chelsea Section, along the Hudson River, at 18th Street. Maritime activities had been an important part of New York City’s economy since Colonial days, but by the latter half of the 19th century its piers were dilapidated. City merchants and political leaders feared loss of maritime business (and essential revenue) to rival East Coast port cities. After consolidation in 1898, the City embarked on an ambitious program to improve its waterfront infrastructure. Plans included construction of a nine 800-foot docks along the Chelsea waterfront between Little West 12th and 22nd Streets. The firm of Warren and Wetmore (architects of Grand Central Terminal) designed the reinforced concrete and pink granite pier shed facades in a handsome ‘Beaux-Arts’ style.

On April 18, 1912, the rescue vessel, S.S. Carpathia, with the Titanic’s survivors arrived at Cunard's Pier 54 at West 13th Street. The Carpathia had been 58 miles away from the Titanic when it received the distress signal. Arriving an hour after the Titanic sank, the crew rescued 705 passengers from the lifeboats.

In an expression of his continuing concern for the survivors of the Titanic sinking, Mayor Gaynor coordinated with the NYPD to prevent press photographers from interfering with the “unfortunate people,” aboard the rescue ship. Almost one hundred years later, New Yorkers would once again demonstrate their generosity after another terrible tragedy—the attack on the World Trade Center towers, on September 11, 2001. Future blogs will highlight the Archives’ collection of 9/11 materials.

S.S. Carpathia docked at Chelsea Piers, 1912. While we cannot be sure, archivists suspect this photograph was probably taken after the Carpathia arrived with survivors of the Titanic disaster. Department of Docks & Ferries collection, #697, NYC Municipal Archives.