This week, For the Record highlights two exceptional opportunities to experience innovative interpretations of archival material. Both make use of historical New York Police Department (NYPD) surveillance films from the Municipal Archives collection.

The first is the annual Photoville festival where the Municipal Archives has debuted “NYC Undercover: Post-War Sound and Vision from NYPD Surveillance and WNYC Radio” a film exhibit combining historic NYPD silent surveillance films from the 1960s and 70s, with vintage WNYC radio broadcasts.

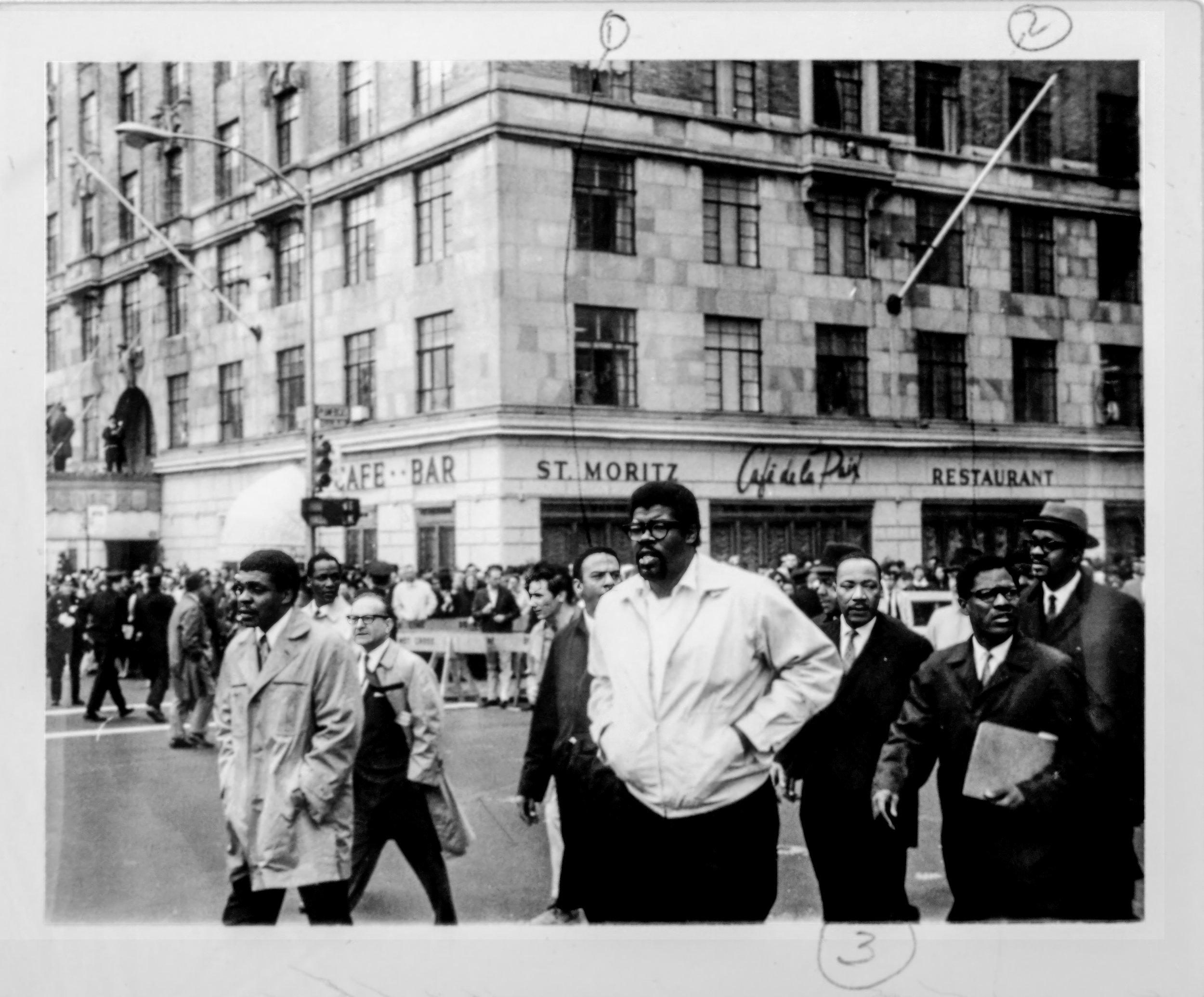

Spring Mobilization Committee March, April 15, 1967. NYPD Special Investigations Collection, NYC Municipal Archives. The Spring Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam (later called the National Mobilization Committee) organized some of the first large-scale protests of the war in 1967.

DORIS archivist Chris Nicols created NYC Undercover using video from various events and WNYC radio broadcasts. The end results include ticker-tape parades for the Gemini III and Apollo 11 astronauts paired with an interview with legendary baseball player Jackie Robinson, who expressed his view that the astronauts were heroes, as well as an NAACP and Congress for Racial Equality protest in Southeast Queens matched with audio from Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s speech to the City Council after winning the Nobel Prize, and more.

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (third from right), Andrew Young (1), Bernard Scott Lee (2) and other supporters in the Spring Mobilization march near the Hotel St. Moritz, Central Park South and 6th Avenue, April 15, 1967. NYPD Special Investigations Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

The NYPD surveillance films had been originally created by the Bureau of Special Services and Investigations (BOSSI) between 1960 and 1980. During their heyday in the 1960s and 1970s, BOSSI gathered information on individuals and groups arrayed along the political spectrum, but particularly civil rights, anti-war and feminist activists.

Nicols selected the audio from the Archives’ collection of broadcasts recorded by the municipal radio station, WNYC. Launched in 1924, reporters from the city-owned station turned up at events for more than seven decades, recording everyone from news announcers, musicians, and celebrities, athletes, poets and politicians. In 1996 the radio station was sold by the City to the nonprofit WNYC Foundation and it will celebrate its centennial next year.

Earth Day, Union Square, April 22, 1970. NYPD Special Investigations Collection, NYC Municipal Archives. Earth Day celebrations in Union Square Park included cleanup crews composed of school children and community members. Con Edison, often criticized for their environmental policies, donated brooms, mops, and other supplies for the cause. Other events in the park included Frisbee games and a massive plastic bubble filled with “fresh air.”

NYC Undercover will be on display through Sunday, June 18 at the Emily Warren Roebling Plaza in Brooklyn Bridge Park, from 12-6 p.m. Tuesday through Thursday and 12-8 p.m. Friday through Sunday. For more information, visit https://photoville.nyc.

The second opportunity also makes use of historic NYPD surveillance films. On June 16, 2023, Department of Records and Information Services’ Public Artist in Residence, Kameron Neal, will debut Down the Barrel (Of A Lens). The screening will take place at the Brooklyn Army Terminal’s Annex Building. The program is free and will run from June 16, through June 18, 2023. More information and RSVP is available here.

During Neal’s residency at DORIS he examined the digitized NYPD surveillance footage from the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. As noted above, the films capture a turbulent time in the City’s history. Mostly shot by plainclothes officers from 1960-1980, Neal’s interpretation focuses on a constellation of moments in the film collection when people stopped to look back directly into the camera lens; acknowledging they were being surveilled.

Columbia students climb a barricade during protest, May 21, 1968. NYPD Photo Collection, NYC Municipal Archives. In the Spring of 1968, student protests broke out at Columbia over links with the Department of Defense and plans to build a gymnasium in Morningside Park. Students occupied several buildings.

Designed as a two-channel film installation, one channel contains footage of civilians looking directly into the camera, while the other creates an abstracted portrait of the NYPD through jittery shots of their shadows, trench coats, and shoes. The two channels face one another as a symbolic reimagining of these police encounters.

The Public Artist in Residence (PAIR) program is a municipal residency run by the Department of Cultural Affairs that embeds artists in city government to propose and implement creative solutions to pressing civic challenges.

While both exhibits use some of the same film, the resulting projects are vastly different and illustrate how these rich collections can be used in creative pursuits.