Question: What was once ubiquitous in New York City and now almost completely absent from the streetscape? Answer: The Horse.

New York Central and Hudson River Railroad Company’s Freight Depot at West and Barclay Streets, Manhattan, November 1910. Department of Docks & Ferries Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Horses arrived with the first European colonial settlers and for the next three centuries powered the city’s transportation, construction, law enforcement, firefighting, street cleaning, ambulance, and delivery services. With related occupations and businesses—saddlers, blacksmiths, carriage manufacturers, harness makers, feed suppliers, stables, auction houses, etc. the City was dense with horses. This week, For the Record introduces the topic and features pictures selected from the Municipal Archives gallery that illustrate the preponderance of the horse in city life. Future articles will identify and explore resources in the Archives for further study of the horse in the City.

Team of 34 horses bringing steel girders for Municipal Building from dock at Battery Place, February 26, 1911. Photograph by Eugene de Salignac, Department of Bridges, Plant & Structures Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

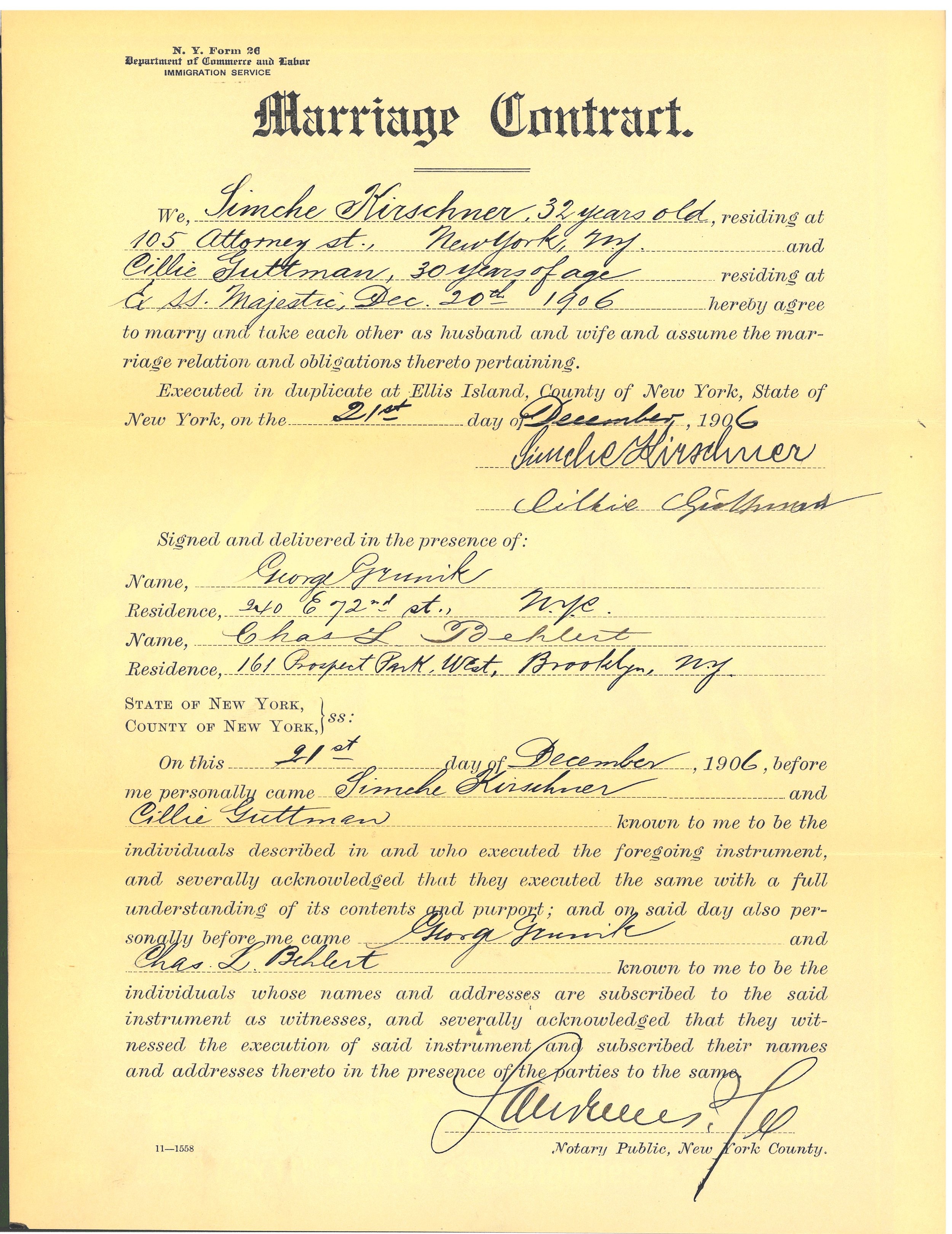

The Dutch brought horses to New Amsterdam to carry heavy loads and operate gristmills and sawmills. English settlers imported horses for racing. Soon after their arrival, references to horses appear in official records, most often as the subject of assorted regulations and taxation. An entry from The Minutes of the Common Council for October 15, 1670, provides a typical citation: “Ordered that all and every person that should ship from this place any horses, mares or geldings to Virginia, Maryland or any other outward plantations should pay for every horse, mare or gelding one shilling in silver or two guilders in wampum....”

Subsequent records document regulations about where and how horses could be bought and sold, watered and fed. And many rules focused on horse racing—most often the prevention thereof.

Police officer with his horse in Central Park, ca. 1915. NYPD Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Department of Street Cleaning snow removal team, n.d. Department of Sanitation Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

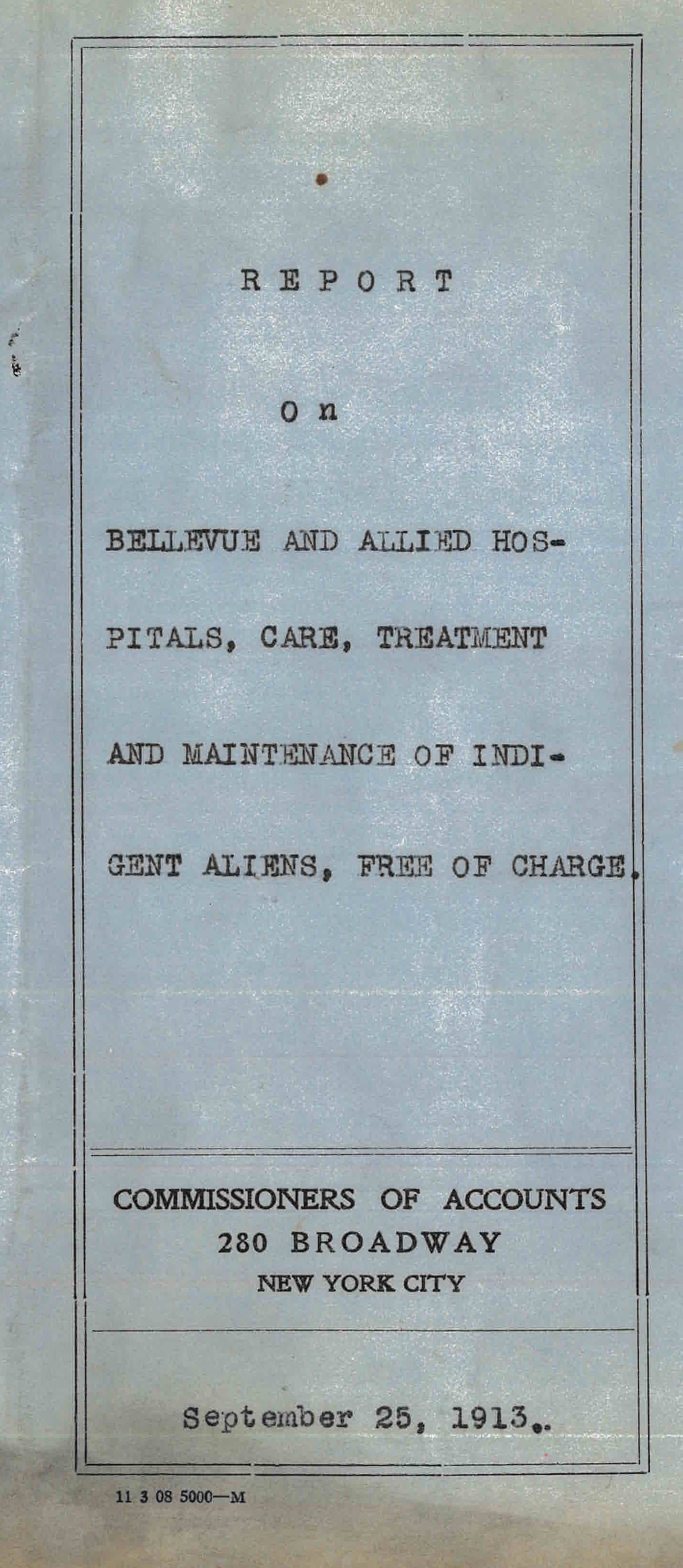

The first horse-drawn omnibus in the nation operated along Broadway in Manhattan from Prince to 14th Street beginning in 1832. Horse-drawn passenger vehicles continued to ply city streets until 1918. Beginning in the 1860s, fire companies adopted horses to pull fire-fighting apparatus. Similarly, the Street Cleaning Department, and the Department of Public Charities and Hospitals hitched horses to their equipment.

The number of plans related to features of Central Park specifically dedicated to horses in the Department of Parks drawing collection points to their importance for leisure activities.

Central Park, shelter for carriages and horses, preliminary study, front elevation. Jacob Wrey Mould, 1871. Department of Parks & Recreation Drawings Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Horse Aid Society, Manhattan Bridge, October 18, 1917. Photographer: Eugene de Salignac. Department of Bridges Plant & Structures Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

West 44th Street, September 6, 1931. Photographer: Frank Savastano. Borough President Manhattan Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Other records reveal another consequence of the city’s reliance on horses. There are disturbing numbers of arraignments in the Police and Magistrate’s Court docket books for offenses related to animal abuse. In many cases, the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) brought the charges. New York City’s branch of the ASPCA, founded in 1866, was the first in the U.S. based on a similar group that originated in Great Britain. More recently, the ASPCA monitors conditions of the City’s carriage horses.

By the early twentieth century, the number of horses in the city began to diminish. Technology, in the form of motor vehicles—cars and trucks, gradually reduced the city’s reliance on horsepower. Between 1910 and 1920, the number of horses in the City declined from 128,000 to 56,000.

Riders on Central Park Bridle Paths, June 1937. Photographer: E.M. Bofinger. WPA Federal Writers’ Project Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Although much reduced in number, the horse is not entirely absent from the City scene today. Aqueduct Racetrack in Queens, the only racetrack located within New York City limits, continues to operate, generally from late October through April. Closure of the Claremont Riding Stables on Manhattan’s Upper West Side in 2007 greatly reduced, but did not entirely eliminate people enjoying horseback rides along Central Park’s bridle paths. And despite decades-long protests and controversy, horse-drawn carriages still meander through the southern portion of the park.

Highway maintenance, Queens Boulevard and Woodhaven Avenue, August 13, 1926. Borough President Queens Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Coney Island Hospital ambulance, n.d. Department of Public Charities and Hospitals Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Department of Street Cleaning rubbish wagon, Brooklyn, n.d. Department of Sanitation Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Teamster on West Street, Manhattan, February 10, 1938. WPA Federal Writers’ Project Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Horse with feed bag, ca. 1936. WPA Federal Writers’ Project Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Village blacksmith, 33 Cornelia Street, Manhattan, August 6, 1937. Photographer: E.M. Bofinger. WPA Federal Writers’ Project Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Mayor Edward Koch at the Big Apple Stakes, Aqueduct Racetrack, Queens, April 26, 1980. Mayor Edward Koch Photograph Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.