New York City’s Municipal Reference Library initially opened to the public at 280 Broadway on March 31, 1913, with a dedication ceremony attended by many municipal officials. A small booklet commemorating the event was recently located on the shelves of the current Library at 31 Chambers Street.

Cover page of Municipal Reference Library, 1913. NYC Municipal Library.

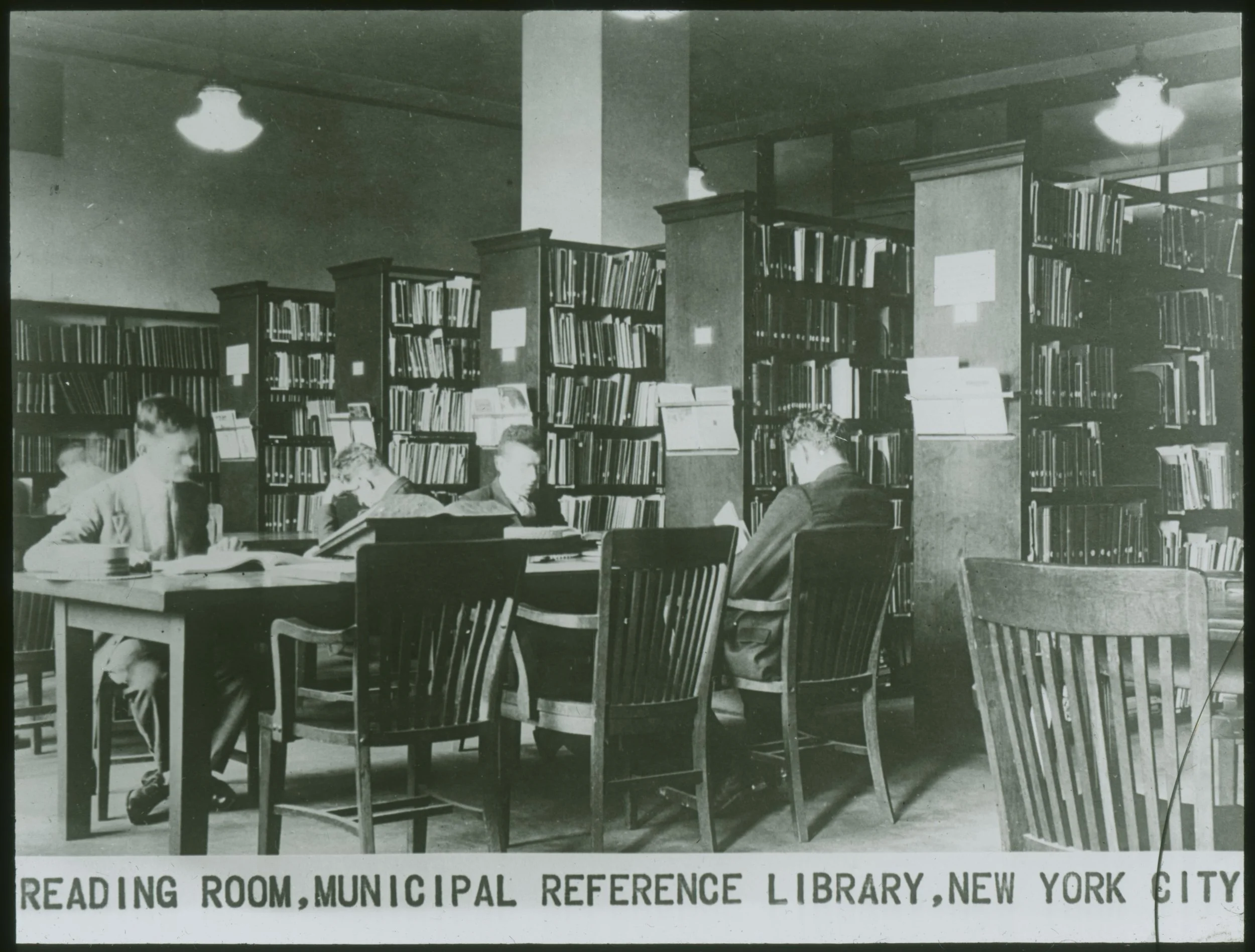

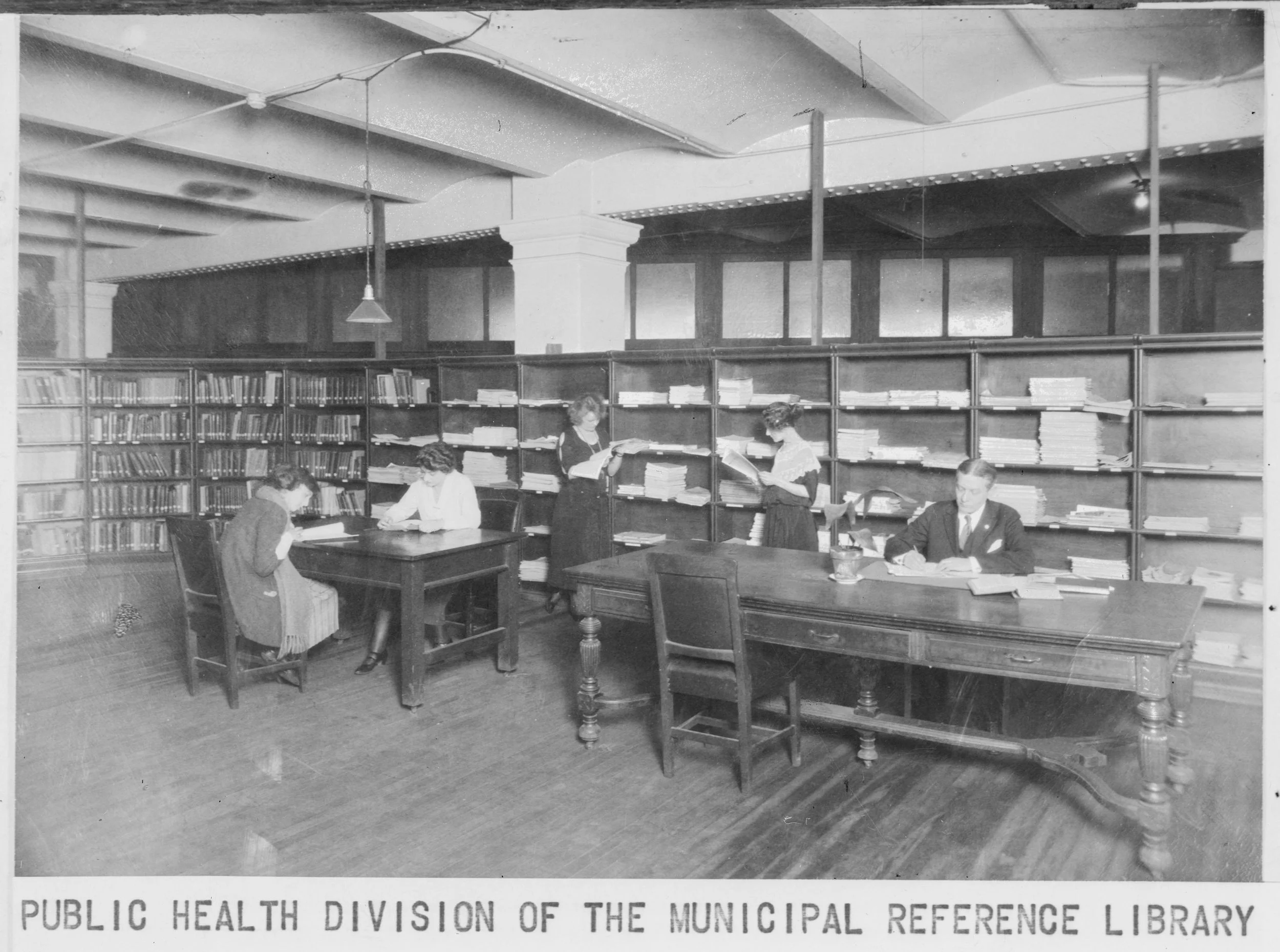

All texts from glass lantern slides, ca. 1930. Municipal Library Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Noting that the library contained over 5,000 books and pamphlets, “Out of the 5,000 books, only 368 were actually purchased for the library. The others were contributed by the Comptroller from the shelves of the libraries in the Department of Finance. This was possible because the department had been engaged for some time in gathering books of the kind most suitable to a municipal reference library.”

Long a goal of City Comptroller William Prendergast, the Library was one of the many new institutions proposed by reformers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This period, the Progressive Era, was a period of widespread activity to reform institutions, both public and private. Movements to improve conditions for workers and immigrants led to the development of labor unions and settlement houses. Efforts to reduce government corruption focused on government efficiency including the introduction of business practices into government and establishing criteria-based hiring practices to reduce patronage in employment. Municipal libraries fit into this by providing government decisionmakers with studies and statistics about government operations so decisions might be fact-based.

Reading Room, Municipal Reference Library, New York City, ca. 1930. Municipal Library Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

New York was not the first municipality to open a library with a focus on government efficiency. In 1908, the National Municipal League, a reform-minded organization promoting civic engagement, proposed that local governments establish municipal libraries. Several cities took up the charge: St. Louis, Baltimore, Kansas City, Milwaukee and Minneapolis all established libraries before New York. In his opening address, Prendergast acknowledged this and said, “No city has as great municipal problems as those which confront New York, and consequently New York should be in the vanguard of those communities that are quick to recognize the utility of such an institution.”

The Municipal Reference Library maintained a separate Public Health Division at the Department of Health, ca. 1930. Municipal Library Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Prendergast, a Republican, ran unsuccessfully for Congress before being elected as the City’s Comptroller in 1909, and re-elected in 1913. An online search shows that he authored several publications about finances including: “The business of New York City: how the city gets its money and how it spends it” and “Report on the Tax Levies of the City of New York.” The Municipal Library Catalog includes these publications and thirty more on topics ranging from west side improvements, centralizing city purchases, street improvements and the telephone situation in municipal departments. All in all, he seems to fit the mold of a progressive-era reformer.

The library’s first home at 280 Broadway (then known as the Stewart Building and later as the home of the New York Sun newspaper) consisted of two rooms on the 4th floor. Getting that space was an achievement, described in the proceedings. Prendergast, Mayor John Purroy Mitchel and Manhattan Borough President George McAneny comprised the budget committee of the Board of Estimate in 1910 and proposed funding a Municipal Library. (Mitchel actually was the President of the Board of Aldermen but temporarily was a member of the Board of Estimate because he served as Acting Mayor for several months in 1910 when Mayor William Gaynor was recovering from an assassination attempt.) Regardless, his status did not help because the Board of Aldermen refused to appropriate the meager sum needed to fund the library.

Municipal Reference Library, New York City, ca. 1930. Municipal Library Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

As New York prepared for a municipal election in 1913 that would pit Tammany against reformers, the three elected officials determined that the library should be established before the end of Gaynor’s term. So, Comptroller Prendergast used funds allocated to his office to set up the library—$750 to purchase new books and $500 for the furniture. The librarian was also funded through the Department of Finance (then part of the Comptroller’s Office). As stated in the introduction: “The limited appropriations for the Department of Finance were not sufficient to provide entire equipment for the library. The library cases in the Bureau of Municipal Investigation and Statistics, of the Finance Department, were used for one of the rooms, and wooden shelves were erected in the other. It was necessary to buy a desk, some chairs and tables, but except for these and the 368 books already mentioned. The library was built up with equipment already owned by the Department.”

Files and Catalogue in the Municipal Reference Library, New York City, ca. 1930. Municipal Library Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Despite the obstacles, Prendergast seemed optimistic in his address at the opening. “This Municipal Reference Library should be a “fact centre.” To it, public officials public employees, civic organizations and citizens generally, should be able to appeal for information on any subject that may reasonably be considered within the domain of municipal performance. If the library should not happen to have adequate data relating to a subject regarding which inquiry is made, it will be the duty of those in charge to immediately secure the necessary information.”

Library of the Public Health Division of the Municipal Reference Library, ca. 1930. Municipal Library Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

He continued, “The functions of this library can be made very far reaching. They could include the making of investigations, the preparation of reports, the drafting of legislative bills and city ordinances, lecture courses and public discussions…. If facts are required they should be secured by the library, but the quest must be for facts. Any attempt to use it for personal or political advantage would destroy the value of the library as an element of municipal service.”

Page from the Municipal Reference Library, 1913. NYC Municipal Library.

Prendergast praised the assistance of the New York Public Library and support of the Brooklyn Public Library and envisioned a future with branches of the Municipal Reference Library in all of the boroughs, through partnerships with the library systems. This was not to be. He also recommended that the 8,000 volumes and 500 pamphlets in the Aldermanic Library be transferred to the Municipal Reference Library, which eventually did occur.

Mayor Gaynor, who would die from complications of the assassination attempt in September, paving the way for Mitchel to be elected the City’s youngest mayor on the Fusion ticket, then spoke. Praising the work of the Comptroller, and noting the modest beginning, he said, “It will grow, and grow rapidly, the object being to bring into one library all information and statistics, not only regarding our own city, but regarding all cities, and when I say all cities I mean the cities abroad as well as here. In that way much can be gathered together of the greatest value. It will be a place not only where those working in municipal government may go to get information, but it will be a place to which the writers on municipal topics may go. The future historian, Mr. Comptroller, will make use of it.”

Another speaker, the Reverend Thomas E. Murphy, Vice President of Brooklyn College, warned attendees that statistics were insufficient without people with open minds. “We have all had occasion to observe at times that figures and statistics, like presumed facts of history, may easily become an accumulation of things that are either not so or are not the expression of the whole truth. For instance, a certain class of undeniable facts and statistics about our city might give—should I not say, have given?—outsiders the false impression that this is the most immoral city in the world and that our police and other officials are a corrupt and inefficient band of public servants. Other instances might also be cited, if necessary, to convince us that no man needs breadth of view and an unbiased mind more than the student of statistics.”

By 1930, the Library had moved to the Municipal Building and its collection included more than 50,000 books. Fast forward 112 years from its founding and we see that the Municipal Library is well used. Historians, government officials, political scientists, students, city workers and more benefit from this reform. By 2025, the Library expanded to offer City agency reports online via the Government Publications Portal, official social media post and hosts the City’s centralized Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) portal.