Robert Moses, long known as the “Master Builder,” could also be remembered as the “Master Letter Writer.” Evidence of his communication style can be found in many Municipal Archives collections. Always clear and direct, to-the-point and often quite blunt, Moses seemed not concerned whether he was insulting or rude. His prolific communications have served as a bonanza for researchers investigating virtually any topic concerning twentieth-century New York City and more broadly U.S. urban history.

Graphic materials created during the Moses era are noted for their quality. City Planning Commission Report, 1940-1950, Mayor William O’Dwyer Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Two series accessioned from the Department of Parks contain the greatest volume of his correspondence: General Files, during the period when he served as Commissioner (1934-1960), and his records as a City Planning Commissioner (1940-1956).

Marine Park, Staten Island, Report to Mayor LaGuardia, 1940. City Planning Department Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

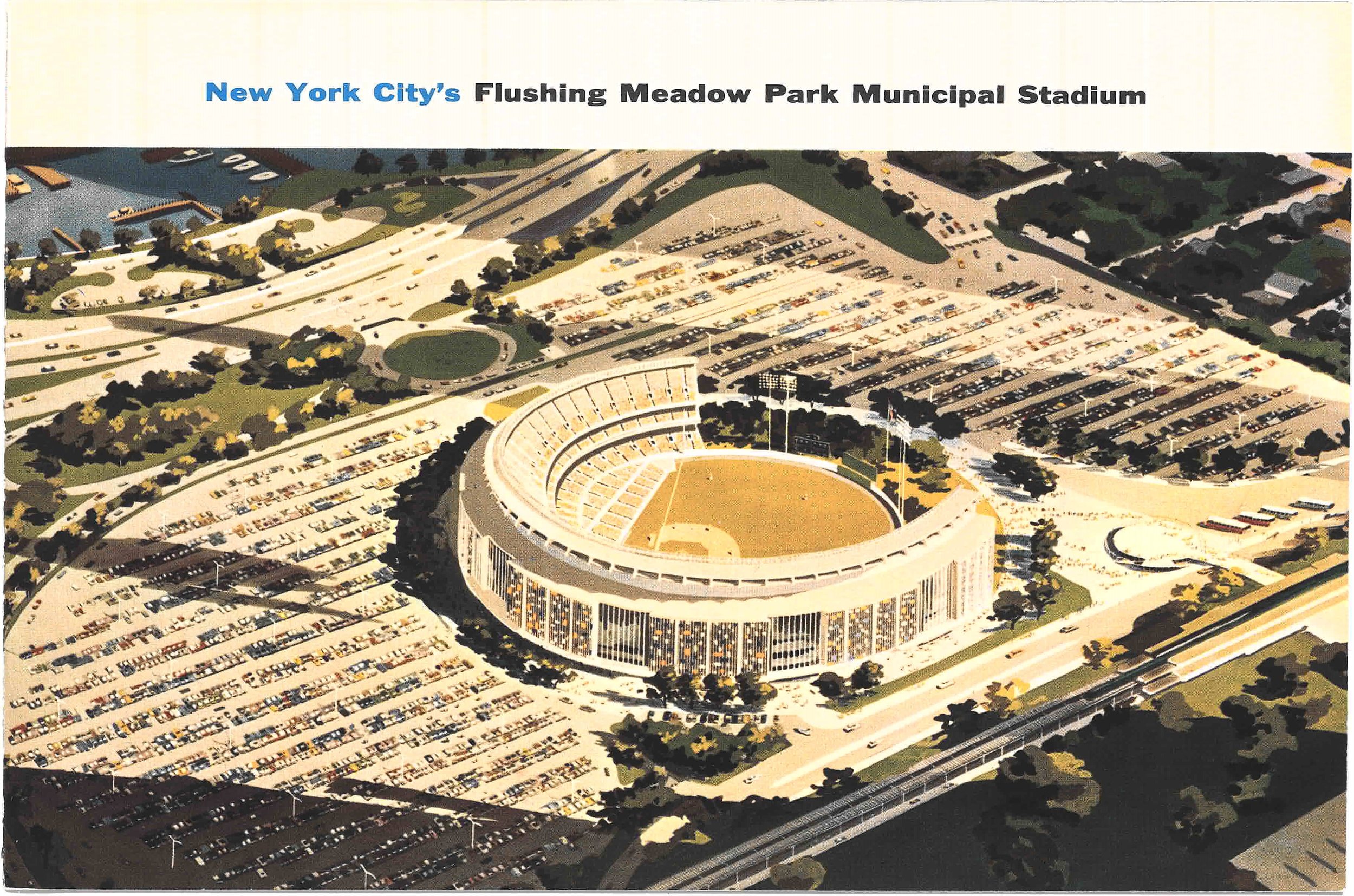

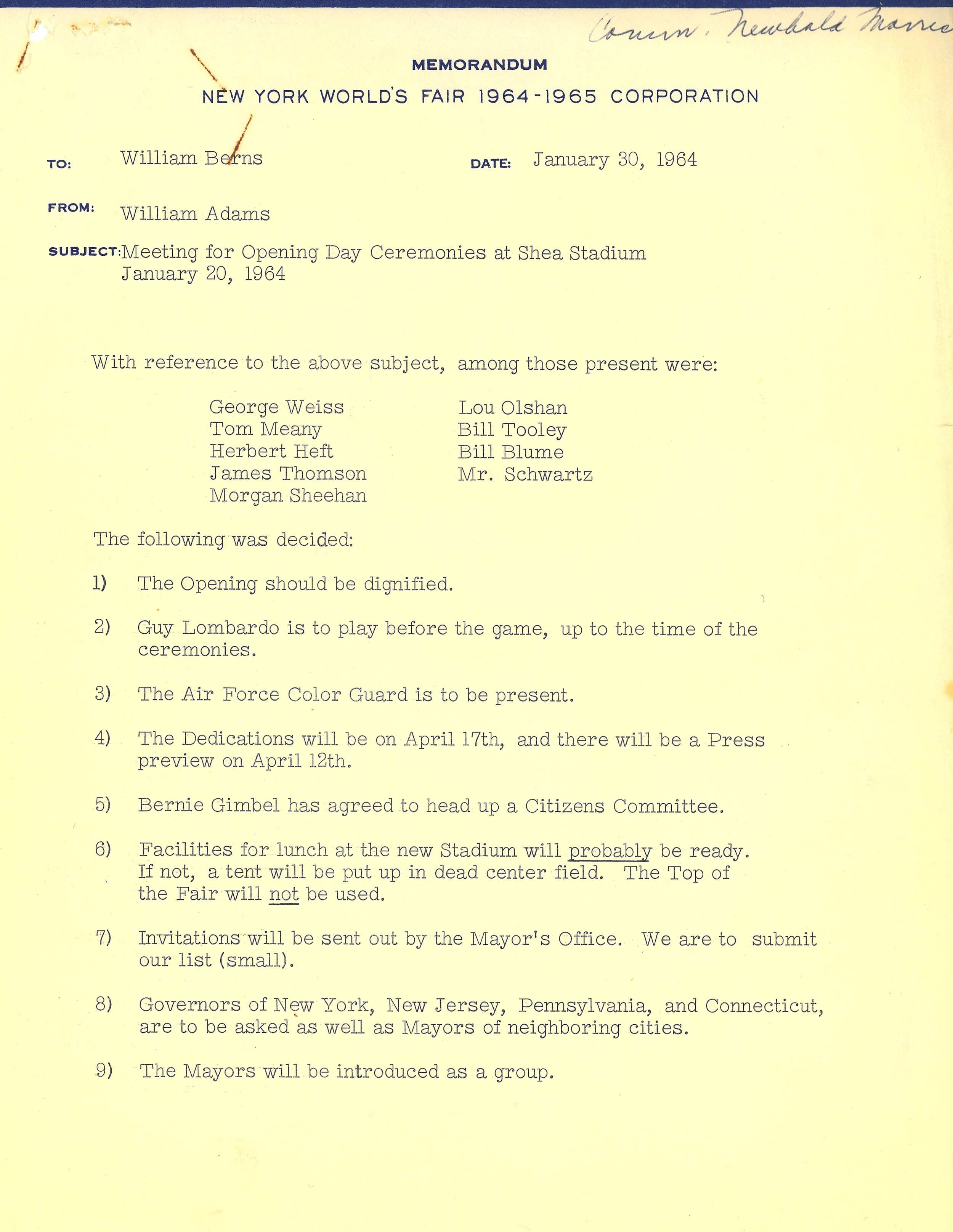

The bulk of the General Files records pertain to the agency’s daily operations. However, examining the intellectual content of this series shows that Moses also responded to a wide range of issues outside of the Park system. The files contain copies of letters written by him as Chairman of the Office of Committee on Slum Clearance and City Construction Coordinator. This material provides extensive documentation of his activities related to subjects such as highways, housing, and airports, as well as the 1964/65 World’s Fair.

In addition to the Parks-series, significant quantities of correspondence generated by Moses appear in the mayoral collections. From Mayor LaGuardia through Wagner, there are dozens of folders – in the Departmental series – e.g. Parks, City Construction Coordinator – and in the subject files, with letters from Moses.

Another notable feature of Robert Moses’ correspondence is its accessibility. His records are well-indexed. In the Parks series, for example, Moses, or more likely his secretary or possibly the filing clerk, assigned a subject to every document and placed it in labeled folders arranged alphabetically.

For the Record will let Moses take over from here:

1941 “Necessarily long and technical”

Moses included a cover letter written to Mayor LaGuardia (Moses usually addressed him as “Major”), dated October 30, 1941, as part of his printed report on “Construction and Restoration of Monuments, Memorial and Historic Buildings.” Never one to sugar-coat a subject, he informed LaGuardia “We have inherited from past administrations some God-awful monstrosities in the form of monuments. We are also the legatees of some very fine things.”

1938 “Exclusively for bicycle riders”

Robert Moses’ reputation for building a vast highway system catering to automobile transportation is well deserved. He began with the Southern State Parkway on Long Island in 1927 and ended with an extension to the fabled Long Island Expressway in 1972. And, in between, he constructed the Cross-Bronx Expressway, perhaps the most controversial urban highway built in America. So perhaps it is surprising to find this letter, dated May 20, 1938, informing Deputy Mayor Henry Curran that “In the meantime, and off the record, I am also arranging to open the Long Island Motor Parkway from its beginning at Nassau Boulevard to Alley Park as a bicycle path exclusively for bicycle riders.”

1957 “Hornswoggled”

A letter from Whitney North Seymour, President of the Municipal Art Society, on January 3, 1957, seems to have especially irked Mr. Moses: “I don’t know who invented the term “new slums” or what it means, and don’t propose to be hornswoggled into any such silly controversy.” He added, for good measure, “When, by the way, did the members of your Society stop beating their wives?”

1956 “Subject: Polo Grounds”

The imminent departure of the Giants National League baseball team from their stadium at the Polo Grounds was a huge concern. But as can be discerned from this letter to James Felt, Chairman of the City Planning Commission, Moses saw it as an opportunity to build more housing.

1954 “The Third Avenue EL”

Within a week after Mayor Robert Wagner took office in January 1954, Moses pressed him for a decision regarding demolition of the Third Avenue Elevated Railroad. As Moses explained, “It is obvious that completion of the Second Avenue Subway is a long way off.” “It may well be ten years.” Little did he know.

1957 “Looks rather foolish to us”

Moses’ reaction to an idea by the New York Central Railroad to build motels “on gratings” was not encouraging, “Doesn’t at first blush seem a very brilliant or profitable way of using railroad rights of way, even if there is a demand for cheap hotel accommodations.”

1938 “Henry Hudson did discover the Hudson River”

This correspondence to Henry Curran may have meant something to the Deputy Mayor, but otherwise seems opaque.

1943 “I say its Spinach”

Reporting to Mayor LaGuardia on a meeting about the Brooklyn Navy Yard, Moses took the opportunity to comment on social workers: “These people never get anywhere, and it is a waste of time to get excited about their plans.” Moses believed parks and playgrounds would solve all social ills and so concluded to the Mayor: “If I had the sense God gave geese, I would have insisted that the only thing worth accomplishing was to get rid of Raymond Street and substitute a playground.”

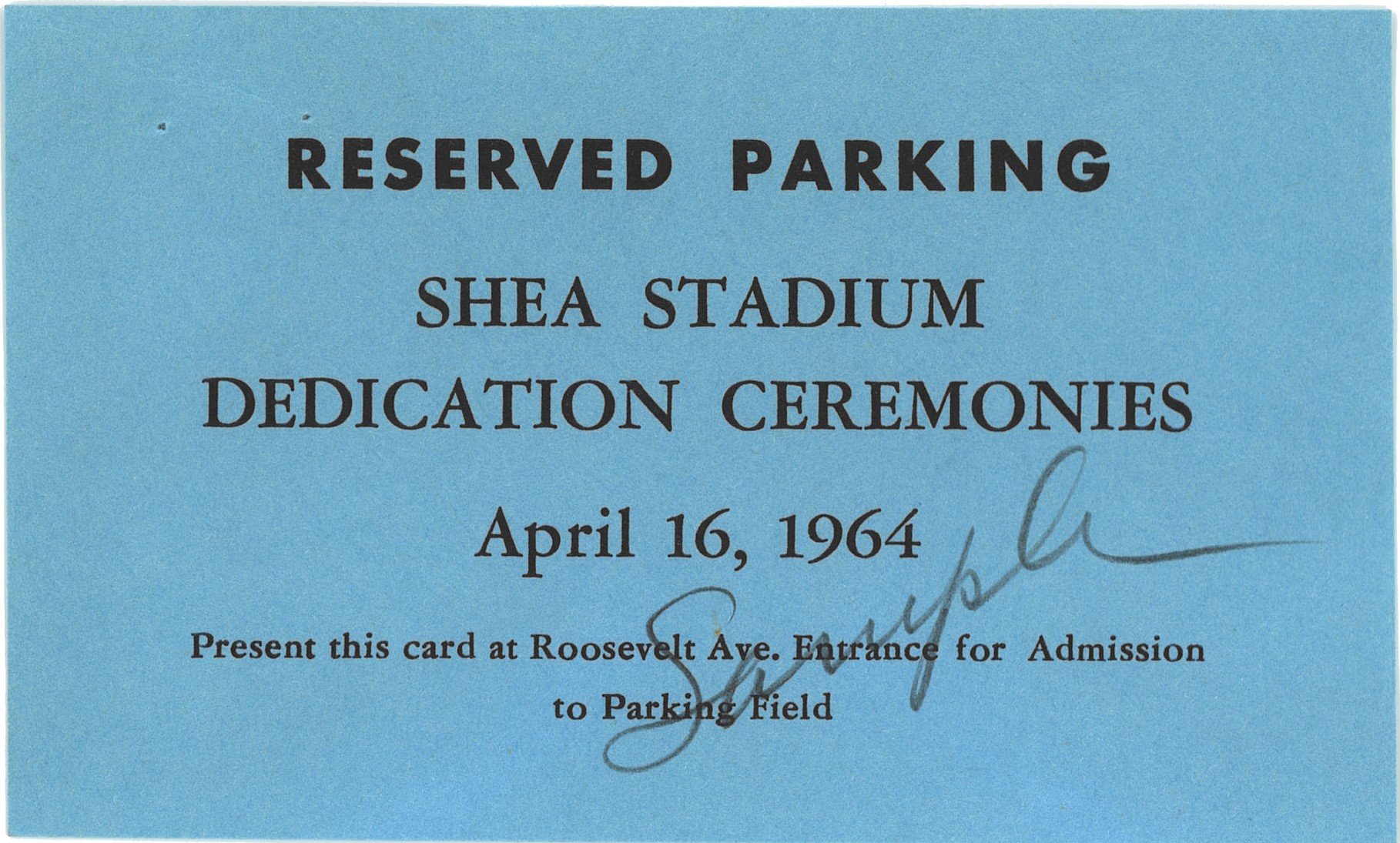

Several For the Record articles have highlighted the Robert Moses collections and/or his activities. From the Dank Recesses: The Department of Parks General Files provides some general background about the Parks collections. Documenting the New Deal, The Aerial Views of Robert Moses and most recently, We Shall All Be There: Dedicating Shea Stadium, also draw on Moses-related records.