Colonial era documentation related to Native Americans, like most, if not all the early collections, were created by Dutch West India Company. So, they are from a singular perspective and in some instances in a language that is no longer spoken. Scholars may still ruminate on the meanings of words or phrases in Old Dutch manuscripts. Early Dutch settlers were adamant about documenting any and all interactions. So, when a Native American agreed to a land deed with a mark that represented a signature, we can speculate about translations and interpretations of contracts. And further, understand the vital importance of individuals like the Sarah Kierstede who acted as a translator for the colony.

Still image, Longhouse. Mapping Early New York. Courtesy of the New Amsterdam History Center.

The Municipal Archives’ collection includes numerous examples of agreements between the indigenous peoples and the colonial settlers based on the European custom of formalizing contracts and other transactions with written documents.

Legal records and agreements are common throughout early colonial collections. Signatures or marks made by Native Americans are distinct from those of the settlers. The differences bring up important issues of language, interpretation, and understanding of cultural norms and traditions.

An Indian Village of the Manhattans prior to the occupation by the Dutch. D.T. Valentine. Courtesy of the Municipal Library, City of New York.

Native-American settlements usually included long houses and/or wigwams. These were so impressive that they were featured in the maps created by Adriaan van der Donck and Johannes Visscher. Bent wood frames were covered in slabs of bark, often with fur hangings as the doorways. Central fires ensured the homes were warm in the winter.

A 1682 deed for land (for free and forever) in Queens County includes marks written by two native brothers named Munguab and Panum. The native tribes in the area did not conceive of land as something that could be owned, at least not in any absolute or permanent sense. A Booke of Enterys in Queens County on Long Island [Deeds and Wills], 1683-1713. Old Town Records. Courtesy of the Municipal Archives, City of New York.

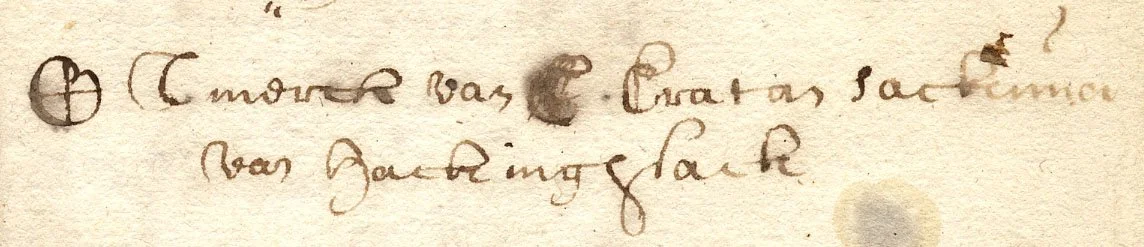

Chief Oratam of the Hackingsack Indians was named in the Indian Deed for Staten Island in 1657 as one of the hereditary owners of Staten Island. His mark and the Dutch scribe’s notation from this document is included above.

Oratam or “Oratamy/Oritani/Oratamin’’ appears to have been a person much respected by both the Native American and Dutch Colonial people, as he was involved in negotiating peace treaties, deeds, etc. for many years, and lived to be approximately 90 years old. His friendship with Sara Kierstede evolved from their mutual work in translations and negotiations.

Indian deed to Lubbertus van Dincklage, attorney of Henrick van der Capelle tho Ryssel, for the whole of Staten Island, called by the Indians Eghquaons, July 10, 1657. New York State Archives. New York (Colony). Council. Dutch colonial administrative correspondence, 1646-1664. Series A1810-78. Volume 12, document 61, side 1. Translated in: Correspondence, 1647-1653, trans. and ed. Charles T. Gehring.

“We, the undersigned natives of North America, hereditary owners of Staten Island, Sackis of Tappaan, Taghkoppeauw of Tappaan, Temeren of Gweghkongh, Mattenou of Hespatingh, Waerhinnis Couwee of Hespatingh, Weertsjan of Hackingsack, Kekinghamme of Hackinchsack, Wewetackenne of Hackinghsack, Neckthaa of Hackinghsack, Minquasackyn of Hweghkongh, Terincks of Hweghkongh, Mikanis of Gweghkongh, Mintames Seevio of Gweghkongh, Acchipior of Hweghkongh, certify and declare for ourselves and our descendants in presence and with the knowledge of the underwritten witnesses, to have sold and conveyed as a free hereditable property now and forever without any further claims to be made by us or our descendants to Lubbertus van Dincklaecken, attorney for his right honorable Henrick van der Capellen tho Rijssel, the whole of Staten Island, by us called Eghquaons, for the goods hereafter specified, to be brought from Holland and delivered to us, the owners.

10 boxes of shirts; 10 ells of red checked cloth; 30 pounds of powder; 30 pairs of Faroese stockings; 2 pieces of duffel; some awls; 10 muskets; 30 kettles, large and small; 25 adzes; 10 bars of lead; 50 axes, large and small; some knives.”

—July 10, 1657

Indian deed to Lubbertus van Dincklage, attorney of Henrick van der Capelle tho Ryssel, for the whole of Staten Island, called by the Indians Eghquaons, July 10, 1657. New York State Archives. New York (Colony). Council. Dutch colonial administrative correspondence, 1646-1664. Series A1810-78. Volume 12, document 61, side 1. Translated in: Correspondence, 1647-1653, trans. and ed. Charles T. Gehring.

“In witness whereof we the owners have signed this with the witnesses in due form of law on the land of Waerhinnis Couwee at the Hespatingh near Hachinghsack in New Netherland the 10th of July 1657.

Waerhinnis Couwe, Nechtan, Saccis, Mattenouw,Taghkoppeeuw, Temeren, Weertsjan, Kekinghame, Wewetachamen, Minqua Sackingh, Nuntuaseeuw,Teringh, Achspoor, Oratam, Pennikeck, Keghtackaan, Keghtakaan, Teringh, Waerhinnus, Couwe, Mattenouw