The Attica State Prison uprising in September, 1971 that resulted in 43 deaths had a profound effect on the Prisoner’s Rights movement. Some prisoner’s rights activists argue that Attica resulted from prison conditions and abuses routine in American prisons. On the other hand, administrators blamed the incident on a lack of oversight and security measures. Another important factor was the rural location of a prison housing predominantly black and brown prisoners, guarded by white officers. Regardless of the contrary views, the loss of lives at Attica and destruction of property had a profound effect on the nation, and on New York City, the home of 20 deceased inmates.

About a year before the uprising in Attica, New York City experienced a series of incidents in its detention centers. On August 10, 1970, inmates at the Manhattan Detention Center Complex, known most commonly as The Tombs, held five correctional officers hostage for eight hours on the ninth floor of the facility. Mayor John V. Lindsay successfully negotiated the release of the hostages, promising to fulfill prisoner’s demands including speedy trial deliberations, better food, and less overcrowding. Unfortunately, the city fell short in fulfilling the promise.

On October 2, 1970, riots broke out at a Queens detention center in Long Island City, spreading to The Tombs. Over the next two days another riot was reported at a detention center in Kew Gardens. The ordeal resulted in 23 officers held hostage and the takeover of various cell blocks, which prompted Mayor Lindsay to halt the intake of new prisoners temporarily.

In addition to riots, the detention centers experienced a number of prisoner suicides. The poor conditions in The Tombs continued to decline, and Mayor Lindsay pleaded with New York State Governor Nelson Rockefeller to transfer state prisoners to state custody. The governor agreed to take approximately 500 prisoners some of whom ended in Attica State Prison. One of those prisoners, Samuel Joseph Melville, was a leader of the Attica uprising and perished there. Melville had been charged with plotting and planting bombs in eight of the prison's administrative buildings.

On September 9, 1971, inmates at Attica State Prison who were locked in a tunnel battered down the gate and began an insurrection in which theyeventually occupied the central control room and the D Prison yard. The prisoners held over 50 hostages (later releasing 12 for medical reasons) and communicated a list of 32 demands (subsequently reduced to 28) which included access to medical care, fresh fruit, fair visitation rights and amnesty for the uprising. Attempts to negotiate failed. Four days later, on the morning of September 13th, the NY State Police and prison guards stormed the prison and indiscriminately opened fire. After retaking the prison, correction officers took revenge on the perceived leaders. By the end, 30 inmates and 8 hostages perished with many others wounded. Additional victims included three inmates and one correctional officer who perished before the state police entered the prison and a tenth hostage who died from complications a year later.

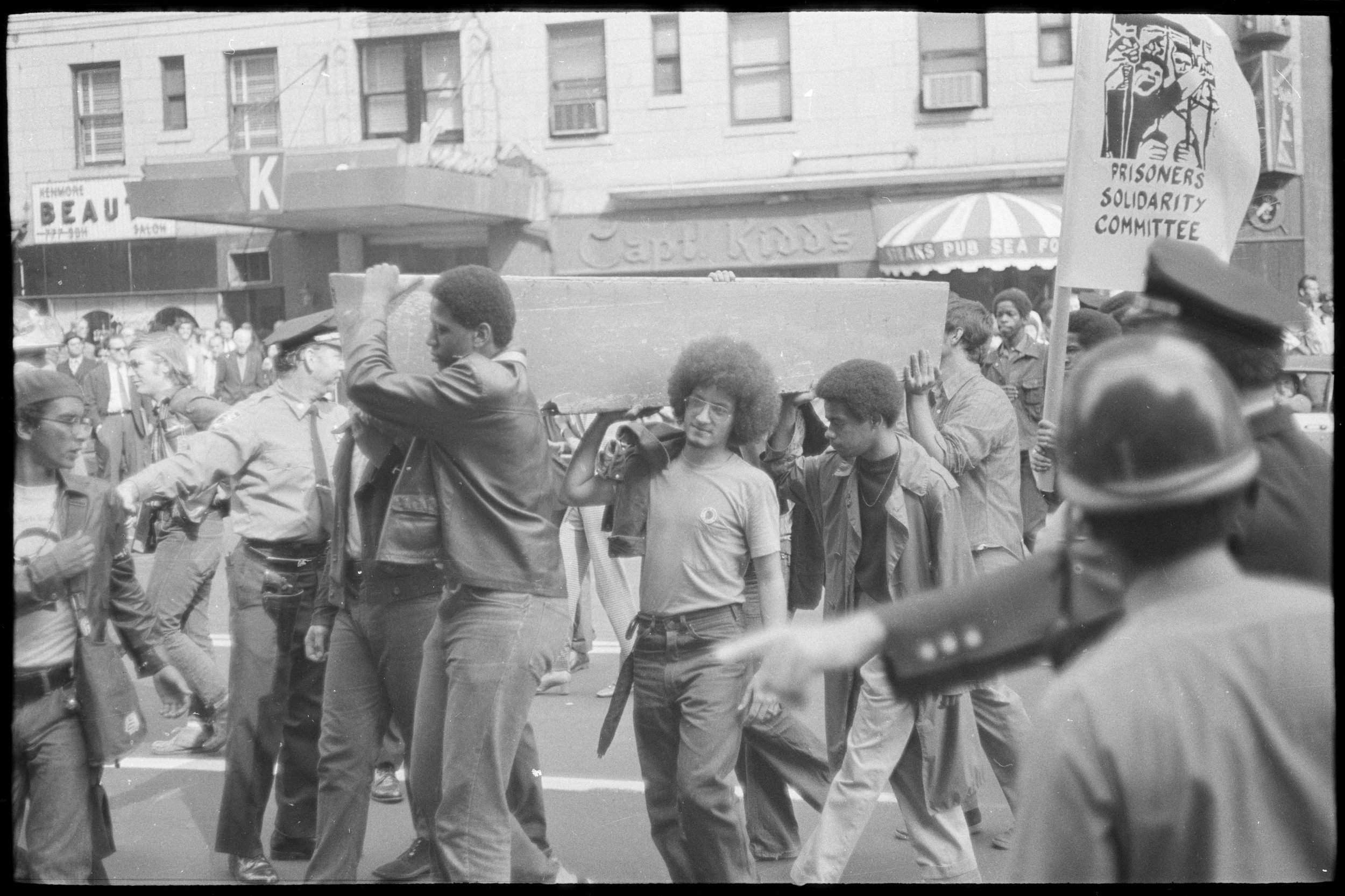

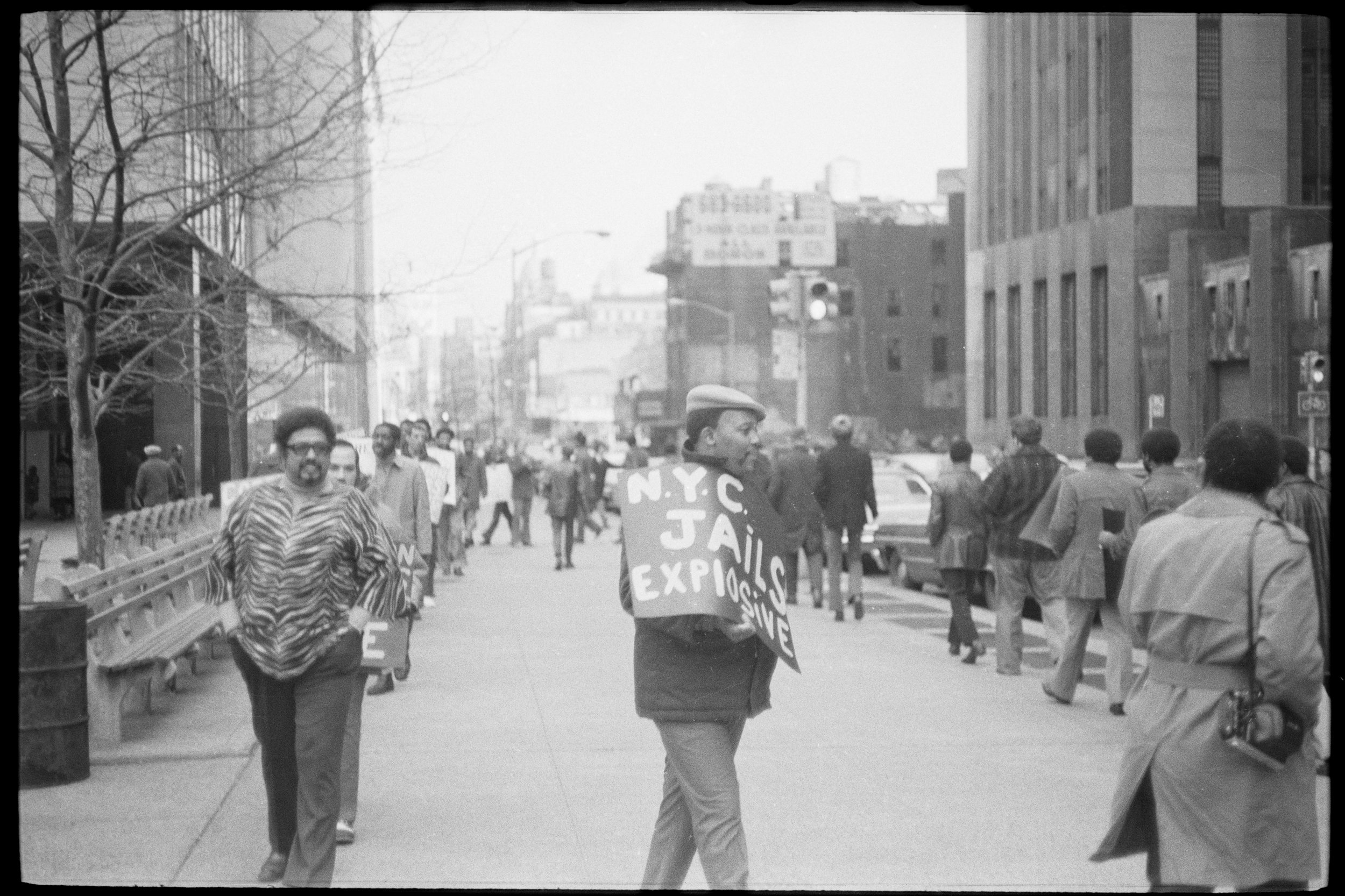

Because of New York City's struggles with inmates and its connection to a number of the victims, the city erupted in protest. Adding to the tension was Governor Rockefeller's refusal to accept responsibility and the conflicting reports about the events that led to the loss of life in Attica. Immediately following news of the tragedy, The Prisoners Solidarity Committee and Youth Against War and Fascism gathered outside of Rockefeller’s office on West 55th Ave to protest the actions of Governor Nelson Rockefeller and the New York State Police. Around 500 people attended the rally including members of The Young Lords, the Black Panther Party and the Gay Activists Alliance. For several days, demonstrators stood outside Rockefeller’s office and his residence to protest what they viewed as an unjust use of force.

On September 18, 1971 over 1500 people gathered for a rally hosted by Youth Against War and Fascism and other groups in Union Square, followed by a march to Rockefeller Center where demonstrators burned Nelson Rockefeller in effigy. Speakers at the rally included William King from the Black Panther Party 21 and Julian Beck from Living Theatre.

Demonstrators gathered at 125th St. for another rally and one contingent marched from Willis Ave in the Bronx to join the march in Harlem. The event feature Charles Kenyatta as the MC, William Kunstler, a lawyer present at the Attica uprising, and Juan Ortiz, a member of The Young Lords. Over 500 people attended the event including U.S Representatives Herman Badillo and Charles Rangel.

On October 31st, 1971 a People’s Tribunal was held by the New York Chapter of the Black Panther Party which found President Richard Nixon, Governor Nelson Rockefeller, and other individuals guilty of atrocities at Attica. Demonstrations against the actions of Rockefeller were not limited to New York City; New York state correctional facilities in Clinton and Elmira also experienced protest by inmates. Additional large scale demonstrations took place in Boston and Washington, D.C.

The funeral services for inmates were well attended. On September 24, 1971, after being denied permission to hold a viewing at the Bedford Stuyvesant Armory, six males, accompanied by nearly 200 others, broke into the armory, carrying the caskets of Thomas Hicks, Rafael Vasquez, Harold Thomas, John Barnes, Emmanuel Johnson and Frank Williams. A day later the bodies were taken to Cornerstone Baptist Church for a memorial service with 700 people in attendance. The Congress of African People paid for the burial expenses. Other well attended funerals included that of Samuel Melville at Washington Square United Methodist Church and that of Ramon Rivera, a Young Lords member.

The fervor of the post-Attica demonstrations and the national outrage over the incident led to some prison reforms in New York City and State. In the following year, the state implemented many of the prisoner demands including increasing medical staff and clergy, relaxing visitation regulations and increasing the number of African American and Latino officers. In 1970, New York City Mayor John Lindsay appointed the first African American Corrections Commissioner, Benjamin Malcolm, and reduced delays between conviction and sentencing. But, the violence at Attica also reduced public support for long-term, meaningful reform.

Today, the Attica uprising continues to evoke powerful emotions. Thirty years after the event, in January, 2000, the State of New York paid a settlement to the families of those who were killed at Attica, and in 2015, after much demand, the State released the Meyer Report which addressed Attica riot.