New York City is a seaport. Always has been. Even before Giovanni da Verrazzano sailed into the harbor in 1524 and declared it “a very agreeable place [where] a very wide river, deep at its mouth, flowed out into the sea,”(1) the Lenape had established trading centers along the shore. The City’s shoreline has played a vital role in the regional, national, and global economy. With more miles of shoreline (520!) than the harbors of Boston, Miami, Los Angeles and San Francisco combined,(2) New York’s waterfront has been the site where goods got loaded and unloaded, where a slave market existed, where immigrants arrived by the millions, and where ships got built, fish were landed, people swam, and water to make beer was piped in while sewage was piped out—sometimes in appalling proximity. Our shoreline has been used for many things over the centuries and has expanded significantly through the use of fill.

Documentation of the precise shape and myriad uses of New York City’s waterfront is of interest to scholars, to developers, and to engineers and scientists planning for a resilient city facing the challenges of climate change. Given that our land-water interface has been in constant flux, where can accurate data about it be found? One rich repository of shoreline data is a set of more than 2,000 hand-drawn maps of the waterfronts of all five boroughs, many dating back to surveys conducted in the 1890s. The maps bear annotations indicating that they were updated and actively used well into the 1960s. They were prepared by surveyors and cartographers working for the city’s Department of Docks and its successor agencies,(3) and make up collection REC0133, entitled Waterfront Survey Maps.

Figure 1. Top: the corner of a Waterfront Survey Map showing the extent of damage from age and heavy use. Bottom: close-up of a waterfront map showing the careful reference to surveyor’s books that provided the data for map preparation.

The collection includes a diverse set of drawings and related materials, but the core materials are hand-inked maps measuring approximately 27” x 40”, drawn to a scale of 1”:50’, with annotations linking them to a collection of surveyor’s notebooks. Many of the maps (which have all been physically conserved) show evidence of heavy use. The maps’ margins have in some cases literally crumbled away—alarming to the archivist, but evidence of the heavy use to which they were put.

The collection has not been analyzed to determine exactly how much of New York’s 500 miles of waterfront is represented. Some of the most heavily industrialized neighborhoods, such as Newtown Creek on the Queens/Brooklyn border, appear in numerous maps. An interactive map that locates each map in the collection on a contemporary digital map, as has been done(4) for the Municipal Archives’ collection of 1940s tax photos,(5) would be very helpful (interns, take note!)

To illustrate the extraordinary detail in these maps and their potential value, let’s look at a stretch of waterfront that is perhaps not the first that comes to mind as one of the city’s most active or interesting shorelines: the Hudson River shore on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, starting around 59th Street and extending eight miles uptown to the northern tip of the island.

Ever since this stretch was reconfigured by Parks Commissioner Robert Moses in the late 1930s as part of his West Side Improvement Project using 25 million Depression-Era dollars secured from the Roosevelt Administration, as vividly recounted by Robert Caro in The Power Broker, the Upper West Side has worked to regain access to its waterfront. Moses doesn’t deserve all the blame—the Hudson River Railroad built tracks that hugged the river in 1849,(6) removing access to the water except for a handful of pedestrian bridges and dangerous grade-level crossings. The result was a mashup of industrial and recreational establishments that waxed and waned until Moses imperiously put an end to them all in 1934, reconfiguring Riverside Park, burying the railroad tracks under the park, and constructing the West Side Highway to facilitate access by car and truck to midtown and downtown Manhattan from the outer boroughs and suburbs. The Waterfront Survey Maps collection includes an overlapping series of drawings that span this stretch of Manhattan and reveal a fascinating set of long-forgotten features.

For example, the Hudson River Park and Greenway that now grace the shoreline starting at West 60th Street lie on top of an extraordinary feat of engineering: at least half a dozen piers and dozens of train tracks fanning out from an enormous railroad roundhouse near 72nd Street that distributed train cars arriving from upstate as well as those that were floated across the river from New Jersey and pulled off their barges at the Transfer Bridges whose ruined remains can still be seen in the water off 69th Street. Only vestiges of this industrial complex have been preserved, but the Survey Maps shows it in exquisite detail.

Figure 2. Top left: Waterfront Survey Map wsm_s-255 showing Hudson River from 59th to 74th Streets. Top right: close-up with detail of NY Central Railroad roundhouse. Center: undated photo of 60th Street freight yard showing roundhouse for turning engines, numerous tracks, and the float or transfer bridges bringing freight cars from New Jersey on barges. Lower left: close up of map with transfer bridge detail. Lower right: remnants of transfer bridges in the Hudson today.

Immediately upriver from the roundhouse was a vast timber basin—a protected stretch of shore with booms that enclosed a kind of harbor where large quantities of wood used in construction were offloaded from ships and kept afloat until needed. Timber basins were familiar sights near shipyards, but Manhattan’s vast consumption of wood for railroad and subway ties as well as in building construction justified a timber basin on the Hudson; the basin at West 75th Street lasted from the mid-1890s until the mid-1920s. The few existing photographs of the timber basin hint at its size and nature; the Waterfront Survey Map for this stretch add details such as the dimensions of its opening to the river, and the advancing shoreline that eventually filled in the basin.

Figure 3. Top: detail from Figure 2 showing timber basin boom and (inset) close-up with dimensions of basin’s opening to the Hudson River. Note penciled annotations for the location of the riverbank at different times. Bottom: rare photo of 75th Street timber basin from Department of Ports and Trade photographs collection, New York City Municipal Archives.

Starting with the Columbia Yacht Club at 86th Street, the survey map collection documents an astonishing number of boat, canoe, and yacht clubs as well as several swimming clubs—enclosed areas where swimmers could change, lounge, and take dips in the Hudson River while remaining protected from the vagaries of the open river. In the early 20th century, these clubs stretched all the way to Spuyten Duyvil at the northern tip of the island and were particularly dense in Inwood.

Figure 4. Top left: waterfront survey map showing cluster of boat clubs in Fort Washington. Top right: fire insurance map showing much less detail. Lower left: 1924 aerial photo. Lower right: modern satellite photo showing empty shoreline.

At 97th Street, the US Navy maintained a surprisingly robust presence. The survey maps show the outline of the USS Granite State, a remnant of the War of 1812 (!) that served as a training vessel for sailors while docked here from 1910 until she caught fire and burned in 1922. The maps also show onshore Navy facilities that aren’t documented on other contemporary maps.

Figure 5. Top: Waterfront Survey Map showing extensive US Navy structures at West 97th Street with numerous updates in black, red, gold, blue, and green ink. The massive docked ship is the USS Granite State, whose hull outline is marked with a series of red x’s because the ship burned in 1921 (lower photo).

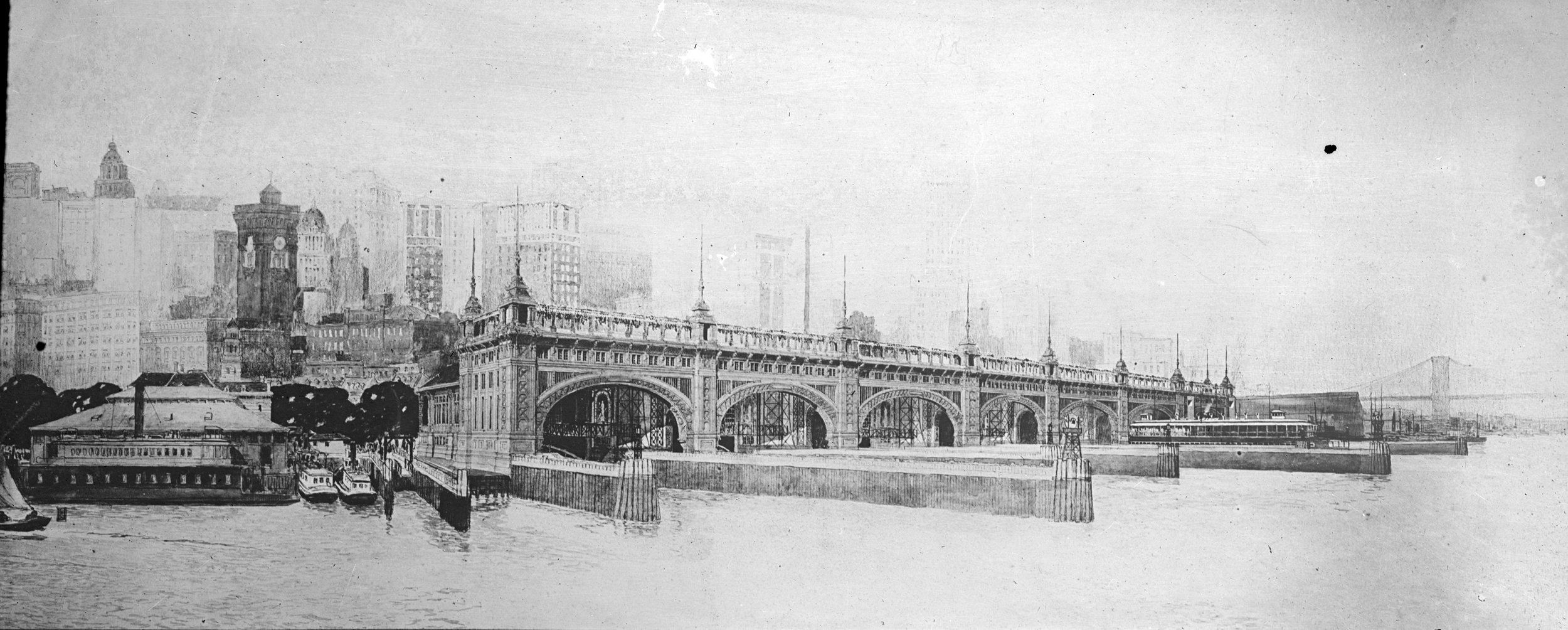

New York City’s biggest celebration ever may have been the Hudson-Fulton Centennial in 1909. A highlight among the many festivities was a naval parade in the Hudson River. The city built an elaborate “watergate” at 110th Street to welcome global dignitaries from the ships anchored in the Hudson. The survey maps document not only the precise location and dimensions of the water gate but also the date of its removal—information that is difficult to locate elsewhere.

Figure 6. The impressive faux-marble water gate built to welcome dignitaries to the Hudson-Fulton Centennial Celebration in September 1909. Top: waterfront survey map detail showing the floating wooden platforms and the footbridge over the NY Central train tracks, all rich with dimensions. The tiny but careful red x’s indicate that the entire structure was removed, as the annotation indicates, on 7 June 1911. Bottom: Municipal Archives photo of the water gate, with a reproduction of Robert Fulton’s Clermont at dock and the newly completed Hendrik Hudson apartment building at West 110th Street in the background.

The detail recorded in the Archives’ waterfront maps is quite extraordinary, as was the careful noting of changes over time, achieved by drawing updates in different color inks. These maps compare favorably to another important historic resource for Manhattan—fire insurance maps. Prepared by private engineers and cartographers rather than a city agency, fire insurance maps are popular with historians for their frequent updates and their building-by-building detail. However, most either stopped their coverage at the closest marginal road to the waterfront or included far less information than the waterfront survey maps do, where their coverage overlapped. The industrialized waterfront in Manhattanville, where West 125th Street extended all the way to the Hudson, provides a final example. This was the location of the Fort Lee Ferry docks. The extensive system of pilings, piers and a ferry terminal are long gone (the terminal building was removed in 1959, for example. How do we know? —map wsm_s-264 tells us so!), but the maps reconstruct this busy strip of waterfront in exquisite detail. Compare the state-of-the-art Bromley fire insurance map of 1934 to the Municipal Archives’ Waterfront Survey Map of the same area. The Archives’ map is incomparably more detailed, right down to the humble lunch stand that can also be seen in a superb photo taken in 1915 by Eugene de Salignac, legendary photographer of the Department of Plant and Structures. (7)

Figure 7. Manhattanville ferry docks. Top: head-to-head comparison of Waterfront Survey Map and fire insurance map of the same area. Game over. Middleleft: closeup of waterfront map showing palimpsest of numerous superimposed updates. Middleright: Municipal Archives photograph of the Riverside Drive viaduct. Bottom: closeup from photo confirming “Lunch Stand” notation on Waterfront Survey Map.

Nearly all the materials in the Waterfront Survey Map collection have been digitized, and with the completion of a finding aid it is more accessible than ever, to scholars and to anyone with an interest in a detailed understanding of the evolution of New York City’s shoreline.

[1]https://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/amerbegin/contact/text4/verrazzano.pdf

[3] According to notes made by archivists Amy Stecher and Ian Kern in 2018, the agencies that succeeded the Department of Docks as functions and responsibilities evolved were: Department of Docks and Ferries, 1898-1919; Department of Docks, 1919-1942; Department of Marine and Aviation, 1942-1969; Department of Ports and Terminals, 1968-1985; Department of Ports, International Trade and Commerce, 1985-1986; and Department of Ports and Trade, 1986-1991. Following the revision of New York City’s charter in 1990, the responsibilities of the Department of Ports and Trade were incorporated into those of the Economic Development Corporation (EDC), which exists today. Collection REC0133 was accessioned by the New York City Municipal Archives in 1992-1993 from the EDC, which had maintained these records in the Battery Maritime Building.

[4] 1940s.nyc

[5] https://a860-collectionguides.nyc.gov/repositories/2/resources/64

[6] Anonymous. 1851. Hudson River and the Hudson River Railroad, 10-12.