There is, in the Municipal Library, a charming tome titled The Eastern District of Brooklyn with Illustrations and Maps. Published on May 7, 1912, its author, Eugene L. Armbruster, was a preservationist long before that was a recognized field. An immigrant from Germany to the United States, he devoted years to documenting Long Island (which included Brooklyn and Queens) with photographs, pamphlets and other publications. Thousands of his photos are in collections at the New York Historical Society, the Brooklyn Public Library and the Queens Public Library.

Ferry Landing, Grand Street, Williamsburgh, 1835. Illustration from The Eastern District of Brooklyn with Illustrations and Maps, 1912. NYC Municipal Library.

Armbruster frequently answered questions posed by readers of The Brooklyn Eagle in a section of the paper titled “Questions Answered by the Eagle.” This idiosyncratic feature contained a hodge-podge of information in response to inquiries such as, “Is there a Shenandoah in New York?” submitted by BLANK…. Yes, in Dutchess County. “What is meant by the seven ages of man and who was the author?” posed by Mrs. D.H. … It’s from As You Like It by William Shakespeare spoken by the Duke in Act 2 (although the better-known portion of that speech is “all the world’s a stage and all the men and women merely players”). Labeled “the local expert on Brooklyn history,” Armbruster fielded questions related to events and places in Brooklyn, such as the original location of Litchfield Mansion. Right where it remains at 5th and 9th Ave., also known as Prospect Park West.

The book itself is tiny, about the size of a box of notecards but it contains a host of information in its series of brief sketches, appendices and hand-drawn illustrations and maps. The titles themselves are beguiling: a settlement named Cripplebush, one appendix titled, “The Solid Men of Williamsburg, 1847,” and the illustration listed as Literary Emporium. Is there such flora as a cripplebush and if so, what does it look like? Were the Williamsburg men particularly chunky? Was the emporium a bookstore or early library? The answers lie ahead.

Junction of Broadway, Flushing and Graham Avenues. Illustration from The Eastern District of Brooklyn with Illustrations and Maps, 1912. NYC Municipal Library.

Written shortly after the consolidation of the Greater City in 1898, the author intended to provide an overview of the Eastern District of Brooklyn to assist future historians. “If a history of the City of New York will ever be written, its compiler will look around for historical matter relating to the old towns, now forming parts of the metropolis, and this book was written that the Eastern District of Brooklyn may be represented then. But, what exactly is this Eastern District? Armbruster explained that during an earlier Kings County consolidation, the towns of Williamsburg, Bushwick and North Brooklyn were combined into the Eastern District. There also was a Western District that “included the remainder of the enlarged city” which was the portion of Kings County that comprised the City of Brooklyn. But that’s not all. There was a “sparsely settled” 9th ward between the two districts and a 26th ward that “was never a part of the Western District, but a town by itself until annexed in 1886 by the late City of Brooklyn.” Clear as mud!

Suffice it to say that the book is about a series of settlements that became villages, towns and cities between 1638 and 1910. These include what are now Ridgewood and Long Island City (now in Queens), Bushwick, Greenpoint, Williamsburg and East New York. The boundaries of the settlements shifted based on grants issued by the West India Company, colonial governments and eventually through Acts of the State Legislature.

Armbruster appears not to have accessed primary source documents and instead relied on several historical analyses. Mostly but not entirely written in the mid-to late 19th century, the authors include Henry R. Stiles, a physician and historian who penned the multi-volumed The Civil, political, professional and ecclesiastical history, and commercial and industrial record of the County of Kings and the City of Brooklyn, N.Y. from 1683 to 1884, and E.B. O’Callaghan who is best known for his (flawed) translation of original Dutch government and West India Company records.

Burr & Waterman’s Block Factory, Kent Avenue and South 8th Streets, 1852. This factory made “patent blocks” bricks of patented designs that were stamped with a company logo. Illustration from The Eastern District of Brooklyn with Illustrations and Maps, 1912. NYC Municipal Library.

One issue with the writing is the description of Native Americans in derogatory terms that are based on a versioning of history in which the European settlers were beneficent and the original residents of the land somehow miscreants. For example: “Over the morass led narrow trails, known to the redskins and the wild beasts, but treacherous to strangers.” Even when reporting on the murder of Native American families ordered by the Director General Willem Kieft, Armbruster maintains this form.

“In an evil hour Kieft ordered some of his men to the tobacco-pipe-land and another band to the Indian village, Rechtauk, situated two miles north of the fort on the East River (the present Corlear’s Hook), while both places were occupied by some fugitive Wesquaesgeek Indians, and had them cruelly slaughtered, men women and children, under cover of night. When the savages found out that the white men had committed the outrage, which they had first believed to be the work of an hostile Indian tribe about a dozen of the neighboring tribes of River Indians rose up against them and attacked the several plantations.” Who, one asks, should be more appropriately termed savage?

He devotes a brief chapter to the town records of Bushwick (Boswijck from “bos,” meaning a collection of small things packed close together, and from “wijk”—retreat, refuge, guard, defend from danger). This topic interests researchers and staff at the Municipal Archives. “When Bushwick became part of the City of Brooklyn the records were, in accordance with an article of the charter of the enlarged city, deposited in the City Hall. They were sent there in a movable bookcase, which was coveted by some municipal officer, who turned its contents upon the floor, whence the janitor transferred them to the papermill.”

Not all went to the papermill. The Municipal Archives collections includes the Old Town records which includes 60 volumes from the towns and villages in Kings County during the Dutch and English colonial periods.

In one beautifully written paragraph, Armbruster describes the rise and fall of the four mile stretch of Nassau River, known at the time of publication and today as Newtown Creek. “In the background were the hills covered with trees… At that time the creek, with the several gristmills, and the farms bordering thereon, differed in no way from the rural scenes, which are often seen as typical of Holland, except for the hills in the background. But since then the mills have vanished and factories and coal yards have taken their places and commercialism in general, with no eye for landscape beauty has taken hold of the territory. The water of the creek has been polluted to such a degree that the name of Newtown Creek has come into ill-repute, and it is well that the waterway, when cleansed and improved, will be known by the euphonious name of Nassau River.

Williamsburgh Gas Works Office, 93 South 7th Street, 1852. Illustration from The Eastern District of Brooklyn with Illustrations and Maps, 1912. NYC Municipal Library.

Phoenix Iron Works, 230 Grand Street, 1852. Illustration from The Eastern District of Brooklyn with Illustrations and Maps, 1912. NYC Municipal Library.

On the list of federal Superfund sites for the past decade, perhaps when the Environmental Protection Agency does undertake cleaning up the toxic waste, Newtown Creek will be again named Nassau River.

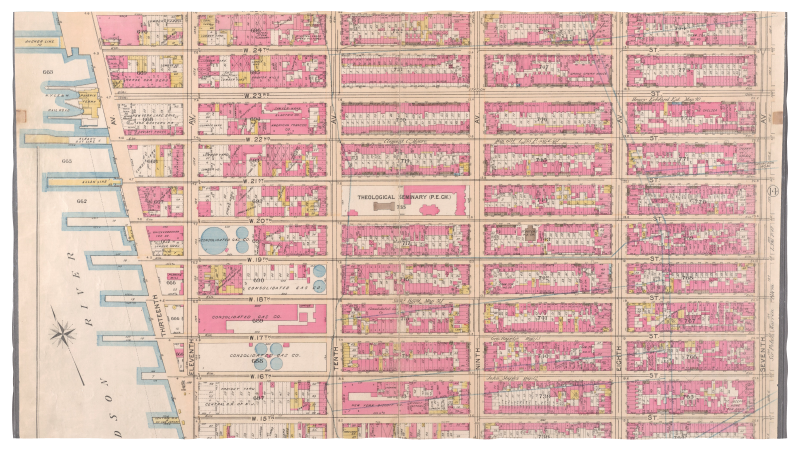

Map of the area north of Newtown Creek. Illustration from The Eastern District of Brooklyn with Illustrations and Maps, 1912. NYC Municipal Library.

The appendices include three sections providing census information. Number 9 from the Census of Kings County circa 1698, lists the names of freeholders, and enumerates their family members, apprentices and enslaved people within Kings County “on Nassauw Island.” There were 51 freeholders, including four women. Eleven were of French ancestry; one was English and the remaining 39 were Dutch. In addition to the freeholders there were 49 women (presumed wives) 141 children, 8 apprentices and 52 enslaved people.

Appendix Number 12 provides the number of all inhabitants in the Township of Bushwyck, male and female; black and white, in 1738. The total of 325 “Ziele” (souls) listed 41 freeholders, including six women. There were 119 white males; 130 white females, 42 black males and 36 black females.

Appendix 13 offers a list of householders in one district of Bushwick. The 22 householders enslaved 20 men and 21 women.

A list of all the Inhabitants of the Township of Bushwick-Both White and Black-Males and Females, in 1738. An illustration from The Eastern District of Brooklyn with Illustrations and Maps, 1912. Appendix XII. NYC Municipal Library.

This data shows that the colonial households and economy of Bushwick grew increasingly reliant on slave labor. The 1698 census shows that 21 households included enslaved people and five of the 30 remaining households listed apprentices. By 1738, 25 of the 41 households in the census listed black residents, who we presume were enslaved.

And now, to our initial questions.

Cripplebush was an area of land that stretched from Wallabout Bay to Newtown Creek and so named because of the thick scrub oak that flourished there, which the Dutch called kreupelbosch meaning thicket. The actual hamlet, which received a patent in 1654 was located around what today is South Williamsburg, just north of the Marcy Houses operated by NYCHA.

In 1847, a publication was issued listing the men of Williamsburgh and City of Brooklyn who owned $10,000 or more in personal property or real estate. The Solid Men of Williamsburgh refers to the 44 men living in that town who met this economic threshold.

As for the Literary Emporium—who knows. The illustration does not offer a clue as to its purpose.

Literary Emporium, corner of 5th and Grand Streets, 1852. Illustration from The Eastern District of Brooklyn with Illustrations and Maps, 1912. NYC Municipal Library.