“The rhythms protected us...”

“The rhythms gave us... faces”

—Willie Colón in Low Rent: A Decade of Prose and Photographs From the Portable Lower East Side, Kurt Hollander, 1994, p. 90.

Willie Colón and Héctor Lavoe (1969 Fania Records publicity photo), Public Domain.

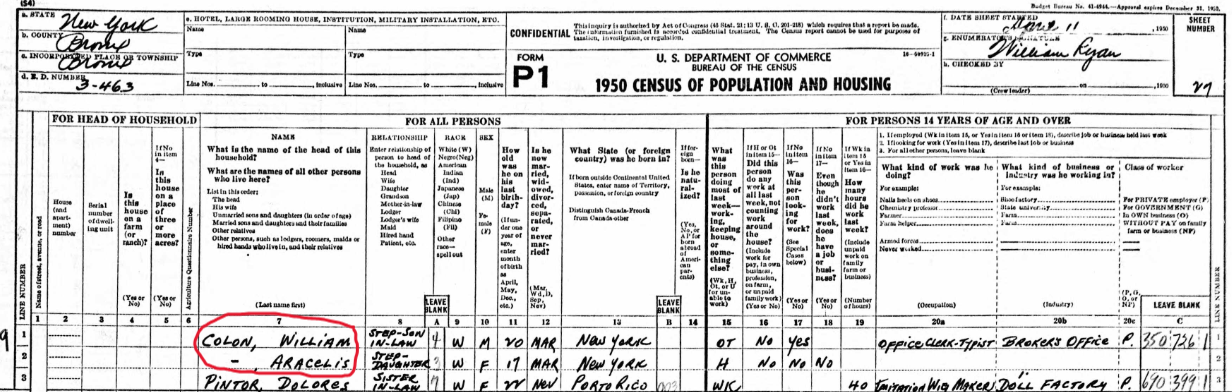

1950 Census Record showing Willie’s parents, William and Aracelis Colón.

695 East 139th Street, where Colón grew up, 1940s Tax Photos. NYC Municipal Archives.

Willie Colón, the King of Salsa, was born on 139th Street in the South Bronx on April 28th, 1950. Born William Anthony Colón Román, he was later known as El Malo Del Bronx (based on his debut album title) and referred to as El Maestro. Colón always recalled his Abuela (Grandmother), Antonia Pintorette, originally from Manatí, Puerto Rico, as being his primary caregiver.

Inspired by the street rhythms emanating from congas, bottles, and tin cans that he described as lullabies, Colón picked up the trumpet at age twelve. Two years later, he switched to trombone, which became his instrument of choice. Colón released his first album, El Malo, at age 17 in 1967 on Fania Records newly formed by Johnny Pacheco and Jerry Masucci. From there, he went on to help define the genre of salsa that took New York City and the world by storm. He collaborated with icons like Celia Cruz, Rubén Blades, Héctor Lavoe, and many others. He played in the Fania All Stars Band, became director of the Latin Jazz All Stars, and won multiple awards and accolades for his music.

The 1973 Fania All Stars concert at Yankee Stadium, recorded August 23rd, brought 40,000 salsa fans to see Celia Cruz, Héctor Lavoe, and Willie Colón.

Along with an abundance of Latin American artistic talent arising from the South Bronx, Colón helped compose the soundtrack of the area in the late 20th century—decades that saw political, economic, and social turmoil and change. Confronted with a “burning Bronx,” massive recession, redlining policies and diversifying neighborhoods, Latin American musicians from Puerto Rico, Colombia, Cuba, Panama, and more expressed stories, experiences, joy, and struggles through music, like salsa. Later, Colón wrote,

“We easily turned 139th Street into a tropical barriada. All the stores in the area had Spanish signs in front. In the mornings you could hear the radios blaring those Latin rhythms in an eerie but reassuring echoey unison—and the smell of hundreds of pots of Cafe Bustelo filling the air.”

Aerial photo of South Bronx showing Yankee Stadium, from New York (N.Y.). Police Department. Aviation Unit. NYC Municipal Archives.

Salsa music and the South Bronx go hand in hand. With an influx of migrants from Latin America and Puerto Rico to New York City in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, many neighborhoods turned into hubs for Latin and Nuyorican culture. The sounds of the islands, mixtures of Afro-Caribbean, Taíno Indigenous, Latin Jazz, merged with cutting edge beats and vocals of R&B and Hip-Hop. Bronx legends like Tito Puente, Ray Barretto, Rubén Blades, Joe Bataan, and La India took the area by storm. One could not travel far down The Hub or Southern Boulevard without hearing congas, claves, and chants thundering from cars, windows, and boomboxes.

Tito Puente, contemporary of Colón, performing at City Hall, from WNYC, New York Hotline: Episode 401 - El Fieston de Nueva York, a Latin cultural festival, May 13, 1992.

Willie Colón distinguished his music from other salsa at the time with songs that brought to the forefront issues around identity, discrimination, and Colonization particular to Latin American experiences. Songs like Todo Tiene Su Finale (written by Héctor Lavoe in 1973), Pedro Navaja (written by Rubén Blades in 1978), and El Gran Varón (written by Omar Alfanno in 1986), told complex stories of love, life, and death.

Willie Colón featuring Héctor Lavoe & Yomo Toro - Aires de Navidad - Live/En Vivo, Fania Records, circa 1971.

Throughout his career, Colón studied composition, orchestration, and arrangement, constantly revising his writing and performance practices. Many describe his songs as helping to connect Nuyoricans back to the island, as they inspired affection, celebration, and pride in Puerto Rican identity. Following news of Colón’s passing, his manager Pietro Carlos wrote:

“Willie didn’t just change salsa; he expanded it, politicized it, clothed it in urban chronicles, and took it to stages where it hadn’t been heard before. His trombone was the voice of the people, an echo of the Caribbean in New York, a bridge between cultures.” (FB)

Héctor Lavoe y Willie Colón - Presentación en los PBS Studios, NYC (1972).

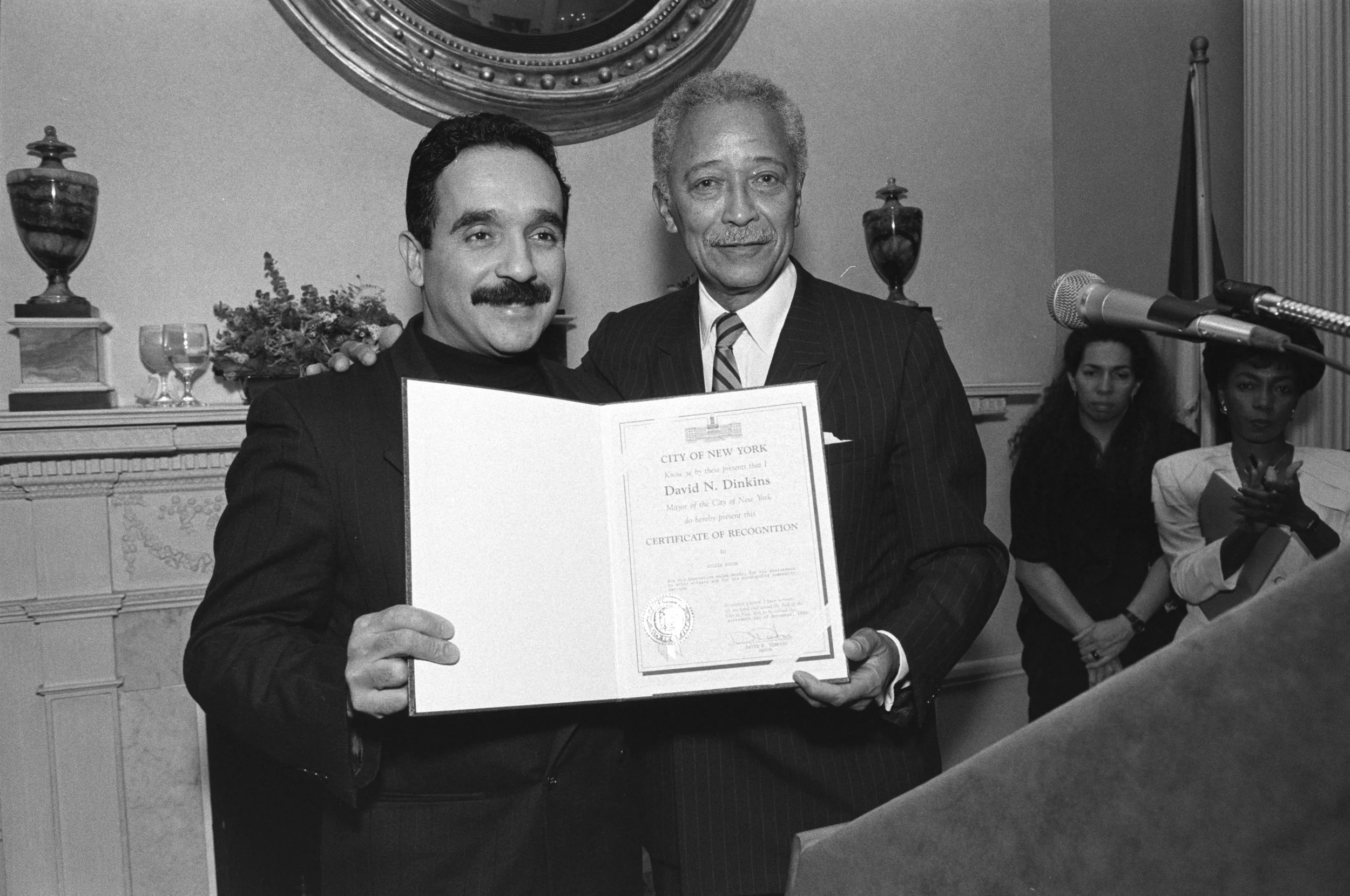

Eventually, Willie Colón’s political interests influenced other aspects of his life. He advocated for social justice, most notably HIV/AIDS, Hispanic and Latin American representation in the U.S., and local political institutions. He was part of the Hispanic Arts Association, the Latino Commission on AIDS, the Arturo Schomburg Coalition for a Better New York, and the Congressional Hispanic Caucus Institute. In 1995, Colón became the first person of color to serve on the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers’ (ASCAP) national board.

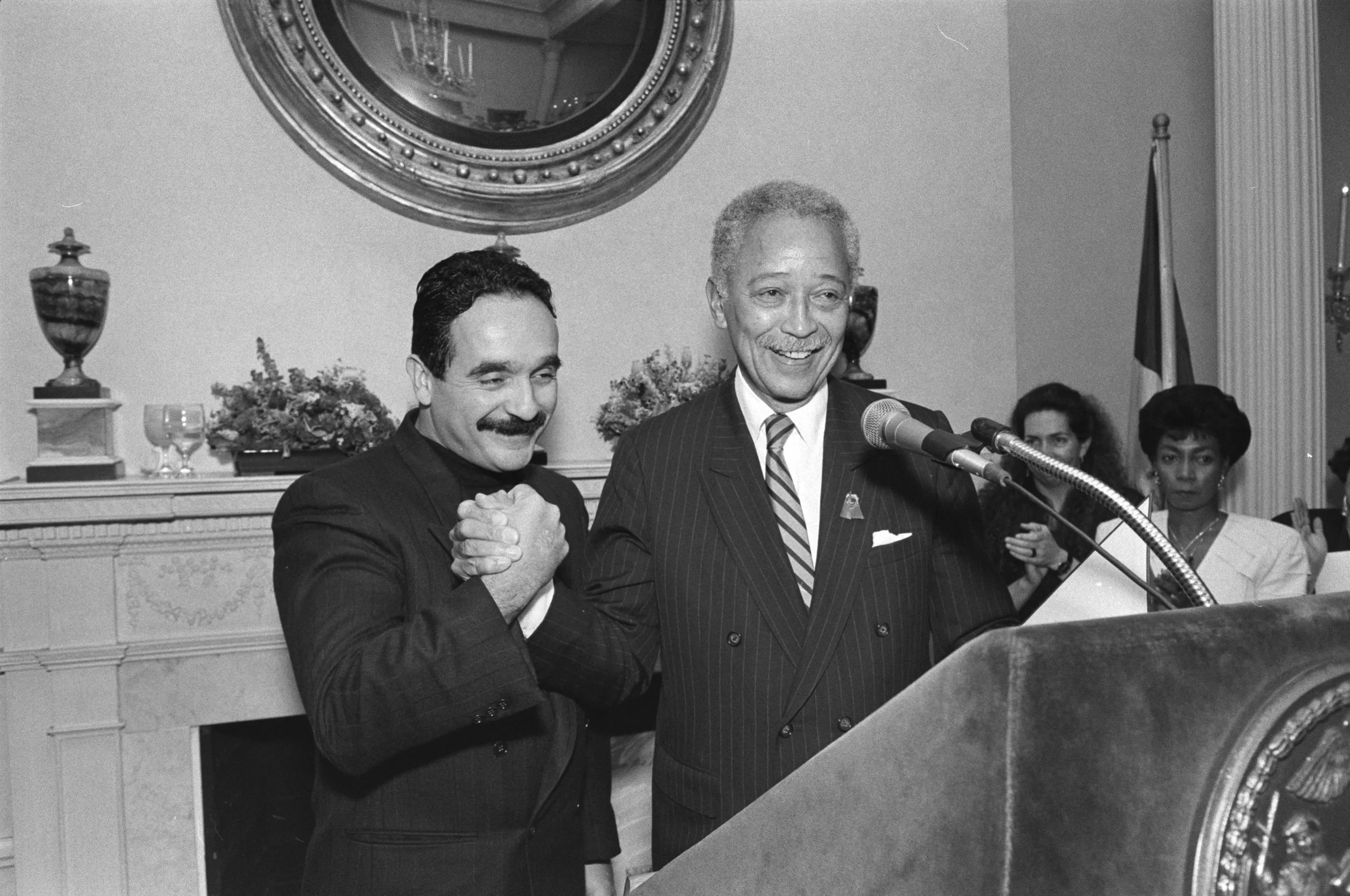

In the early 1990s, Colón served as a special advisor to Democratic Mayor David Dinkins, appearing with him in numerous events, parades, and press conferences.

Mayor David Dinkins and Willie Colón, City Hall, November 16, 1990. Mayor David Dinkins Photograph Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

A New York Times article in June of 1994 describes Willie’s transition into full-time politics owing to his observance of “disturbing trends.” He identified “a regression in race relations, misplaced government priorities like cutting back schools and social programs while spending billions in foreign aid” (NY Times, 1994). As result, Colón tried his own hand at electoral politics. In 1994 he unsuccessfully ran as a Democratic candidate for New York Congress. He tried and lost again in the 2001 election for New York Public Advocate. In 2014, Colón graduated from Westchester County Police Academy and was sworn in as a Deputy Sheriff for the Department of Public Safety.

Mayor David Dinkins presents the Certificate of Recognition to Willie Colón, City Hall, November 16, 1990. Mayor David Dinkins Photograph Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Later in his life, Colón switched from endorsing Democratic candidates like Hillary Clinton to voting for Donald Trump in 2016. He remained a vocal Republican until his passing in Bronxville, New York, on February 21, 2026. He was 75 years old.

Willie Colón was a New Yorker through and through. This blog illuminates the numerous examples of his legacy found in the NYC Municipal Archives; one can only assume that there is far more to discover about the ways he influenced New York City and the world.

Willie Colón & Hector Lavoe – “Che Che Cole” Live/En Vivo, Fania Records, circa 1971.

“Salsa is not a rhythm. Salsa is a concept. It’s an inclusion and a reconciliation of all the things that we are, here in the Bronx and the music that we make together.”

—Willie Colón