On June 12, 2022, after a two- year hiatus due to COVID, New York City will host the 65th National Puerto Rican Day parade. This week, For the Record will feature a resource available in the Municipal Archives to research the history of Puerto Ricans in New York City. The focus is on the extensive Board of Education collection.

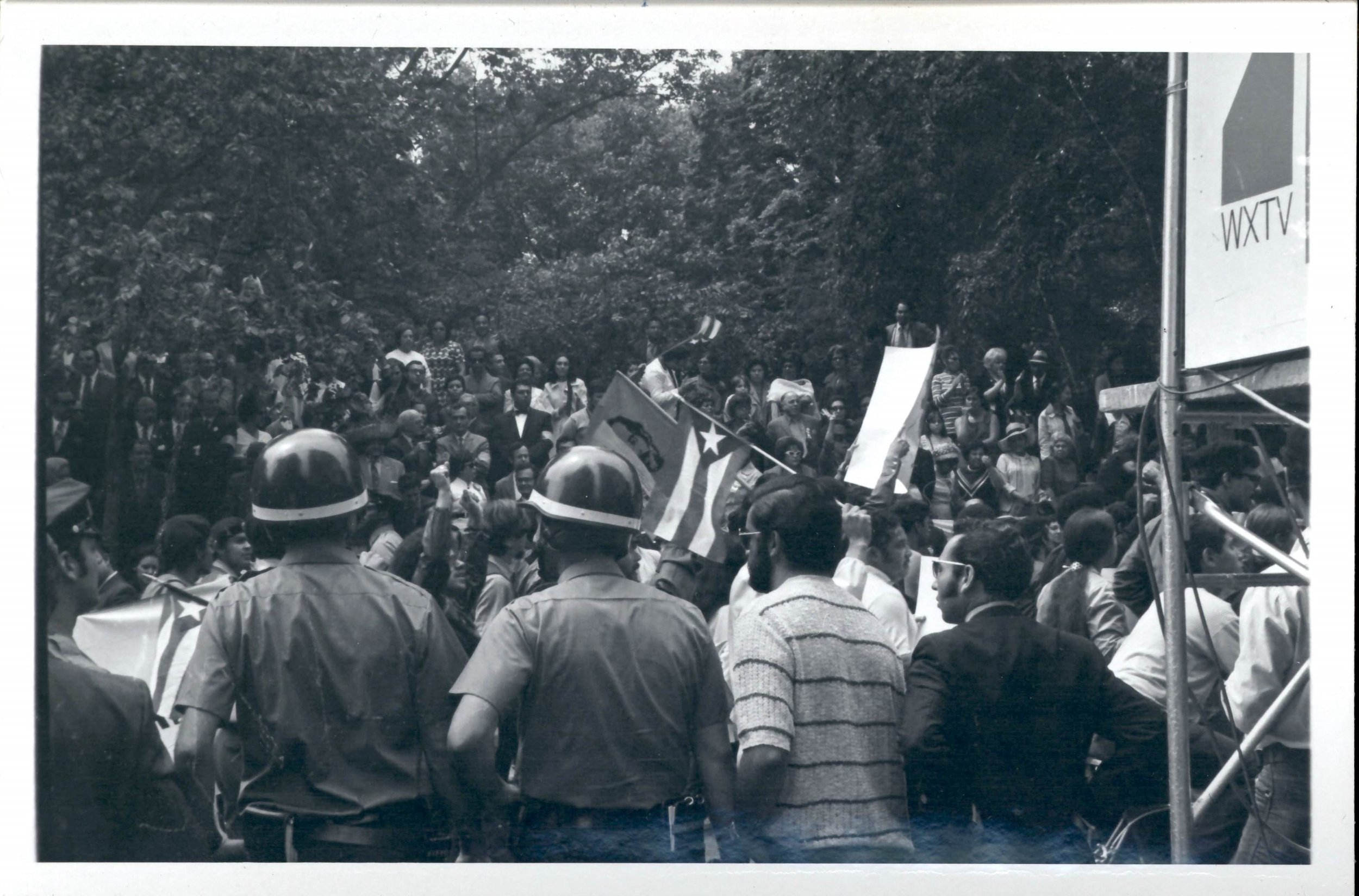

Puerto Rican Day Parade, June 7, 1970. NYPD Special Investigations Unit photograph collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

In the 1950s, the advent of air travel enabled many Puerto Rican families to move to New York City. The new immigrants impacted numerous aspects of New York City. Faced with this big population, many of whom spoke little to no English, the leaders of the City’s school system realized they needed to create programs to help the children of the new residents.

One program established by the Board of Education was called the Puerto Rican Study. It was created to develop policies, curricula, and programs for the increasing number of students arriving from Puerto Rico. At three and a half cubic feet, the Puerto Rican Study collection is filled with draft letters, general correspondence, reports and subject files all detailing the different ways the study impacted newly arrived Puerto Rican children and, on a broader scale, the New York City school system itself.

The collection, housed at the Archives’ Chambers Street location, is a treasure trove of resources about this lesser-known aspect of NYC Puerto Rican history. The first half of the collection contains early drafts of reports and studies, as well as correspondence, including a letter from Mayor Robert Wagner concerning the Committee on Puerto Rican Affairs and the Mayor’s Commission on Inter-Group Relations.

Mayor Wagner to Dr. Clare C. Baldwin, Assistant Superintendent of Schools, page 1 of 2, January 6, 1956. Board of Education collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Mayor Wagner to Dr. Clare C. Baldwin, Assistant Superintendent of Schools, page 2 of 2, January 6, 1956. Board of Education collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The second half is filled with curriculum notes and reports. The curricula were extensive and detailed; there are series titled Resource Unit, Language Guide and other related materials.

Curriculum Materials Prepared by the Puerto Rican Study, 1956-1957. Board of Education Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The resource units were based on New York City social studies guides but were intended to help teachers in classes with pupils who were recent arrivals from Puerto Rico. These resource units were organized by themes designed to help Puerto Rican students appreciate and assimilate into American culture. Examples of potential assignments included visiting the Statue of Liberty and “playing musical instruments found in Puerto Rico: maracas, guitar.” Below is an example of some of the resource unit themes:

Resource Unit, 6th Grade, cover. Board of Education collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

There were also units created to teach map skills, as well as how to appreciate technology designed to make life easier. The map skills assignments were connected to United States history, with examples such as having students locate Georgia, and then relate this knowledge to Eli Whitney and the cotton gin. The general theme of these resource units was to provide students the life skills to live in New York City and, more broadly, the United States itself. Other topics included transportation, how to navigate the subway system, and learning how to use a telephone. All of these were designed to create a group of students that could fully assimilate into American culture.

The Puerto Rican Study resulted in a large, bound comprehensive report covering the years 1953 to 1957, published in 1958 by the Board of Education.

The Puerto Rican Study, 1953-1957, cover. Board of Education collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The Puerto Rican Study, 1953-1957, table of contents. Board of Education collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The book, The Puerto Rican Study defines itself as a “four-year inquiry into the education and adjustment of Puerto Rican pupils in the public schools of the City of New York.” On a macro level, it describes school authorities’ efforts to “establish on a sound basis a city-wide program for the continuing improvement of the educational opportunities of all non-English-speaking pupils in the public schools.”

Resource Unit, Theme 3, Transportation. Board of Education collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Did the Puerto Rican Study succeed? As a study, it never claimed to be able to solve the “Puerto Rican problem,” but it did succeed in bringing a level of awareness to the task of assimilating non-English speakers in public school systems in a way that had never been done before. Reviewing the report and related documents in the Municipal Archives collection highlights the thought and effort put into the report, as well as providing numerous examples of the way the project was implemented.

Puerto Ricans established themselves as a major and permanent part of New York City, and with the Puerto Rican Study, the future of those Puerto Rican children seemed brighter. According to the 2010 Census, Puerto Ricans make up 8.9 percent of the population of New York, and it is the state with the highest population of Puerto Ricans. The history of Puerto Ricans in New York City can be found everywhere in the Municipal Archives—from the NYPD surveillance collection to the mayoral collections. The Board of Education collection, and specifically the Puerto Rican Study, is simply one small part in a broader story, one that I, as a fellow Puerto Rican, am excited to keep celebrating.