This past May For the Record introduced a new project Processing and Digitizing Records of the New York City Commission on Human Rights. Supported by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission of the National Archives as part of their Documenting Democracy initiative, the project will enhance public access to records created by the New York City Commission on Human Rights. Key activities of the project include rehousing and processing 268 cubic feet of records, digitizing the earliest 53 cubic feet, publishing digitized materials, an online finding aid, social media content and blog posts, and curating a digital exhibit that showcases both the collection and the project’s progress.

This 1964 flyer is from grassroots organizing efforts to end segregation in New York City’s public schools. NYC Commission on Human Rights collection: REC0103, Box: 59, Folder: 17. NYC Municipal Archives.

This week, project staff discuss the historical background of the human rights movement and how the records in the CCHR collection tell the story. Several items identified during processing serve to illustrate this important historical trajectory.

In 1943 Mayor LaGuardia established The Mayor’s Committee on Unity, the first New York City municipal government entity created specifically to address racial and religious tensions and discrimination. The Committee investigated discrimination, mediated community disputes, and produced reports on issues such as inequities in education and city services. Its leadership and membership reflected the city’s diverse communities, and its research was widely circulated to government agencies, universities, and civil rights organizations.

Community members frequently brought neighborhood concerns directly to the Mayor’s Committee on Unity; especially complex or ongoing issues were assigned to subcommittees. For example, the Subcommittee on City Services in Congested Areas investigated inequities in sanitation services within densely-populated minority neighborhoods, while the Subcommittee on Press Treatment of Minority Groups worked with local newspapers to encourage adoption of fair and non-discriminatory news coverage protocols.

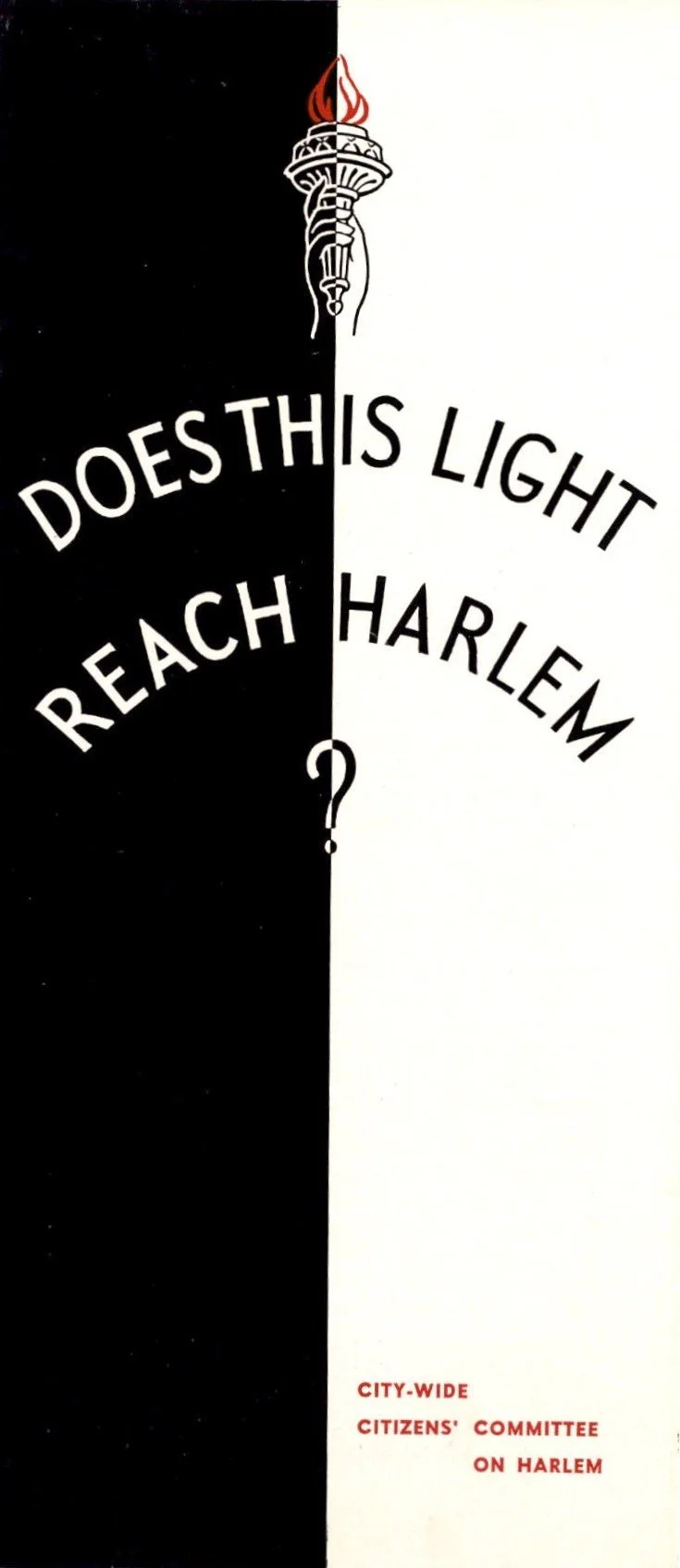

This 1944 pamphlet was published by the City-Wide Citizens’ Committee on Harlem, another early civil rights organization that worked with the Mayor’s Committee on Unity to address inequities facing Harlem residents during the mid-20th century. NYC Commission on Human Rights collection: REC0103, Box 25, Folder 5. NYC Municipal Archives.

Long before Mayor LaGuardia established the Unity Committee, specifically dedicated to human and civil rights, several organizations laid the groundwork for addressing institutional discrimination and the need for change. A few organizations that influenced the debate and worked with the City government are shown below.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909, held its first meeting in New York City. They came into being after the 1908 Springfield Race Riot in Illinois. Accounts of mobs terrorizing the town, lynching Black citizens and burning homes and businesses shocked the nation. The first national organization formed to fight for the rights of Black Americans, the NAACP interracial membership included the Black writers and activists W.E.B. Du Bois and Ida B. Wells-Barnett. They led national campaigns against lynching and segregation, advanced rights through strategic litigation (culminating in victories like Brown v. Board of Education), and built sustained public advocacy for racial equality in the United States.

in 1913, the B’nai B’rith, a Jewish fraternal organization, founded the Anti-Defamation League to combat antisemitism and fight for civil rights for all marginalized groups in the United States. Members monitored extremist groups like the KKK, fought against discriminatory hiring practices, and promoted civil rights legislation.

In 1942, a group of interracial students in Chicago organized the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). They were inspired by methods of non-violent protest and applied those tactics to help end segregation and discrimination in the United States through sit-ins, voter registration drives, and numerous de-segregation campaigns.

1947 cartoon strip, “Hopeless Henry” by Kaulee. Produced in the aftermath of World War II, the strip was designed to build public support for the newly formed United Nations while also challenging discriminatory attitudes at home. NYC Commission on Human Rights collection: REC0103, Box: 44, Folder: 9. NYC Municipal Archives.

During WW II, Americans heavily promoted the idea that they were fighting for democracy, freedom, and the dignity of all people. There was a strong cultural understanding of the dichotomy “Democracy vs. Fascism.” This idea strengthened changing attitudes towards the necessity of human and civil rights, not just in the war effort, but in the U.S. as well. The 1940’s were still a deeply racially segregated era in the U.S., but northern urban centers, especially New York City, Chicago, and Detroit were some of the first to reach beyond the concept of individualized racism and start addressing structural racism within localized urban contexts.

This 1951 report reflects city government’s engagement with the moral challenges of segregation and efforts to confront and change those conditions. It also demonstrates the influence of ideals shaped by World War II and the emerging international human rights framework established by the United Nations. NYC Commission on Human Rights collection: REC0103, Box: 38, Folder: 11. NYC Municipal Archives.

The United Nations established Human Rights Day in 1950 to celebrate the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Adopted on December 10, 1948, the Declaration is the first global statement of fundamental human rights. In recognition of this occasion, it is valuable to consider how national and international human rights discourse in the latter half of the twentieth century shaped the work of New York City government.

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka Kansas, declared “. . . in the field of public education, the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. The American Civil Rights Movement gained momentum after the Brown vs. Board of Education decision. In 1957, the City’s Unity Committee evolved into a permanent city-funded agency, the Commission on Intergroup Relations.

Cover sheet from a 1963 research study conducted by the Greater Urban League of New York on the “Problems of Integration in New York City Public School since 1955.” The study was used to guide the City Commission on Human Rights plan of action to more comprehensively tackle desegregation. NYC Commission on Human Rights collection: REC0103, Box: 60, Folder: 7. NYC Municipal Archives.

Events around the country during this period, ranging from the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955, integration of the Little Rock Central High School, the March on Washington and passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, all contributed to a greater awareness of discrimination. While New York had made attempts to address school segregation prior to the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, progress was slow and uneven. By 1964, frustration over these delays led to a series of massive school boycotts co-organized by the NAACP, the Harlem Parents Committee, CORE, PACE, and the Pan Hellenic Council. About 45% of all NYC students boycotted school on February 3, 1964. An estimated 464,361 students and teachers participated overall, the boycott being so large that it exceeded the number of people who took part in the March on Washington.

Established in 1957, the Commission on Intergroup Relations had a broad mandate, but it created fewer records than the earlier Committee on Unity, and its successor organization, the City Commission on Human Rights. It could be argued that the committee was struggling to keep pace with a rapidly shifting social landscape, resulting in record-keeping practices and organizational structures that were less robust than usual.

In 1962, the Commission on Human Rights took over this role and the administrative records reveal a complex engagement with civil rights issues, activist groups, and civil rights leaders of that time. The first executive director of the Commission on Human Rights, Madison Jones, was the point person for all civil rights issues relayed from the Mayor’s office, as evidenced in the records of their frequent correspondence. A large part of the administrative records also deals with the desegregation of NYC schools. Materials found in the series include reports, action plans, data, press releases, and boycott responses. The CCHR was definitely aware of, and in conversation with, civil rights activist groups and civil rights leaders—there are references and mentions of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X in the records.

This excerpt from a 1962 letter written to Madison Jones, the executive director of the City Commission on Human Rights inquires if Jones had invited Malcolm X to the 1962 Harlem Leaders Conference, an interesting piece of ephemera showing the dialogue happening in the NYC government regarding prominent civil rights leaders. NYC Commission on Human Rights collection: REC0103, Box: 61, Folder: 31.

The relationship between CCHR and the political discourse of the time seemed to shift in nature, to that of response, as opposed to the early Mayor’s Committee on Unity’s work, which was more preemptive and forward-looking. But the political discourse around human rights was also very different in the 1940’s compared to the 1960’s, which could partly account for the change in the Commission’s programmatic planning. The archival records suggest that it was the activist groups who pushed for the changes that the city government then responded to, and the city government was often targeted and criticized for its seeming indifference due to its slow bureaucratic processes in making the changes. It would certainly be an interesting research topic to study how the city government’s actions changed, how the political landscape changed, and how the public’s attitudes towards the city government changed when reflecting on civil rights issues from the 1940’s-1960’s.

This summary of negotiations regarding a discriminatory rental practice at the Electchester Housing Cooperative was found amongst correspondence sent from CCHR executive director Madison Jones to the Mayor’s Office. It’s important to note that two local branches of the NAACP and the American Jewish Congress, another civil rights activist group, were part of the negotiations, showing further dialogue between the city government and civil rights activist groups. NYC Commission on Human Rights collection: REC0103, Box: 60, Folder: 28. NYC Municipal Archives.

Current City Organizations Dealing with Human Rights

Since the 1960’s there have been continual changes in the discourse on human rights and in the City’s response to these issues. Several commissions and offices addressing these intersectional concerns have been established, in addition to the CCHR. The City established the Equal Employment Practices Commission in 1989 through the Charter.

In 2022, voters passed an amendment to the City Charter establishing the Mayor’s Office of Equity and Racial Justice. It is comprised of several governmental offices and commissions that bring an intersectional approach to equity, including NYC Her Future (NHF), the NYC Commission on Gender Equity (CGE), the NYC Unity Project (UP), and the NYC Young Men’s Initiative (YMI) as well as multi-agency bodies like the NYC Pay Equity Cabinet (PEC) and the NYC Taskforce on Racial Inclusion & Equity (TRIE). Together, these offices and commissions aim to engage New York City’s diverse communities and constituencies, advance equity and promote racial justice within New York City.

The City Commission on Human Rights has continued operating under the same name from 1962 until today. The passage of the Human Rights Law of the City of New York in 1965 gave the CCHR authority to prosecute discrimination in private housing, employment, education, and public accommodations. These demanding and important aspects of the CCHR’s work, continues until today. Currently, the CCHR also promotes education on human rights issues through outreach programs and restorative justice practices at community service centers throughout the boroughs.

Conclusion

This dynamic evolution of the concept of human rights has left important evidence in the archival records of New York City’s government. The City Commission on Human Rights Collection offers a concrete, detailed look into the history of a municipal government’s engagement with the fight for human rights, its categorizations, communications, methodologies, applications of the law, and both its achievements and shortcomings confined to the practice of a single city’s governance, from the 1940’s until today.

Sources

Timeline of the American Civil Rights Movement- Encyclopedia Britannica

Stryker, S. (2017). Transgender history: The roots of today’s revolution. Seal Press.

Federal support for Documenting Democracy was provided by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission of the National Archives.