If you’ve communicated in writing to a government official, chances are good that you received a generic, somewhat non-committal response. Frequently the response is a form letter sent to every other person who raised the same issue. That is the standard operating procedure and has been for decades.

Interborough Rapid Transit, Contact 2. Illustration from Silver Connections, A Fresh Perspective on the New York Area Subway Systems, Volume III, by Philip Ashforth Coppola, 1994. Municipal Library.

That was not always the case. Take, for example, Mayor William J. Gaynor’s correspondence with sundry New Yorkers. Gaynor was elected mayor in 1909 and served until 1913, when he died from complications related to an assassination attempt three years prior. His previous service as an Appellate Judge in New York’s Second Department, apparently did not confer upon him the so-called “judicial temperament.” Initially nominated by Tammany Hall, Gaynor split from the machine and launched an independent campaign for reelection. Prior to the 1913 election, he passed away while on a trip to Europe.

Mayor Gaynor may be known for many things: surviving an assassination attempt and rejecting Tammany Hall’s guidance. But, he was not known for being reticent or mealy mouthed. His correspondence with sundry New Yorkers offers proof of impolitic, perhaps even rude, responses to suggestions, inquiries and other mail. Each of the responses is specific, unique and very pointed. The missives are carbon copies of typed letters dictated by the Mayor that are preserved on very transparent paper called onion skin.

On March 16,1910, Gaynor responded to a request for a contribution from the New York Anti-Saloon League with a resounding rejection. “I beg to say in answer to your letter of March 11th that I cannot subscribe $10 for a box and I think it very bad taste to ask me to do so. If I gave money in response to all the similar calls that are made on me I would be bankrupt in short order, and it is strange to me that there are so many people who do not know better than to ask me for money.”

Correspondence, July 2, 1913, onion-skin. Mayor William Gaynor Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

On June 30, 1911, he wrote a pithy note to a representative of the First Mortgage Guarantee Company. “It is useless to send registered letters to my house. I am there only during the night. I do not receive registered letters and will not do so. Such caution is very troublesome and wholly unnecessary in my judgment.”

Gaynor was supportive of organized labor and there are several notes to City Commissioners reminding them to use union labor. He struck a somewhat different tone in a letter to a New York Union Printer named John S. Lewis in 1913. “My views about Union labor are too well known to need to be repeated at this time. If you had kept track of things you must know that. I do not believe in people beginning to talk about how much they are in favor of Union labor about election time. Acts count for more than words. Such talk when an election is coming on is cheap.”

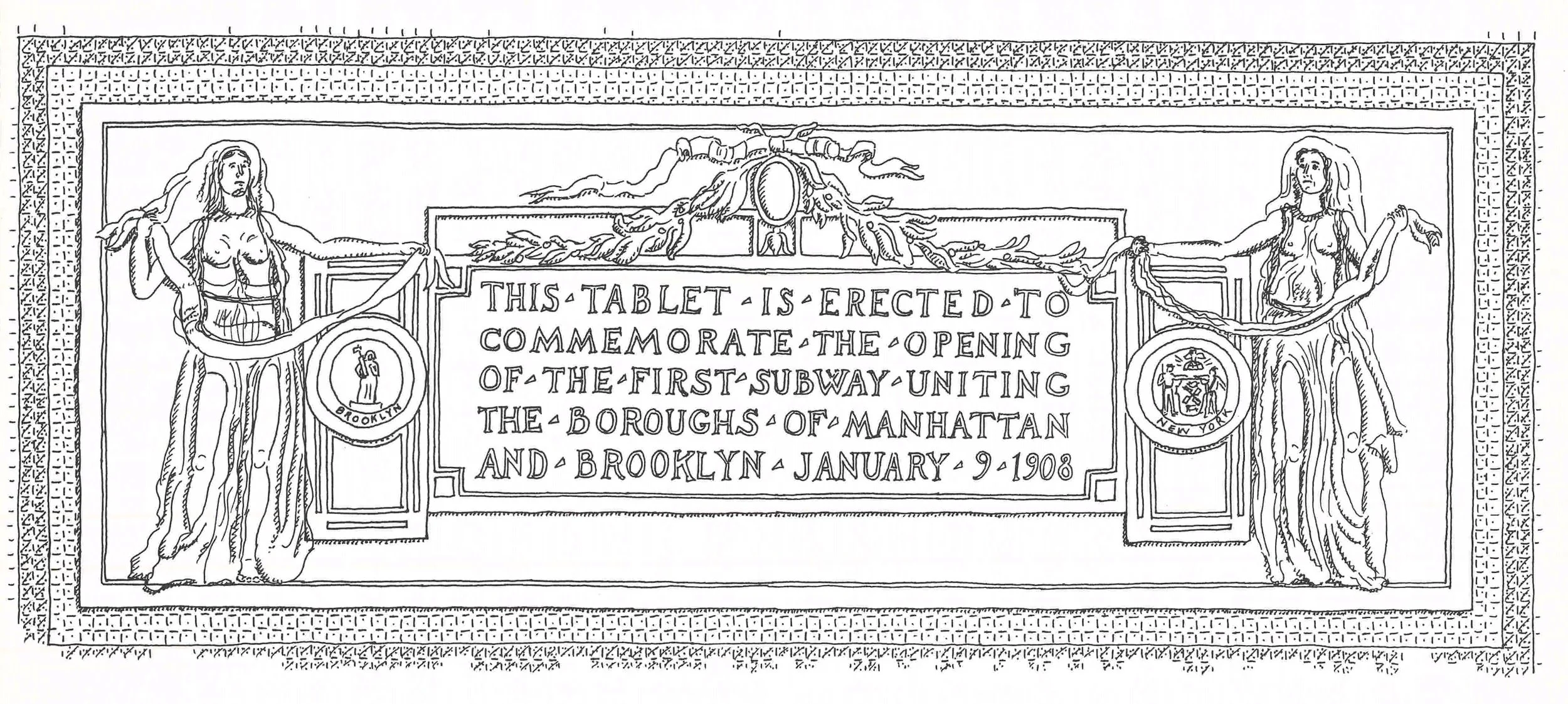

Tablet. Illustration from Silver Connections, A Fresh Perspective on the New York Area Subway Systems, Volume III, by Philip Ashforth Coppola, 1994. Municipal Library.

New York State law prohibited public games, liquor consumption and selling food on Sundays, in deference to a Christian belief that this was a day of rest. The Mayor received various notes from people complaining about ball playing on Sunday. He was, characteristically, unsympathetic. To the Reverend Joseph Keevil of Brooklyn he wrote a long response. It began, “Your letter of July 17 is at hand. You advise me of an opinion of the Attorney General on baseball playing on Sunday. The opinion adds nothing new to the legal question. You also say to me as follows: “In the light of this decision it is clear many of the baseball games played in this city every Sunday is in clear violation of the law.”

You add as follows: “We do most respectfully request you to enforce the law.”

“It may be I should correct your inadvertent mistakes of grammar and spelling, but I hesitate to take that liberty.

I do not know of any illegal ball game, golf game or any other game being played in this city on Sunday. You specify none. You only say generally that many of them are in violation of the law and that it is a disgrace to the city. If you know of any you ought to specify it to me if you want me to help prosecute the offenders.”

I.R.T. Contract #2, Brooklyn, 1908. Tablet. Illustration from Silver Connections, A Fresh Perspective on the New York Area Subway Systems, Volume III, by Philip Ashforth Coppola, 1994. Municipal Library.

During his term, the City was considering building more subway lines and expanding those that existed. There was a policy debate around expanding the existing Interborough system versus establishing a new TriBorough system and whether the City or private operators would manage the systems. Several folders of correspondence attest to the significance of the matter, which was not resolved during Gaynor’s term.

The South Side Board of Trade, a group of Bath Beach businessmen, sent a lengthy letter supporting construction of the Triborough route and cited Gaynor’s campaign statements in support of building more subway systems. The Mayor responded with a lengthy letter in which he acknowledged support for building subways and disavowed support for the Triborough. “Your notion that I ever made any pledge to build the tri-borough route has not a leg to stand on…. I do not think that you know enough on the subject to say how you would vote if you were in my place… What you do not know about this subway situation would fill a book…”

On November 21, 1910, Gaynor signed a letter he had dictated for assistants to type, addressed to a Mr. Kraft who had questioned a proposed subway expansion. Gaynor posed several questions: “What is the tri-borough route which you mention? Do you know where it runs, how much it would cost and how long it would take to build? Do you know how much available credit the city has to devote to subways? In a word do you know anything on the subject at all? Of course you understand that I have to deal with facts and not with more talk. Begin to think a little yourself, and study the maps, and study the city’s credit, and pay less attention to sensational newspapers. You ought to have opinions of your own if you are an intelligent man.”

Then, as now, elected officials sparred with the media. In Gaynor’s case, the nemesis was The New York Journal owned by Randolph Hearst. In multiple letters he wrote that the correspondent was deceived by evil publications. For example, a January 31, 1911, response to a J. S. Mencken, Esq, he wrote, “Your letter of no date is at hand. You are very grievously misinformed. I am breaking no promise that I ever made with regard to subways. I think you are reading some lying newspaper.”

As a vote neared at the Board of Estimate, the Chamber of Commerce and the Merchants’ Association proposed establishing a Citizen’s Committee to review the subway proposals and produce a report that would “assist the public to a clear understanding of the several alternative propositions which are pending, and to crystalize public opinion and sentiment in favor of some definite solution of the problem. The public is intensely interested, but at present is hopelessly confused and uncertain as to what should be done,” wrote the President of the Merchants’ Association to Seth Low. Low had served as the Mayor of both the independent City of Brooklyn and the consolidated City of New York. He was to be the Chair of this committee. Even this seemingly routine event provoked an irascible response from the Mayor. First, he wrote to the associations that he had nor requested the committee be created. “I did not request that it be done. On the contrary, you approached me with the suggestion that it be done and I acquiesced in it.”

During the month of December, 1910, the committee met, reviewed the relevant expert documentation, financial notes and official testimony and issued a summary report at the end of the month. This prompted Mayor Gaynor to send a laudatory thank you letter to former Mayor Low. “ I had not supposed it possible to compress so much work into so short a space of time. The comprehensive character of the reports cannot fail to be of great service to this community and to public officials. That such a body of men should devote days of continuous work to the study of this difficult problem of subways is another proof that we have many among us who have at heart the public weal and comfort above all else.”

And then, as if he couldn’t contain himself, he nitpicked. “I note that you open your report by the statement that the committee was appointed at my request. This is an error. It was done at the request of…. They made the suggestion to me that they would like to proceed to do so, and asked if it would be agreeable to the Mayor. Of course I acquiesced but I am not entitled to the credit of having suggested or requested the appointment of the committee. Let credit go where it belongs.” This was a point he had addressed with Low in early December and somehow it disturbed Gaynor greatly that the committee was attributed to him.

Low, though, was not one to back down. The former mayor replied to Gaynor, “I did not forget, of course, what you said to me in regard to the appointment of the Committee: but, inasmuch as Mr. Hepburn and Mr. Towne in their letter of appointment used the expression that the Committee had been appointed at your request, I thought that it was legitimate to assume that, while the idea had not originated with you the action taken was, nevertheless, at your request. I am hoping that you welcome, rather than otherwise, the opportunity which my letter gave to you to make clear publicly your relation to the matter.”

That seems to have ended the matter. In late January, Mayor Gaynor wrote a note of appreciation to the head of the Merchants’ Association, Henry R. Towne that perfectly illustrates his directness. “I have at last found time to read the report of your special committee on the question of competition of public service corporations and regard it as very able and timely. But what is the use in having men among us who understand things so well, if we elect men to office who do not know the A.B.C. of the matter and throw the whole thing to the winds? How quick such a committee would dispose of the subway matter wisely and well, and without allowing any right or advantage of the city to be lost or thrown away.”

William J. Gaynor died at age 65 on September 10, 1913. In 1926, Mayor James J. Walker presided over a ceremony dedicating a monument to the late Mayor on the Brooklyn approach to the Manhattan Bridge, May 12, 1926. Photographer: Eugene deSalignac. Department of Bridges Plant & Structures Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Mayor Gaynor’s correspondence has been the subject of previous For the Record articles. Readers are invited to continue enjoying his writing style in The Pleasures and Profits of Walking, A False Police Report on a Boys Arrest, Mayor Gaynor and Children in the City.