The New York City Health Department has been keeping New Yorkers healthy for 220 years. Their anniversary provides For the Record an opportunity to discuss some of the many collections in the Municipal Archives with materials relevant to public health research topics.

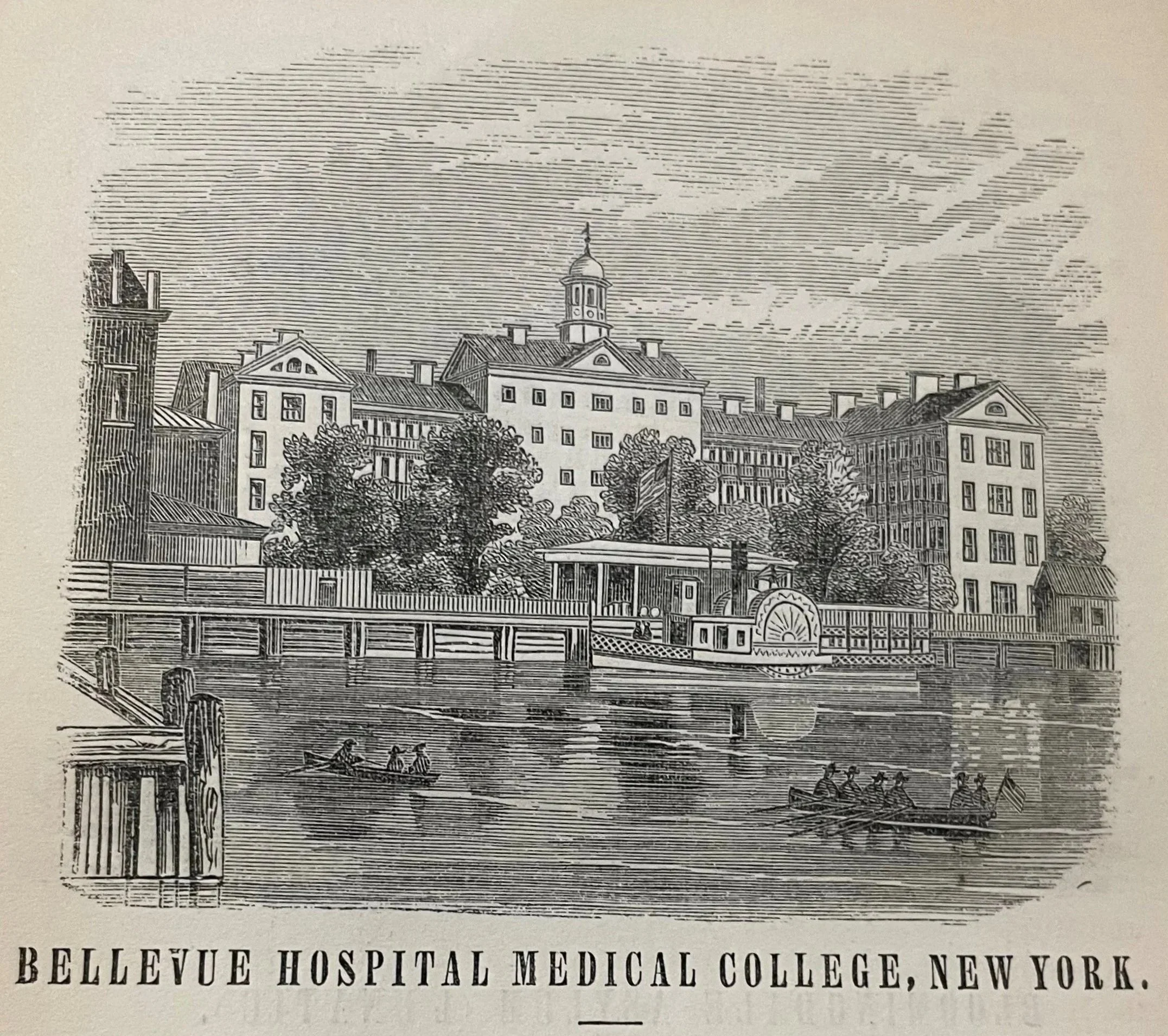

Bellevue Hospital, 1862, engraving, Valentine’s Manual, 1864. Municipal Library.

““Mrs. Baisley in Moore Street, has lost her husband and three children to the prevailing fever,…””

The Health Department traces its origins to January 17, 1805, when the Common Council passed a law “for the establishment of a Board of Health, and for the appointment of a City Inspector.” The legislators took this action in response to a yellow-fever epidemic then raging through the City.

However, “health” as a concern of local government officials long pre-dates this legislation. Collections in the Municipal Archives document issues related to the health of city inhabitants as far back as the first Dutch colonial settlement. The printed, published proceedings of the legislative bodies—Records of New Amsterdam, 1653-1674; Minutes of the Common Council 1675-1776; and Minutes of the Common Council 1684-1831—provide useful entry points to identify health-related references.

An entry in the New Amsterdam Records from 1664, describes how two homeowners feared a tannery “established between their houses...” will spoil their water and “...they shall also have to endure great stench from the tanning of skins.” The Burgomasters and Schepens declined to ban the tannery saying that “as others have been allowed to make a tannery behind their house and lot, such cannot be forbidden.” The indexes to the Records and Minutes provides dozens of citations to similar and continuing matters related to public health.

Resolution from the Common Council that no persons from Philadelphia shall come to this City, 1793. Common Council Records, NYC Municipal Archives.

In addition to the printed and published Minutes of the Common Council, the Municipal Archives maintains a separate collection of records created or received by the legislative bodies. The series spans 1670 to 1831. The documents, mostly petitions, resolutions, financial documents, and correspondence, are arranged chronologically. After 1800 the arrangement is further refined by the “committees” established by the Council, e.g. finance, roads, etc.

The first “Health” labeled folder dates from 1793. It comprises documents that the Council referred to a Committee they appointed to prevent the introduction and spread of infectious diseases. The eight documents in the 1793 folder all address news of a yellow-fever epidemic in Philadelphia: “The Corporation of this City having this day resolved that no person coming from Philadelphia shall come into the city. I am directed by the Committee … to inform all passengers in the stages from Philadelphia that they will not be suffered to land here.” (September 16, 1793.) It is not clear from the folder contents whether the Council ever formally lifted the ban on visitors from Philadelphia.

“September 8th, 1803: The Health Committee met pursuant to adjournment. Present his Hon. The Mayor, Chairman; the recorder; Aldermen Vanzandt, Bogert, Ritter, Barker, Minthorn.

Dr. Rodgers and Miller attended nine deaths and twenty new cases of malignant fever occurred the last 24 hours. Mr. James Hardie reported six internments in the church burial grounds inclusive of one included among the fever deaths and two were buried at Potters Field not of fever making the mortality for the last 24 hours – Seventeen. Committee adjourned to 9th Sept.” Department of Health book, 1790 -1803. NYC Municipal Archives.

“The number of persons, interred in each of the Burying Grounds of this City, from the first of August, to the tenth of November 1790.” Department of Health book, 1790 -1803. NYC Municipal Archives.

The Council-appointed Health Committee kept written minutes or proceedings of their meetings. Maintained as a separate collection in the Archives, the first extant volume of the Committee minutes is dated September 10 - December 11, 1798. The entries begin with routine business, e.g. payments for nursing services, procuring supplies, and “... a suitable carriage for the removal of the sick from this City to Bellevue [hospital].” The Committee also “Resolved that Doctors Alexander Anderson and Charles McLean be appointed to attend the sick poor in this City and report their situations from time to time to this Committee.”

““Doctor Benjamin Hicks reports Montgomery Miller, Read[e] Street two doors down from the corner of Church Street right hand side, is in the last stage of the fever, in want of necessaries….””

The Minutes then record dozens of reported “situations” such as, “Mrs. Waters of No. 288 Water Street is reported to [be] ill with the prevailing fever and in want of necessaries.” “Margaret Ireland of Henry Street has a family of four children in distress—gave her three dollars.” And, “Catharine and Mary Condon, orphan children, there [sic] mother died in Orange Street some twelve days ago, received into the Almshouse.” The volume includes a name index, and an appendix listing the “Burials in the different grave yards in the City, at Potter’s Field & Bellevue, from 8 August to 12 November 1798.” The Minutes series continue through, the nineteenth century, but with significant gaps.

The Historical Vital Records Collection

One important function of the Health Department, the creation of vital records, is of particular significance to Municipal Archives patrons. Beginning in the 1950s, the Health Department began transferring their older vital records, both ledger-format and certificates, to the Municipal Archives for public access. Now totaling more than 13 million birth, death and marriage records, the collection has served generations of family historians.

““Susannah Allen represents, that she has seven small children, lost her husband about two months ago,… gave her three dollars….””

The oldest record in the series is a list of yellow fever victims during 1795 in Manhattan. In 1801, and again in 1804, the Common Council addressed record-keeping related to deaths. Notably, in 1804, the Council specified that the “Inspector . . .cause to be published… an accurate list of the deaths of the preceding week with the age sex disease and other particulars of each person so dying and where buried. And shall keep a register wherein he shall record the names of all persons returned as aforesaid which shall be open during office hours to the inspection and examination of any person who may or request a view.”

Among justifications in the 1804 directive for vital record-keeping, the Council said that it would be necessary “...to enable posterity to prove the decease of their ancestors, relatives and connections.” And indeed, posterity has greatly benefited from their action. In Fiscal 2025, the Municipal Archives supplied more than 15,000 copies of vital records to its patrons.

““Sarah Frygill, represents that Joseph a free Black lays ill in her cellar No. 28 Roosevelt Street, in want of medical aid….””

In 1866, the New York State legislature passed a public health law that established the Metropolitan Board of Health, the first municipal public health authority in the U.S. Four years later, the State passed another law that created the Department of Health for the City of New York, with a new Board of Health operating as its overseeing body. Researchers interested in documenting the evolution of these entities as they grew to become pioneers and leaders in public health will find ample source material throughout the mayoral records. Beginning with the administration of Mayor Van Wyck in 1898, clerks maintained “Departmental Correspondence” as a separate series providing quick access to Health Department actions. The mayor’s subject files are also a gold mine of information.

““William Gardner, Hezekiah Read, and Maysey a Black woman opposite Daniel Dunscomb’s in Pearl Street in want of everything will pay for a nurse,— Doctor McLean will attend them….””

Researchers focused on the twentieth century will find an abundance of relevant material for health topics. The most comprehensive collection is the Health Commissioners records. Processed with support from the National Endowment for the Humanities in 2017, the collection totals 742 cubic feet and spans 1928 to 1991. The records document the Department’s wide-ranging responsibilities and actions such as regulating the milk supply, vaccinating the city against polio, tackling drug addiction and sexually-transmitted diseases, and improving maternal and child health. There is a wealth of correspondence about polio, the AIDS crisis, the administration of city health clinics, and Medicaid.

The foregoing description of health-related materials in the Archives is only the “tip of the iceberg,” to use a cliche. Researchers are invited to use the Collection Guides to learn about the dozens of Health Department-created or related collections in the Archives.

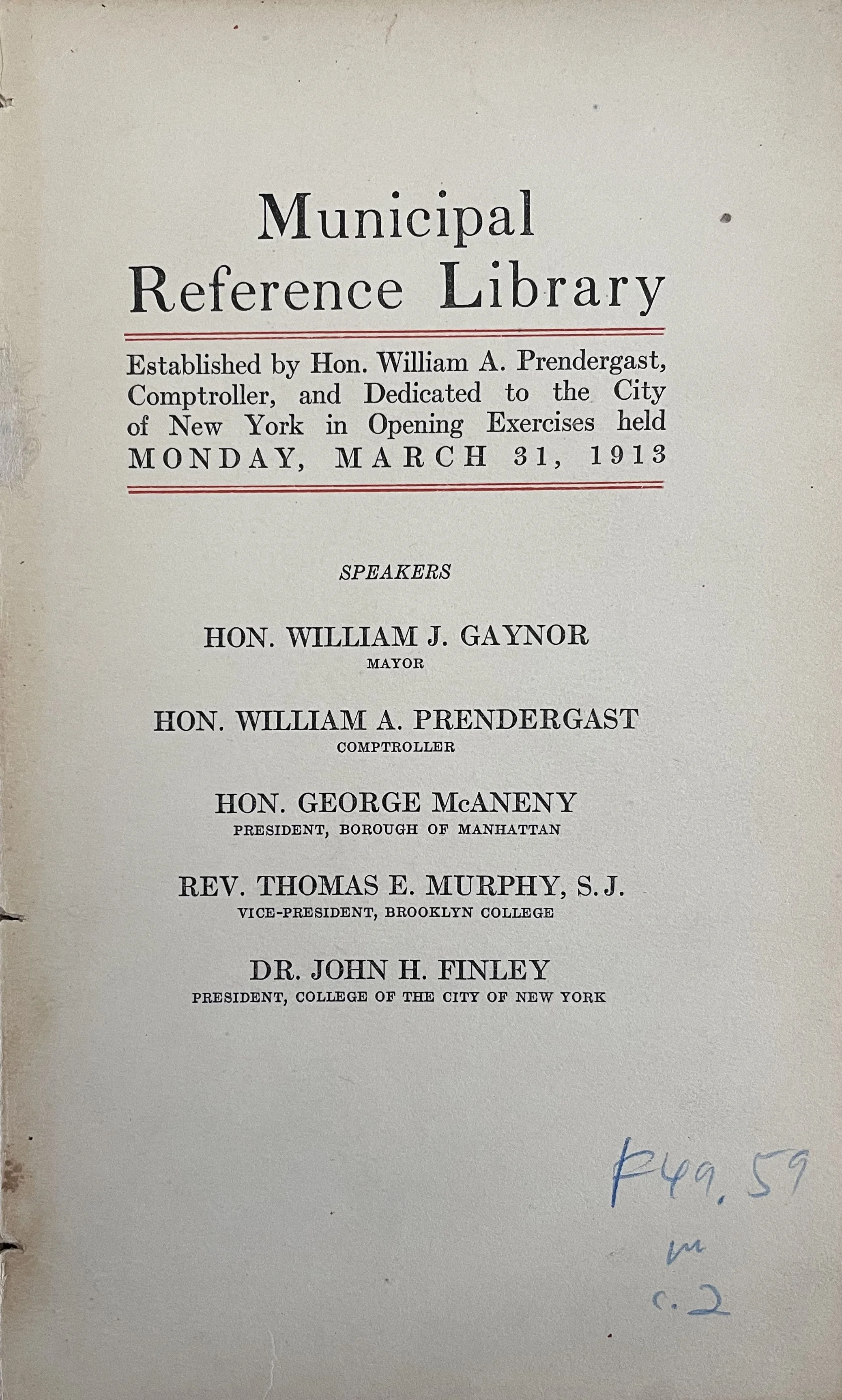

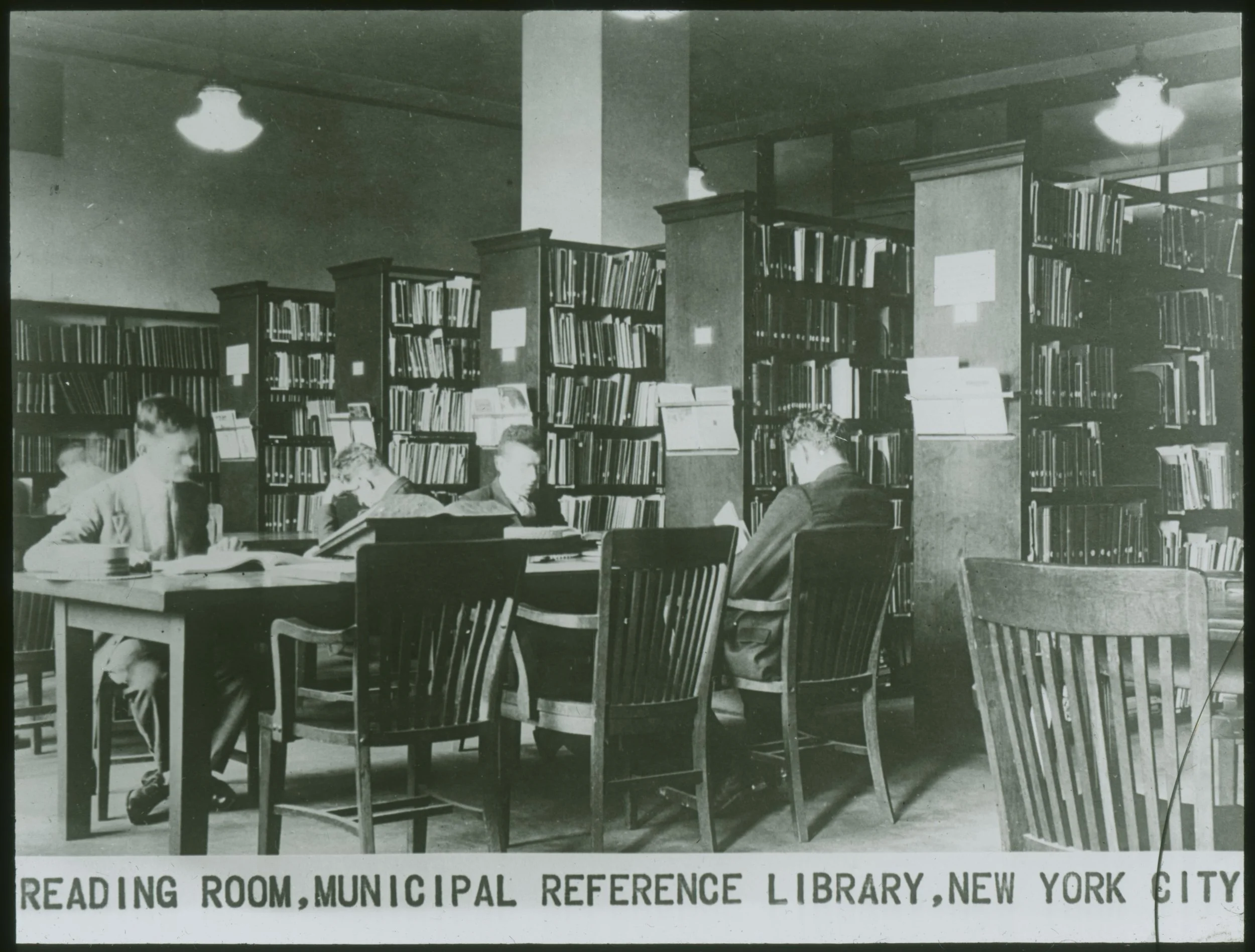

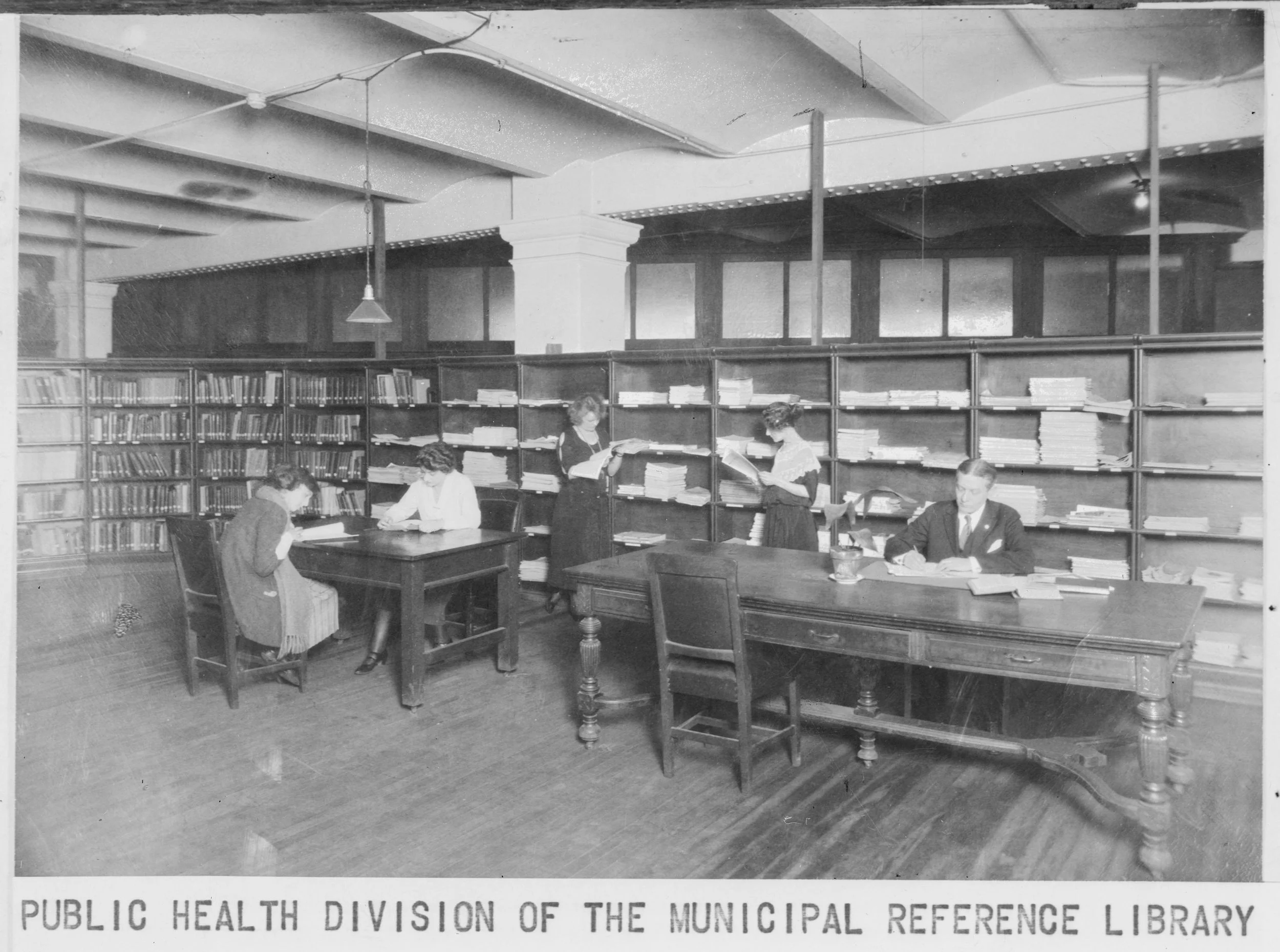

Researchers are also encouraged to search holdings of the Municipal Library. Based on the importance of public health-related information and publications, the Municipal Library maintained a separate branch at the Health Department, located at 125 Worth Street, from 1937through the 1980s. The Library has merged contents from the Health Department branch into the collection at 31 Chambers Street. Look for future For the Record articles that highlights Library holdings.