In March, 2025, For the Record introduced a new project “Processing and Digitizing Records of the New York City Commission on Human Rights (CCHR).” Supported by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) of the National Archives as part of their Documenting Democracy initiative, the project will enhance public access to records from the CCHR that have been transferred to the Municipal Archives. Key project activities include rehousing and processing 268 cubic feet of records and digitizing the earliest 53 cubic feet. Project archivists will publish an online finding aid, social media content and blog posts. They will also curate a digital exhibit that showcases both the collection and the project’s progress.

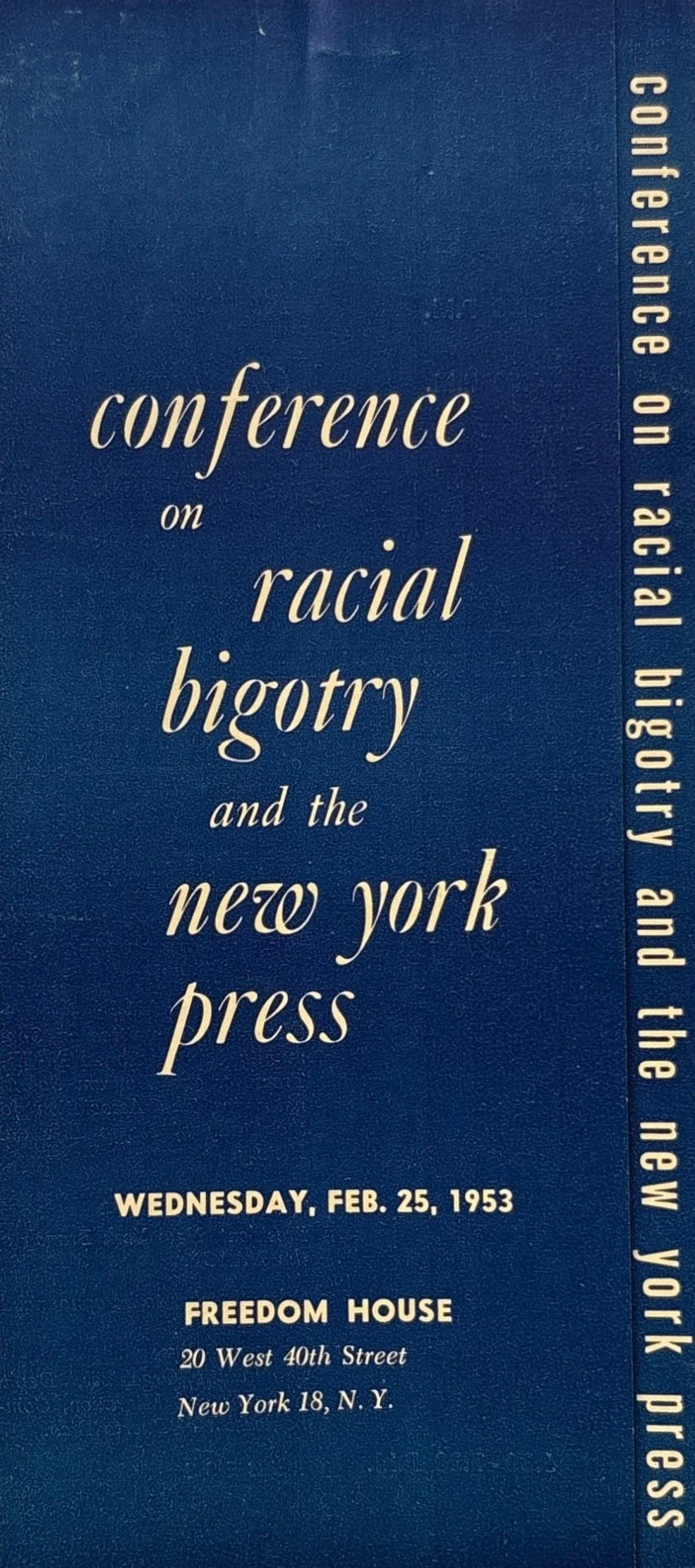

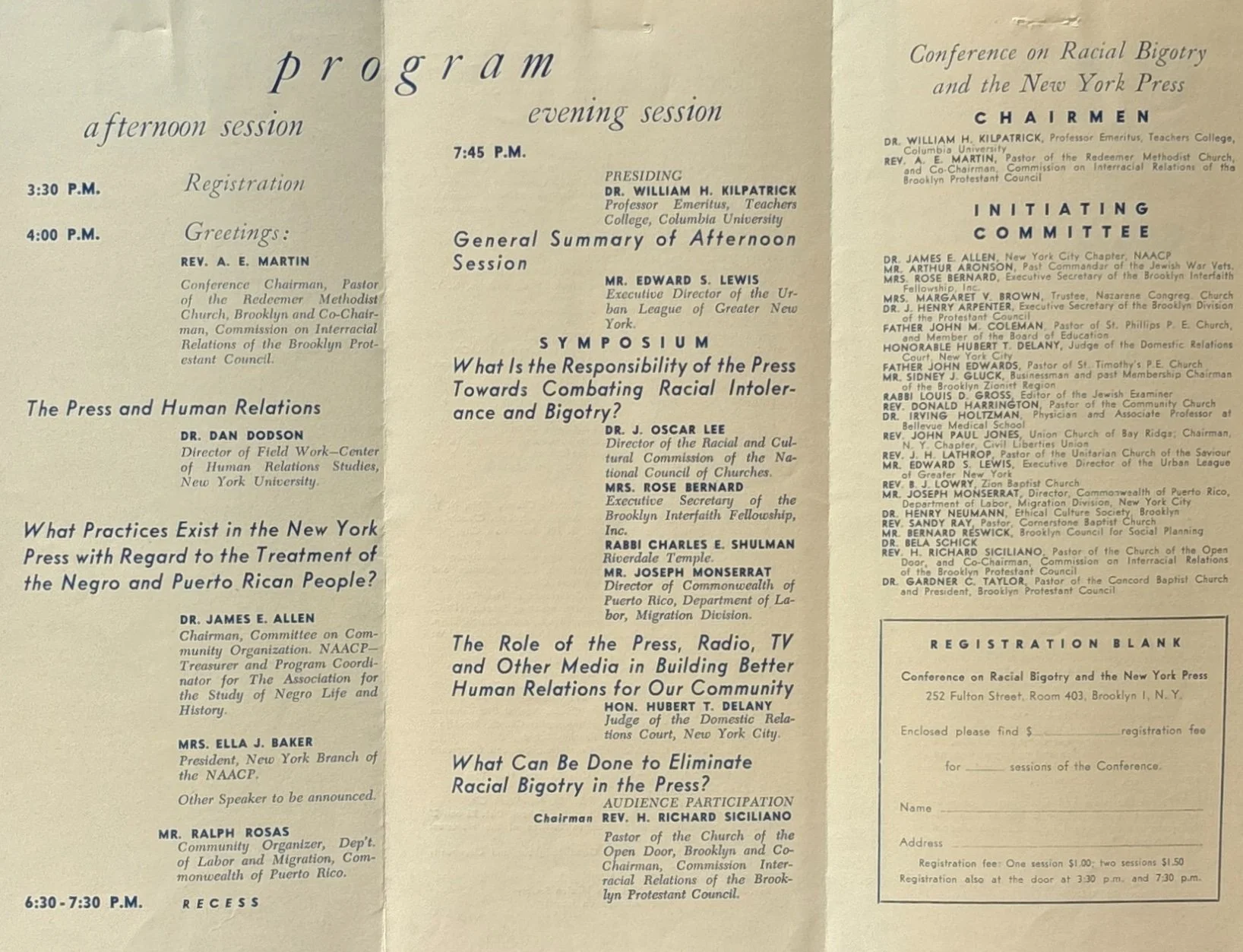

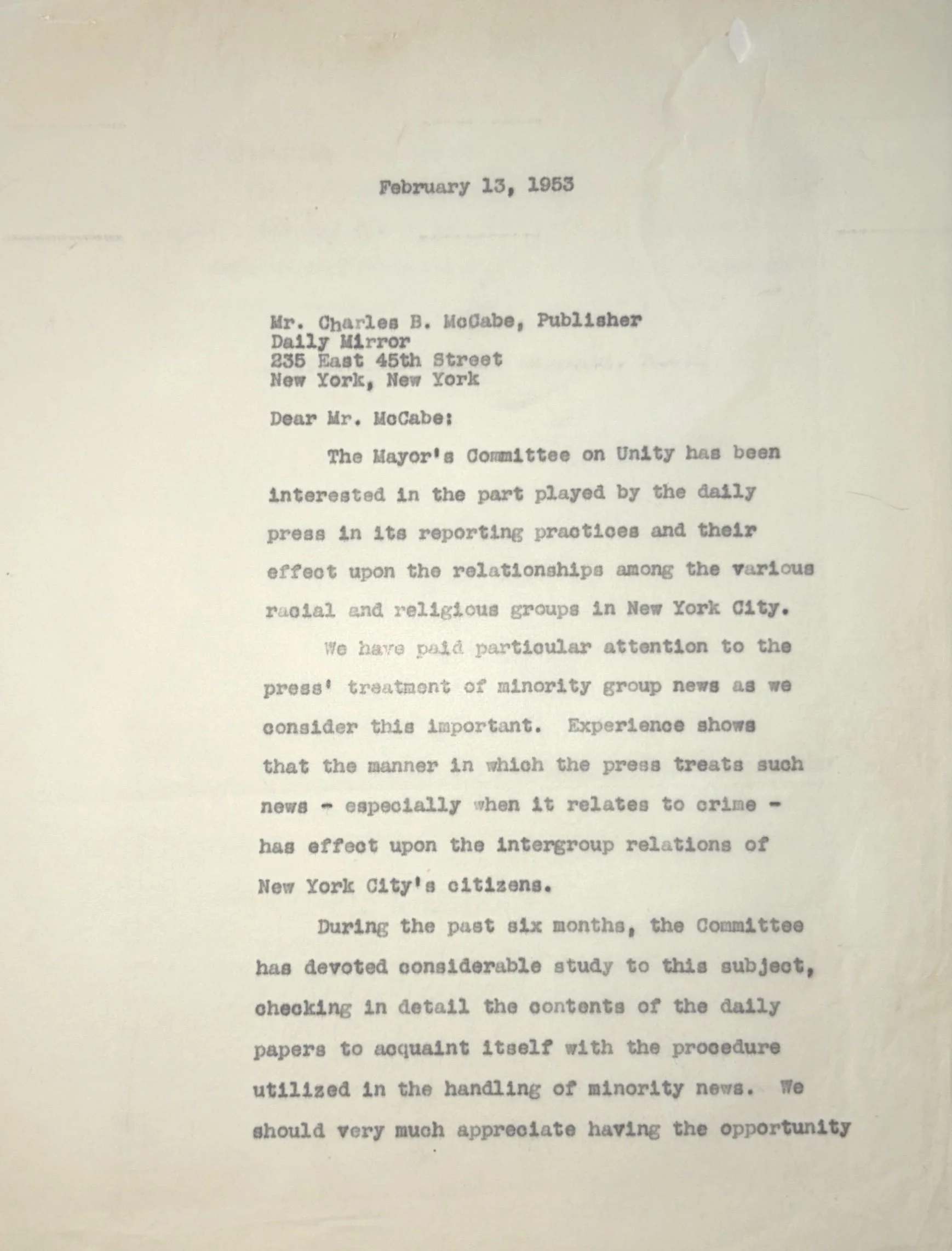

Pamphlet from conference on racial bigotry and the Press, 1953. REC0103, Box 27, Folder 6] CCHR Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

This post discusses how the Department of Records & Information Services (DORIS) developed a reparative description guide and how it was applied to the CCHR project. The post also describes an interesting parallel within the CCHR records.

Making of the DORIS Reparative and Inclusive Description Guide

In 2023, DORIS began developing the Guidelines for Reparative and Inclusive Description, a reference manual to assist Municipal Archives and Library staff in their reparative description practices. City Service staff Israt Abedin and Arafua Reed, City Service Fellows, coordinated the project. Other components included the publication of the agency's Harmful Content statement, several community engagement campaigns including the In Her Own Name research-a-thon and the Records of Slavery transcription project. All fit within the agency's diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility (DEIA) initiative. The manual uses a question/answer format to address questions that may emerge in day-to-day work, such as how to acknowledge uncomfortable or brutal imagery and language that is outdated. Creation of the guide drew from the researcher input, guides developed by various other repositories, and a theoretical understanding of the archivist’s role. For the Record published an update on the project in June 2024. The document was completed in the spring of 2025 and first utilized by archivists processing the City Commission on Human Rights collection.

What is Reparative Description?

Reparative description has existed within the library and archival fields for some time. Many cite Howard Zinn’s essay “Secrecy, Archives, and the Public Interest” as a starting point to understanding those efforts. Throughout, Zinn argues that the idea of a “neutral” archive is impossible, because the people creating and preserving the record carry their own biases. Archival integrity is maintained by acknowledging biases may exist and adjust practices accordingly. The core of this work lies in power: the power of the record in establishing what is a “historical truth” and the power of the archivist in deciding how that “truth” is told. It also hinges on access; by expanding the language for an archive, the documents within become easier for diverse populations to find and to use.

This often means acknowledging that the people who created the records simply did not see humanity in the subjects of certain records, or the creation of those records sought to erase the humanity of others. It also means recognizing the silence or absences that a lack of documentation causes. It’s important that the records archivists maintain are not altered, but rather supplemented with additional information that acknowledges the harmful language and/or bias within the initial statement. How does one implement that without causing more harm? This is an ongoing question that responsible archivists ask, as the answer is not fixed, but rather evolves with time.

Reparative Description in the City Commission on Human Rights Collection The City Commission on Human Rights collection proved to be a good selection for implementation of the reparative description guide due to the nature of the agency’s work and relationship to the communities they serve. An example of how archivists used the guide involved addressing pre-existing folder titles created by the Commission. During the processing phase, archivists determined that preservinge the original naming conventions provided historical context. As can be expected, language describing minority groups from the 1940’s-1970’s is outdated, making this older terminology a candidate for redescription. To balance historical accountability with contemporary access, original language was retained, and reparative description was added in brackets. Simply replacing outdated or harmful language entirely would erase evidence of past harm and introduce inconsistencies that ultimately hinder research and accountability.

Here are some real examples from the collection that used reparative description in the folder titles:

Meeting September 14, 1949: Department of Welfare Request Regarding Alleged Discrimination in Lodging Houses Against Negro [Black] Homeless [Unhoused] Men

5452-J-PH Employment-Physical Handicap [Physical Disability]

The first example comes from records in the collection created by a predecessor to the CCHR, the Mayor’s Committee on Unity (1943-1955). The second folder title comes from case files created by the CCHR between 1969 and 1976. This series captures complaints of discrimination that individuals had raised against employers, landlords, schools, and places of public accommodation (bars, restaurants, stores, etc.). Each file includes descriptions of incidents, notes from investigations, correspondence, evidence, and records of resolutions along with the reasoning behind them. Each case file has a code with a purely numeric order number and an alphabetic code which indicates what type of situation brought about the discrimination being reported (Employment, Housing, Public Accommodation, Education) and, in some cases, the type of discrimination, as in the case above which indicates that the complainant was filing for physical disability discrimination in employment.

Reparative Description and the Subcommittee on Press Treatment of Minority Groups

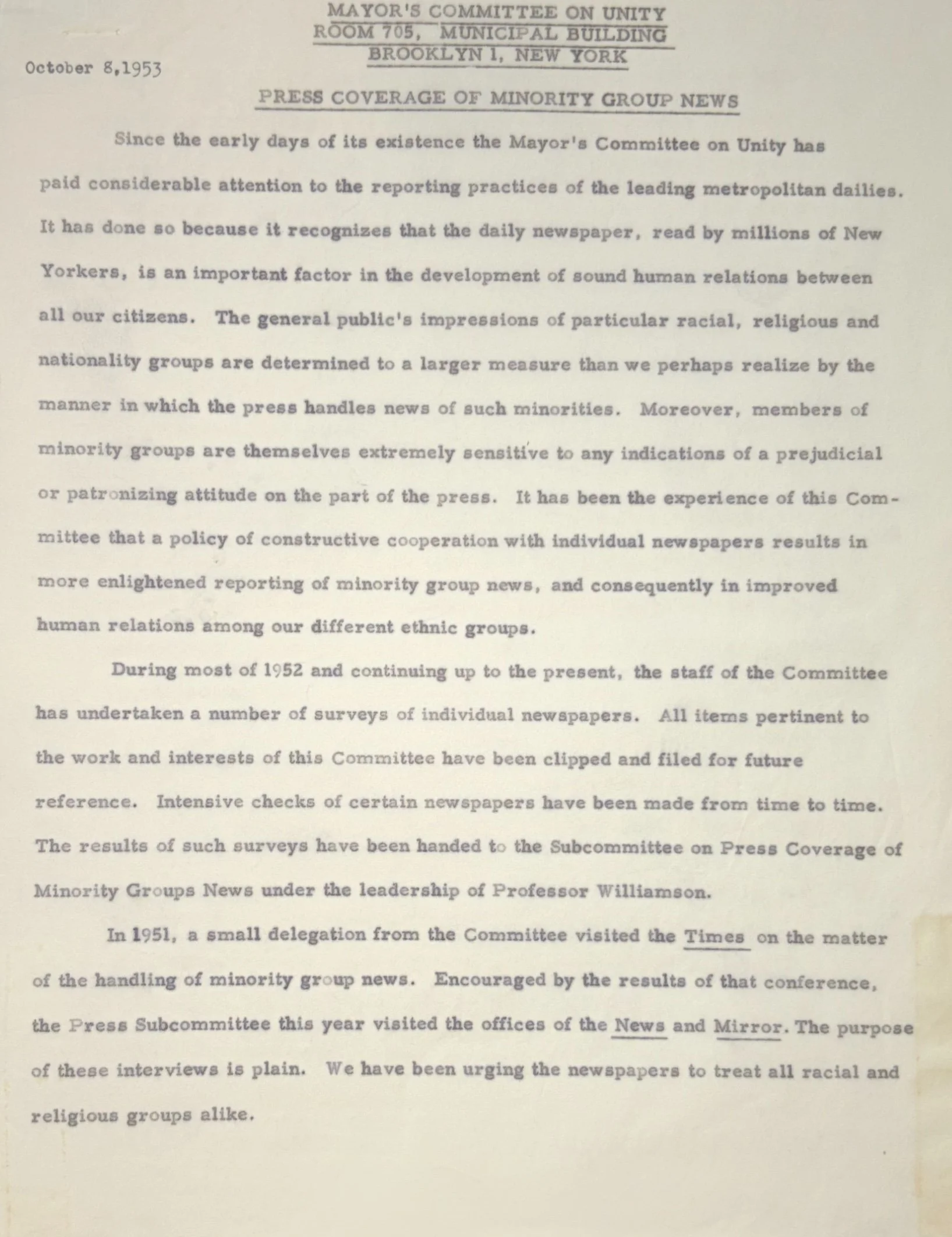

A particularly revealing parallel within the CCHR collection appears in the Commission’s earliest records. The Mayor’s Committee on Unity established a Subcommittee on Press Treatment of Minority Groups to engage directly with local newspapers to promote fair and non-discriminatory standards for news coverage.

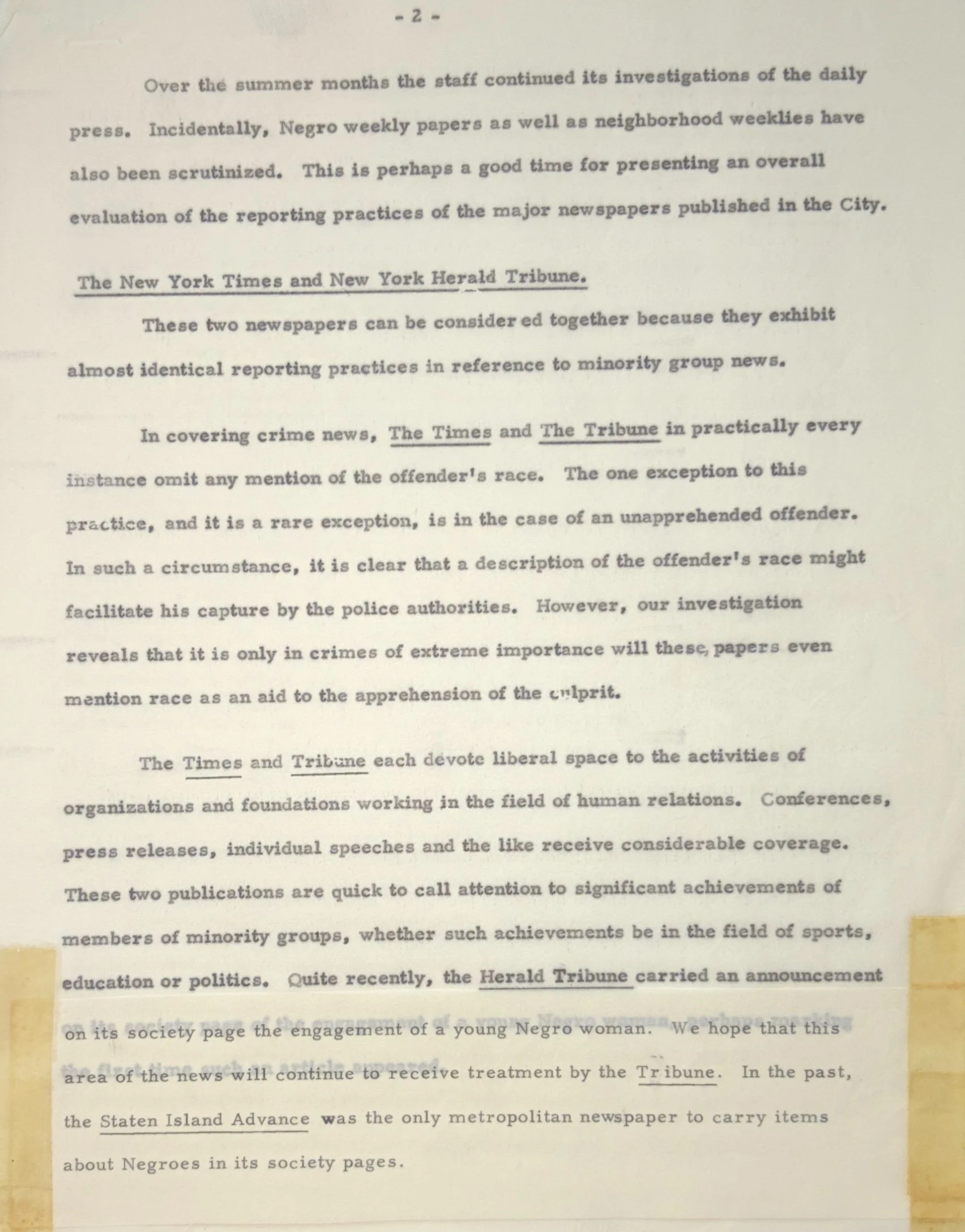

The Mayor’s Committee on Unity recognized the powerful role local newspapers played in shaping public perception of minority communities and potentially fueling social tension. In response, the Subcommittee spent years systematically reviewing reporting patterns and inflammatory language in the city’s major newspapers. Members compiled data to identify coverage that contributed, often unconsciously, to the escalation of racial and ethnic tensions within the city’s communities.

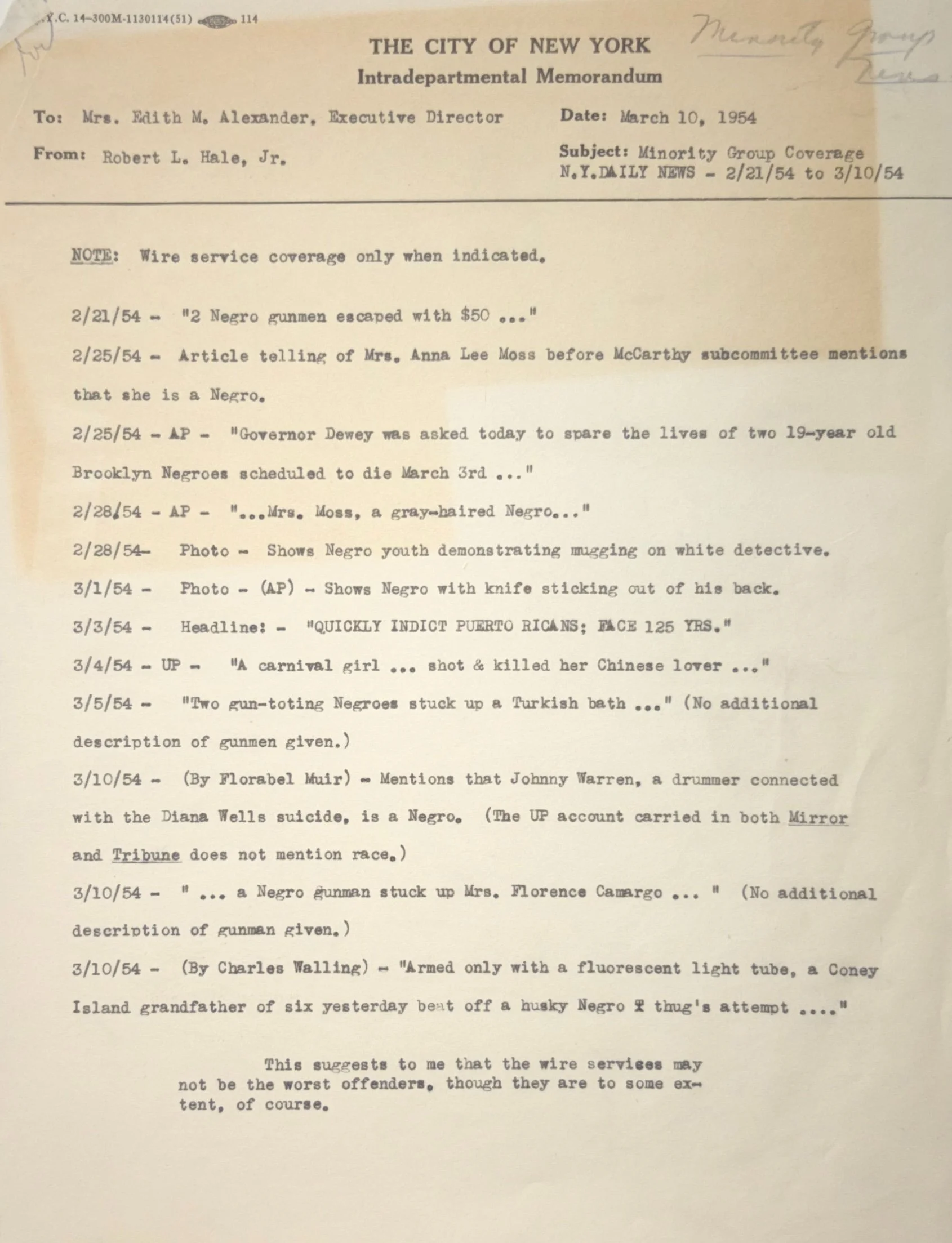

Data List, Box 27 Folder 6, CCHR Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Their reports detailed the language used and reporting patterns of local newspapers.

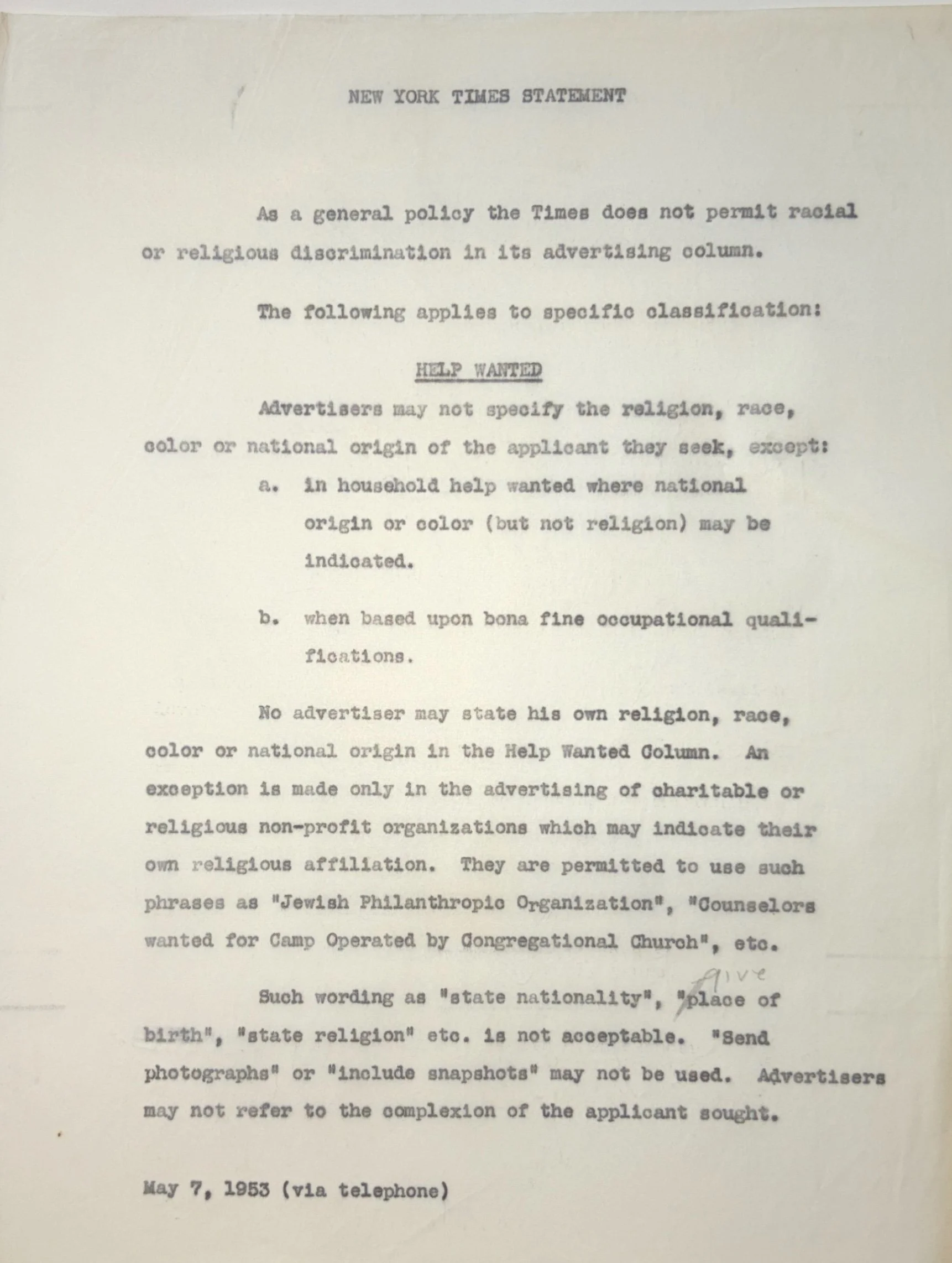

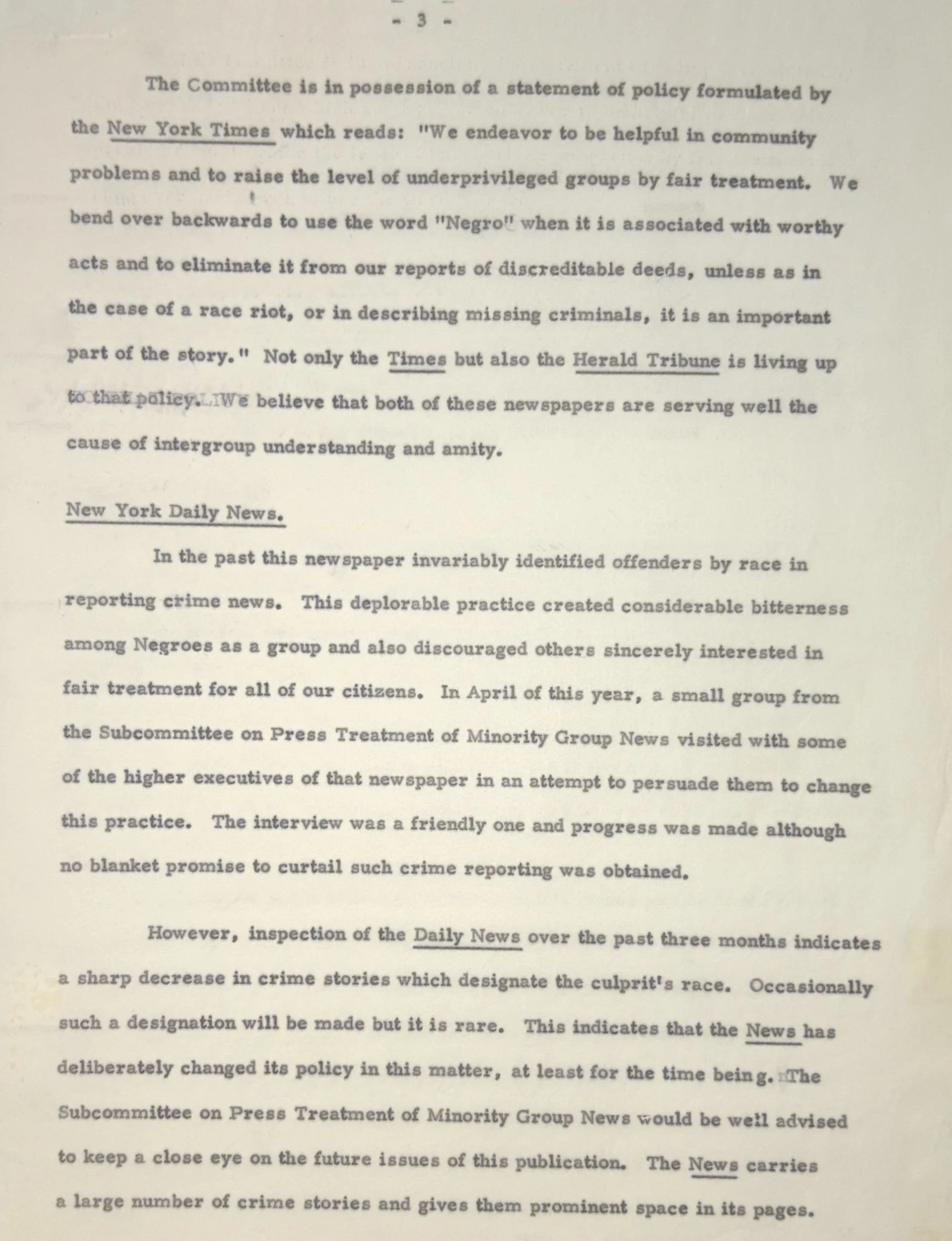

They engaged directly with editors of local newspapers whose reporting practices raised concerns, sharing findings and assisting in the development of protocols designed to address racial and religious bias in coverage.

New York Times protocol. REC0103, Box 27, Folder 6. CCHR Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

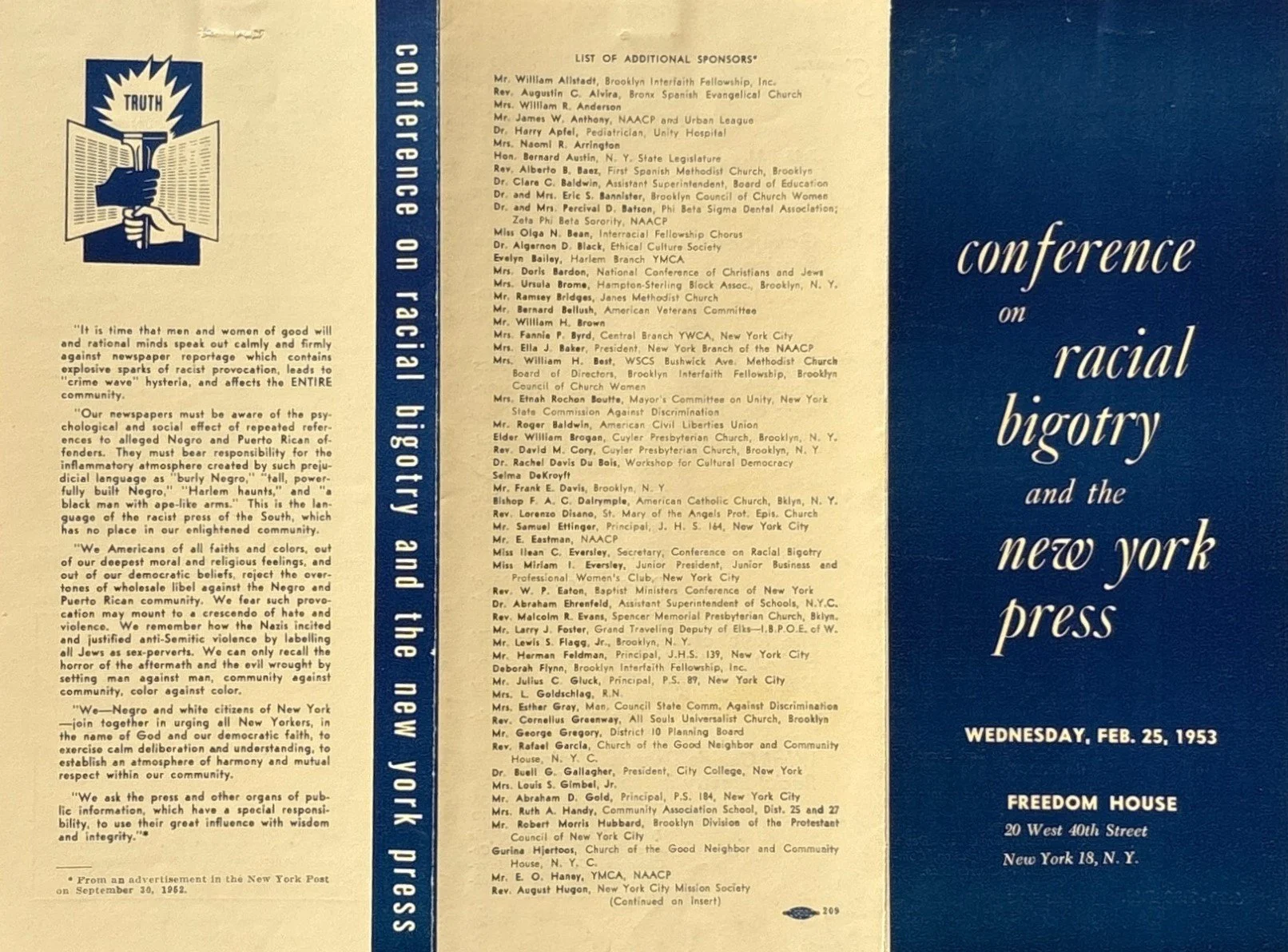

They also took part in conferences aimed at journalists, where they examined the broader implications of inflammatory language in news reports and its power to shape public perceptions of minority groups.

Pamphlet from conference on racial bigotry and the Press, 1953. REC0103, Box 27, Folder 6] CCHR Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Pamphlet from conference on racial bigotry and the Press, 1953. REC0103, Box 27, Folder 6] CCHR Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

There is a clear parallel between the work of the Subcommittee on Press Treatment of Minority Groups and the contemporary archival work taking place in the CCHR project through reparative description. Both efforts engage institutions that are often treated as neutral or authoritative sources of truth: the news media and the archive. In each case, information is not passively recorded but actively shaped through processes of selection, description, and framing by individuals working within institutional systems. The language used to describe events, people, and histories, whether in newspaper headlines or archival folder titles, plays a significant role in how those subjects are located, understood and remembered. When prior descriptive practices go unquestioned, institutional authority can mask the biases embedded within, allowing harmful narratives to persist as accepted truth. By examining and intervening in these frameworks, both the Subcommittee and contemporary archivists challenge assumptions of neutrality and make visible how descriptions can either reproduce harm or allow accountability and repair.

Conclusion

The City Commission on Human Rights collection offers a strong example of how institutional language shapes public understanding. The Subcommittee on Press Treatment of Minority Groups shows an awareness of the power of description and a willingness to intervene when those descriptions caused harm. When applying contemporary archival practices such as reparative description, the collection shows how questions of representation, accountability, and institutional responsibility have been negotiated over time.

Today’s post was written in collaborative effort between Arafua Reed, who contributed to the writing of the Reparative Description Guide and Neen Lamontagne, the project archivist managing the City Commission on Human Rights grant project.