For 73 years, WNYC was owned and operated by the City of New York. Detailing its African-American-focused programing over this period is no small task—indeed, it could easily serve as a master’s thesis in broadcast history. Within the limits of this essay, however, I have highlighted some of the most significant early moments and broadcasts that merit reflection during Black History Month.

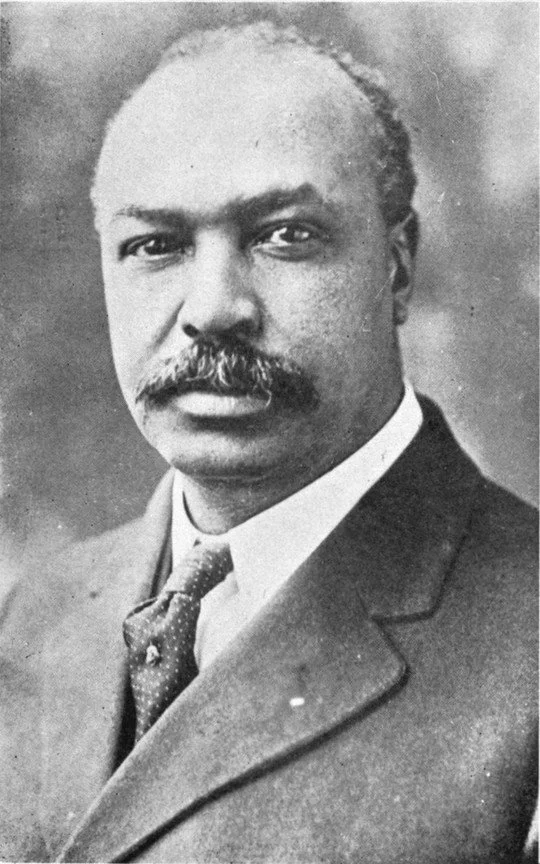

Reverend Dr. Henry Hugh Proctor. Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

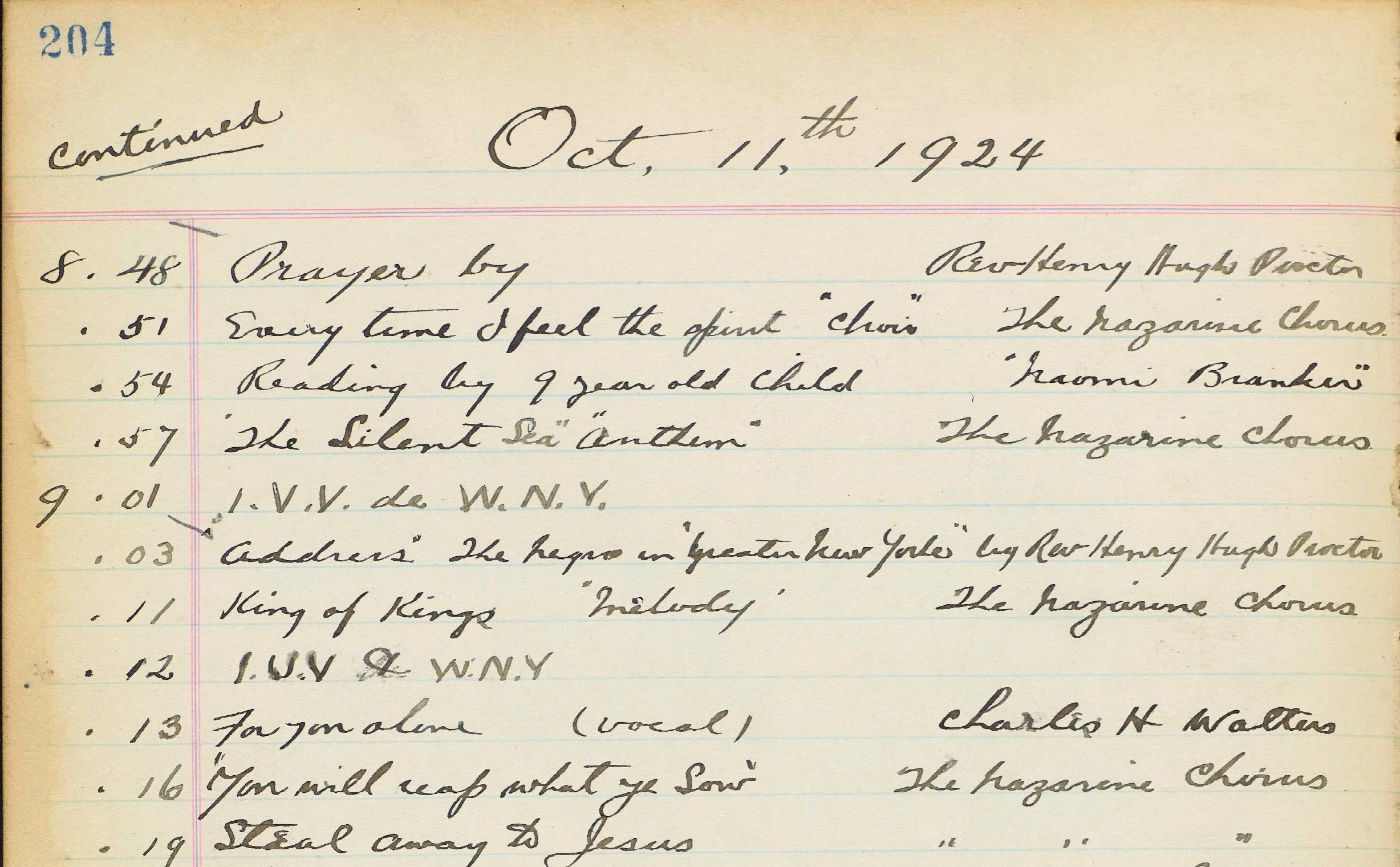

Among the earliest African American speakers on WNYC—if not the first—was the Reverend Dr. Henry Hugh Proctor, an early civil-rights leader who addressed listeners on the evening of October 11, 1924. He opened the broadcast with a prayer, followed by the Nazarene Chorus, based at his Brooklyn church, the Nazarene Congregational Church. Proctor is recognized as a key figure in the Social-Gospel movement, a significant precursor to the modern civil-rights movement.

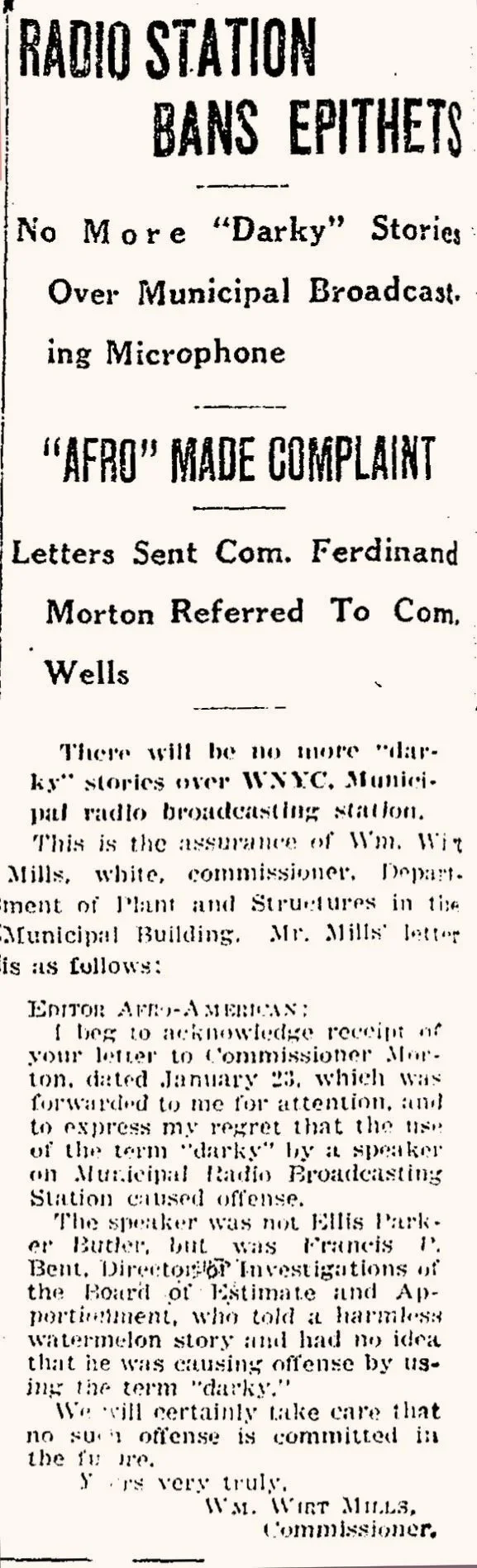

The municipal station was only eight months old in March 1925—and radio itself was still very much a toddler—when WNYC banned the use of racial epithets on the air. The action came at a moment of peak Ku Klux Klan membership nationwide and three years before NBC would launch the enormously popular, and racially charged, Amos ’n’ Andy. The ban followed a broadcast in which a city official told “a harmless watermelon story,” unaware that he had caused offense by using a slur related to skin color.” Department of Plant and Structures Commissioner William Wirt Mills, whose agency oversaw the station, issued an apology and ordered corrective action in response to a complaint from The Baltimore Afro-American newspaper.

Excerpt from WNYC Engineering Log for October 11, 1924. WNYC Archive Collections.

The Baltimore Afro-American, March 7, 1925, pg.6.

Seen in this light, it is notable that by 1946—likely earlier—the station’s operations manual extended its prohibition on racial and ethnic epithets to Jews, Irish Americans, and other maligned groups. The guide also instructed staff that “there is no need, for example, in crime news to refer repeatedly to a man's color unless there is a specific news reason, such as a police description of a missing person.” It further cautioned against repeating derogatory remarks about any individual, even when accurately attributed, unless the quotation itself had specific news value, such as forming the basis of a lawsuit.

Black participation on WNYC and other broadcast outlets during the 1920s remained limited, largely confined to occasional gospel performances and dance band appearances. That changed in 1929, when both the New York Urban League and the NAACP secured regular weekly time slots—among the earliest sustained programming by and for African Americans in the nation. These broadcasts featured prominent voices including scholar and activist W.E.B. Du Bois, labor leader A. Philip Randolph, writer and civil rights advocate James Weldon Johnson, and actress Rose McClendon.

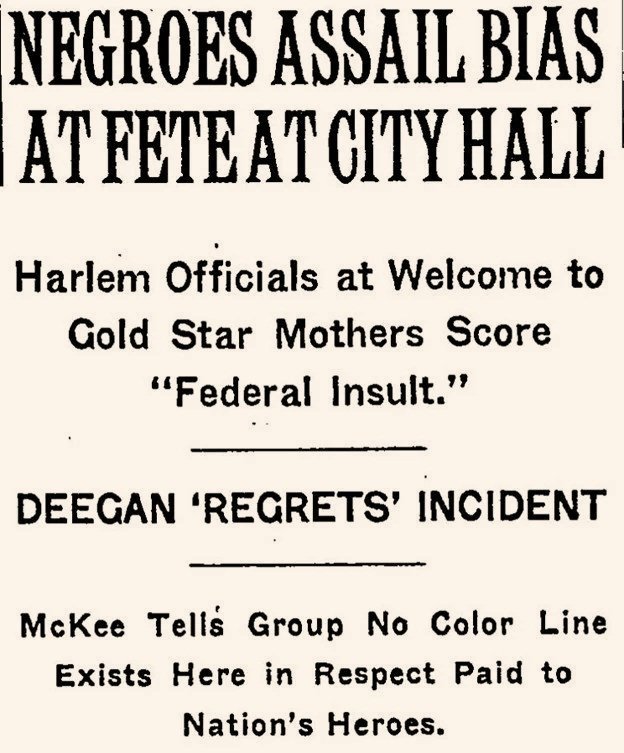

Between 1930 and 1933, the U.S. government sponsored trips to Europe for surviving mothers of deceased World War I soldiers and for widows who had not remarried, allowing them to visit the American cemeteries where their loved ones were buried. The program was initially praised in Black newspapers, which encouraged all eligible women to participate. That support shifted, however, when the War Department announced that the pilgrimages would be segregated.

Mrs. Willie Rush, whose son died in France, spoke over WNYC on behalf of Gold Star mothers during a City Hall protest broadcast on July 11, 1930. An Atlanta native, she condemned the segregation of the Black and white delegations. She and other protesters were joined in the Aldermanic Chamber by Acting Mayor Joseph V. McKee and city officials.

The NAACP attempted to persuade the federal government to integrate the excursions but was unsuccessful. The organization subsequently called for a boycott, prompting roughly two dozen mothers and widows to cancel their trips. Ultimately, however, 279 African-American women chose to make the journey.

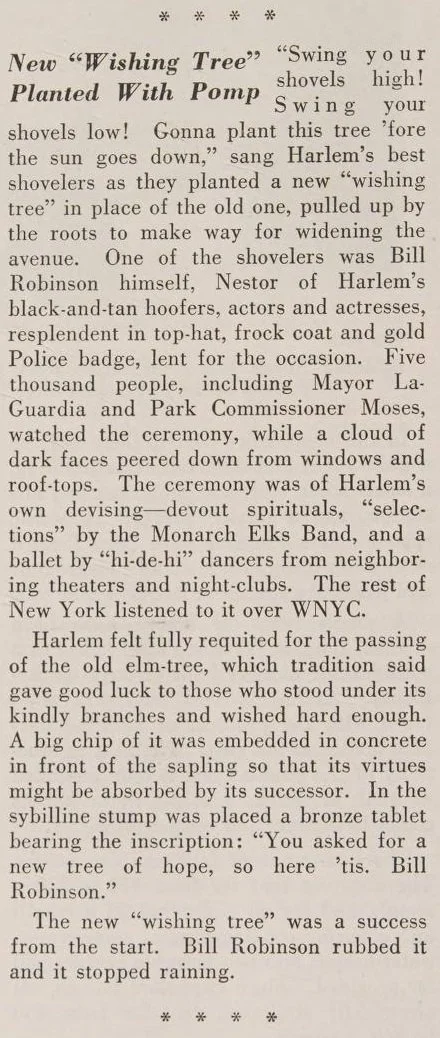

Planting ceremony of the Tree of Hope, Seventh Avenue and 131 Street, where out-of-work black entertainers traded gossip and tips on jobs, November 1934. Mayor LaGuardia collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

November 17, 1934 edition of Literary Digest courtesy of the Internet Archive.

An unusual event celebrating legend, myth, and collective hope brought WNYC microphones to Harlem on November 4, 1934. The occasion was the replanting and dedication of the community’s “Wishing Tree” at 131st Street and Seventh Avenue, with Bill “Bojangles” Robinson presiding before public officials and a crowd of thousands. Also known as the “Tree of Hope,” the elm was believed to possess magical powers, according to reports in The Literary Digest.

Planting ceremony of the Tree of Hope, Seventh Avenue and 131 Street, where out-of-work black entertainers traded gossip and tips on jobs, November 1934. Mayor LaGuardia collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Shortly thereafter, newly hired assistant program director Seymour Siegel moved quickly to bring government-subsidized musicians into the municipal studios through the Federal Music Project. Although the program remained segregated and Black musicians were paid less than their white counterparts, African-American performers were nonetheless employed under the WPA. The ensembles were broadcast nationally via 16-inch transcription discs mailed from Washington, D.C.—a pre-satellite distribution system. These groups included the Juanita Hall Choir, the Negro Melody Singers, the Negro Art Singers, the Los Angeles Colored Chorus, and the Los Angeles Negro Choir.

The WNYC Archives compiled this mixtape of 26 performances selected from the Municipal Archives WNYC Collection of WPA music transcriptions.

Singer and actress Juanita Hall, with back turned, conducting the Negro Melody Singers, circa late 1930s. Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations / New York Public Library.

Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia’s second term in 1938 marked another turning point with the appointment of Morris Novik as station director and head of the Municipal Broadcasting System, a communications agency reporting directly to the Mayor rather than the Department of Plant and Structures. This reorganization ushered in a new era of inclusiveness at WNYC, beginning with an on-air discussion and debate over the federal Anti-Lynching Bill featuring NAACP executive secretary Walter White. The period also included a notable studio performance by actor Alvin Childress, who portrayed an enslaved person in a dramatic sketch titled Two Faces.

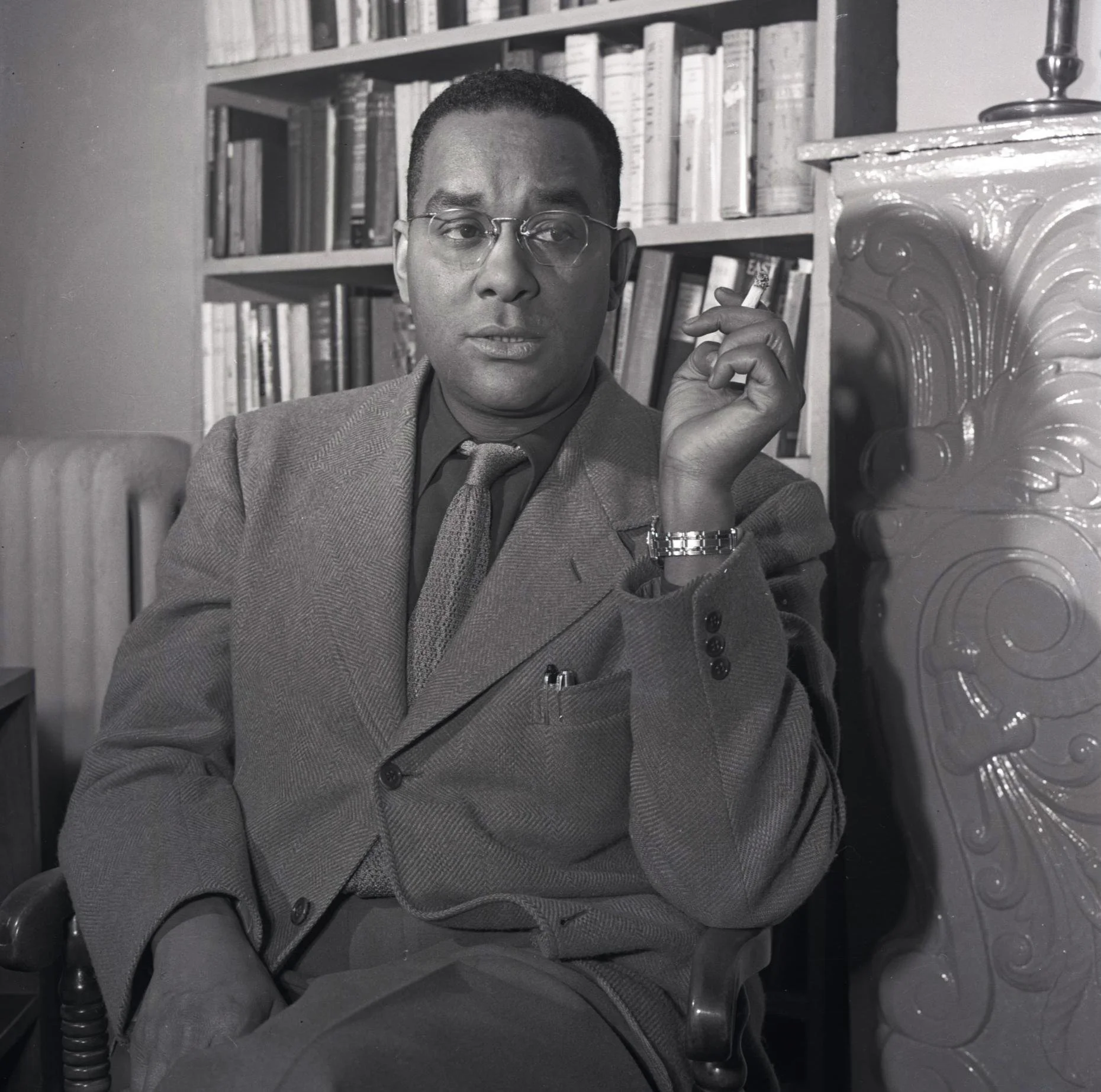

Portrait of author Richard Wright (PM Photo/A. Lanset Collection).

In April of that year, author Richard Wright appeared on a Federal Writers’ Project roundtable broadcast and addressed the persistence of racial stereotyping and reflected on his work for The WPA Guide to New York City. “The most amazing thing about these stories, to my way of thinking, is that they were never done before… the average American's conception of Negro culture and life as it exists in New York is probably derived from not very accurate novels, or Hollywood representations of the urban Negro as either shabby and comical or exceedingly prosperous as the conductor of a popular swing orchestra.”

The following month, the National Urban League launched Negro News & Views, a new weekly program intended, in its words, “to awaken the general public to the realization of the importance of the Negro’s cultural contribution to American life.” Two weeks after the funeral of James Weldon Johnson in June, WNYC broadcast an on-air remembrance of the author of Lift Every Voice and Sing, often referred to as the Black national anthem. Listeners heard tributes from Mayor La Guardia and leaders of the NAACP, underscoring the station’s growing role as a civic platform for Black cultural and political life.

In 1939, African-American actor Gordon Heath came to WNYC through the WPA’s National Youth Administration via its NYA Varieties radio program. He produced a biographical series titled Music and Youth, which he later recalled in his memoirs as a stream of “15-minute potted sketches from the lives of great musicians of the past.” One such vignette featured Beethoven in conversation with his landlord, declaring, “Ah, Herr Sturch—the wages of sin, they have not been paid.”

Part Two of the blog will continue documenting WNYC’s role as a leading producer of programs focusing on Black civic and cultural leadership in the 1940s.