The 1940s

The wartime decade placed WNYC firmly in the vanguard of American broadcasting where Black producers and Black-centered programming were concerned. This leadership emerged early in the decade with calypso music on Henrietta Yurchenco’s Adventures in Music. A notable example is the July 28 broadcast featuring Cecil Anderson—better known as The Duke of Iron—who paid tribute to the municipal station in song with “The Ballad of WNYC.”

Station WNYC. Yes, WNYC, it is owned by the people of N.Y.C.

My friends, I’m known as the Duke of Iron,

And I sing to people throughout the land.

I came from Trinidad, maybe you have heard

Of the glorious land of the humming bird.

I highly appreciate your loyalty

And the grand privilege that’s offered me

By the nice people of New York City

And the station WNYC…

The Duke of Iron (Cecil Anderson) publicity photo, Wikimedia Commons.

In the song, Anderson also praised Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, crediting him as the station’s “godfather” and acknowledging his tireless efforts to ensure WNYC’s survival during its early years—although it’s worth noting that La Guardia originally ran for Mayor on a platform calling for the abolition of the station given its cost to the taxpayer.

Producer Yurchenco also brought Huddie Ledbetter—Lead Belly, the king of the twelve-string guitar—to WNYC’s air in 1940. This appearance marked the first of four regular series he would host during the decade, along with frequent guest spots on other programs, including the annual American Music Festival. In a 2001 interview with WNYC, Yurchenco recalled his professionalism, punctuality, and meticulous dress, as well as the collaborative way they shaped his broadcasts. She emphasized that Lead Belly’s commentary drew directly from his own life and described it as “colorful and magnificent,” noting that he remains one of the great blues singers of all time. Here is Lead Belly from his program, Folksongs of America, on February 27, 1941.

Among the other programs on which Lead Belly appeared was Ralph Berton’s Metropolitan Review, radio’s first serious jazz music program, and its companion series, Jazz Institute on the Air. Together, these broadcasts introduced New York audiences to a wide range of African American jazz, blues, boogie-woogie and swing artists in the early 1940s. In November 1941, Berton devoted a full week of programming to Louis Armstrong—whom he dubbed “the Beethoven of hot jazz”—in celebration of Armstrong’s twenty-fifth year in show business. Berton also hosted a segment of WNYC’s American Music Festival in February 1941 featuring Lead Belly, Albert Ammons, Sam Price, Meade Lux Lewis, and the Golden Gate Singers.

(Audio from the Municipal Archives WNYC Collection)

Paul Robeson by Gordon Parks for the OWI, June 1942/Library of Congress.

Paul Robeson’s powerful baritone graced WNYC’s airwaves on at least two occasions during the 1940s. The first occurred on June 24, 1940, when he performed “Ballad for Americans” at Lewisohn Stadium with the Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra conducted by Artur Rodziński. Written by Earl Robinson and John Latouche, the cantata was conducted by Mark Warnow and featured a chorus of fifty voices drawn from the Schola Cantorum and the Wen Talbert Negro Choir, with African American contralto Louise Burge joining the ensemble. The concert also included the premiere of William Grant Still’s And They Lynched Him on a Tree, based on a poem by Katherine Garrison Chapin. Robeson’s second live WNYC broadcast was a Central Park bandshell concert of contemporary Russian music on September 1, 1942, conducted by noted African-American conductor Dean Dixon.

From May through July 1941, WNYC aired the pioneering thirteen-week dramatic series Native Sons, which portrayed the lives of significant historical Black figures. The biographical sketches were groundbreaking not only in content but in authorship: they were written by African Americans Kirk Lord and Frank D. Griffin at a time when few Black writers worked in radio beyond menial roles. Writing for the Baltimore Afro-American in August 1941, Griffin charged that commercial radio would not hire Black writers, arguing that as radio became a big business, Jim Crow practices had become entrenched in both studios and control rooms. Two years later, The New York Age noted Griffin’s hiring by the Congress of Industrial Organizations to write NBC’s Labor for Victory series, observing that he was “the only Negro at present writing for a network program.”

Headline from the August 1, 1941 radio listings in the Daily Worker.

Native Sons also broke new ground by presenting profiles of insurgent figures such as Nat Turner and Denmark Vesey—subjects rarely, if ever, discussed on the air. Alongside these were portraits of figures including Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, Crispus Attucks, George Washington Carver, Benjamin Banneker, Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield, Paul Robeson, Marian Anderson, Roland Hayes, Dorothy Maynor, Ira Aldridge, Robert Smalls, Toussaint L’Ouverture, and the Moroccan explorer Estevanico. The series featured an all-Black cast that included Canada Lee, Jessie Zackerey, P. J. Sidney, Jimmy Wright, Rose Poindexter, and Eric Boroughs, with musical segments provided by the Juanita Hall Choir. Author Richard Wright delivered commentary following the final broadcast.

Clifford Burdette/NAACP Collection – Library of Congress.

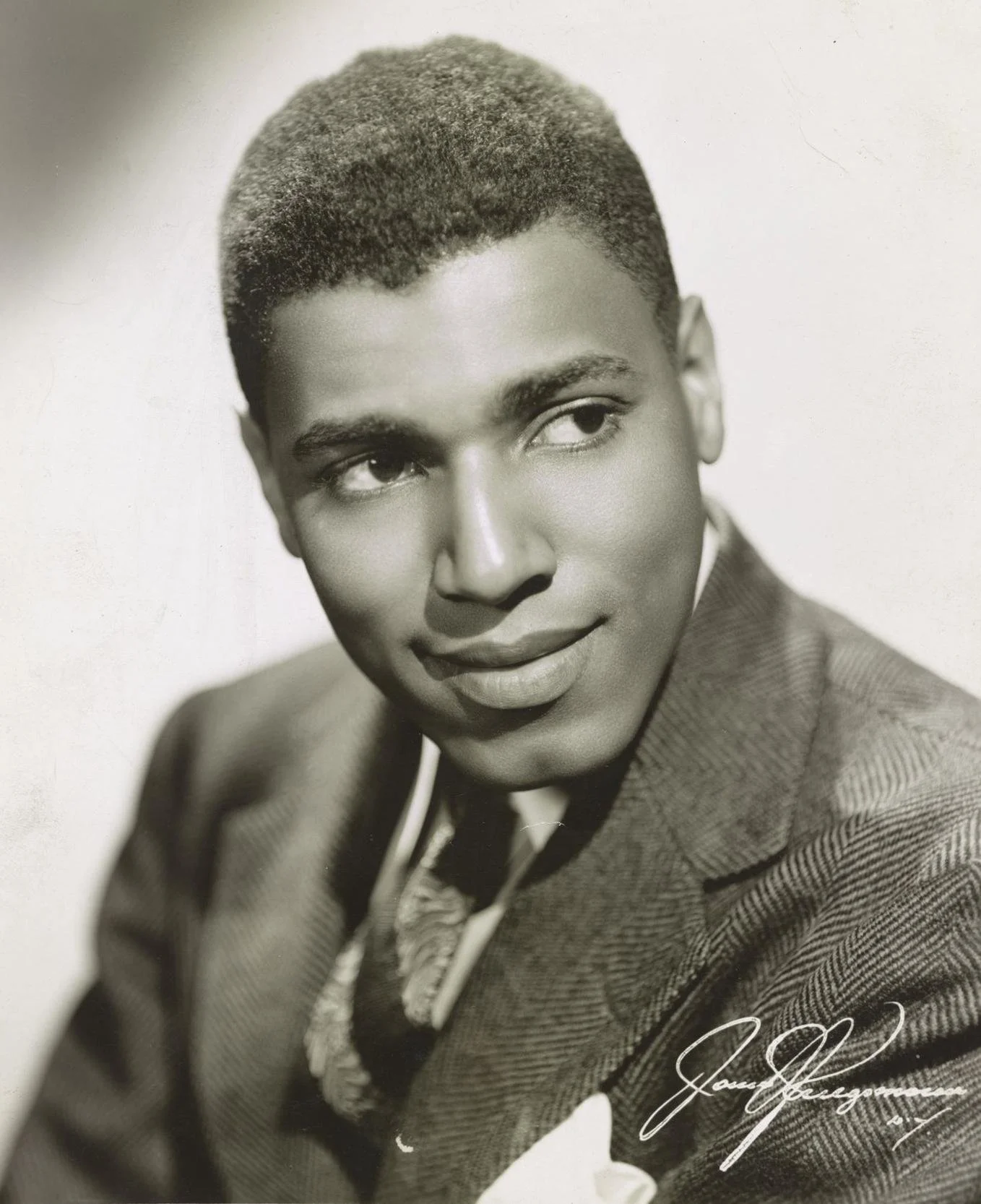

May 1941 also marked the debut of Those Who Have Made Good, an interview program sponsored by the NAACP and designed to spotlight “the most outstanding race figures in contemporary life, from all fields of endeavor.” Hosted and produced weekly by Clifford Burdette for more than a year, the program fulfilled that mission, beginning with actor Canada Lee and continuing with guests such as Paul Robeson, W.C. Handy, Josh White, Noble Sissle, Mercedes Gilbert, Dean Dixon, Count Basie, the Reverend Adam Clayton Powell, Hazel Scott, Max Yergan, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, and many others. The sole surviving recording of the series features Harlem poet Countee Cullen.

(Audio courtesy of the Amistad Research Center, Tulane University)

Duke Ellington’s first Carnegie Hall concert on January 23, 1943 featured his expansive jazz composition Black, Brown and Beige, a work he described as “a parallel to the history of the Negro in America.” Recorded on location, the performance was broadcast over WNYC nine days later. Unfortunately, critics initially received the work poorly, and Ellington never revisited it in full. Half a century later, however, Scott DeVeaux of the University of Virginia, described it as “an intriguing piece of music, well worth reexamining” and “a celebration of Black artistic achievement” that “confronted both the cultural snobbery that excluded jazz musicians from the musical establishment and the pervasive racism that excluded African Americans from their share of citizenship.”

Judge Jane Bolin, first black female to occupy a court bench/U.S. Office of War Information Photo/Wikimedia Commons.

On March 18, 1943, Justice Jane M. Bolin—the first African-American judge in New York and the first Black woman to graduate from Yale Law School—came to the municipal radio studio to deliver the address Womenpower is Vital to Victory. Bolin was speaking as part of the Eleventh Vocational Opportunity Campaign of the National Urban League. She called for employment of African-American women and condemned discrimination as antithetical to the nation’s democratic war aims.

WNYC revisited the African-American docudrama with the Great Americans series May 19 through June 23, 1943. Sponsored by the City’s Juvenile Welfare Council, the program included profiles of inventor George Washington Carver, champion fighter Joe Louis, contralto Marian Anderson, sculptor Richmond Barthe, police officer Samuel Battle, activist James Weldon Johnson, and heard here, ship captain Hugh Mulzac.

(Audio from the Municipal Archives WNYC Collection)

Compared to Native Sons, the series was more conventional and corny in tone. Variety commented that it “ducked the fundamental racial issues” and was “slanted for juves and strictly inspirational,” with episodes often concluding with exhortations about self-improvement.

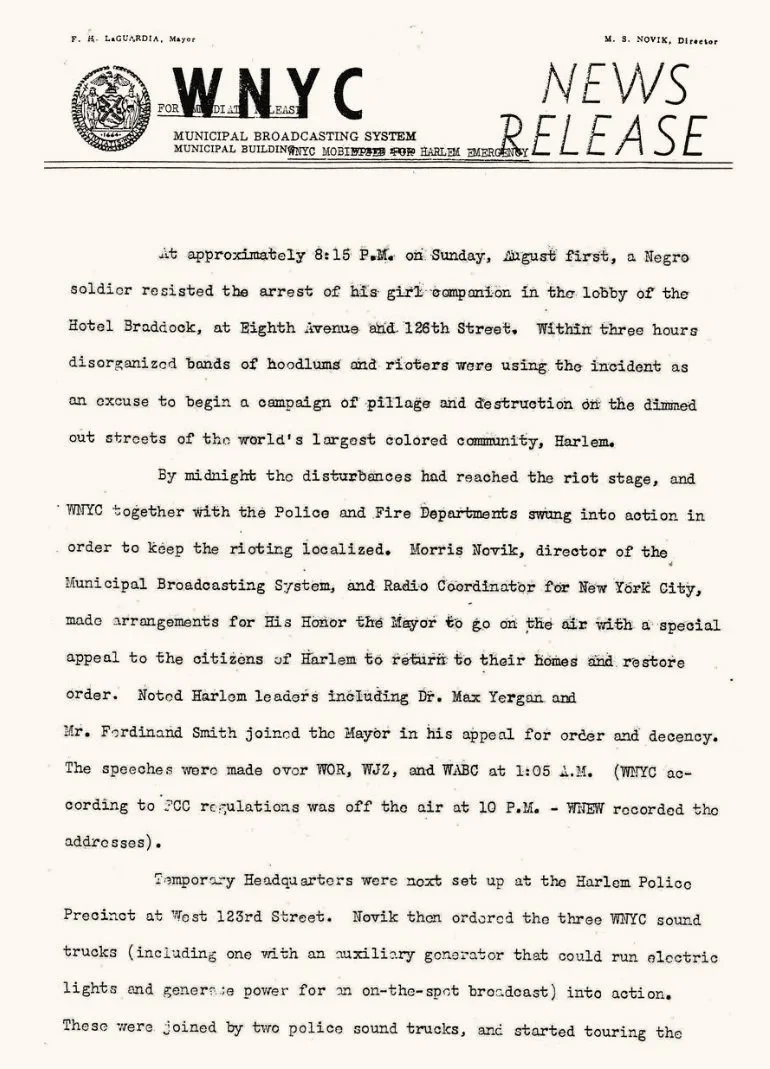

The year 1943 was marked by unrest tied to racial and ethnic tensions across the United States. Violent clashes erupted in Mobile, Alabama, Detroit, Los Angeles, and Beaumont, Texas, undermining morale on the home front as the nation fought a global war. Mayor La Guardia—also the national head of the Office of Civilian Defense—was deeply concerned that similar disturbances might erupt in New York, particularly given the reliance on minority soldiers in a segregated military.

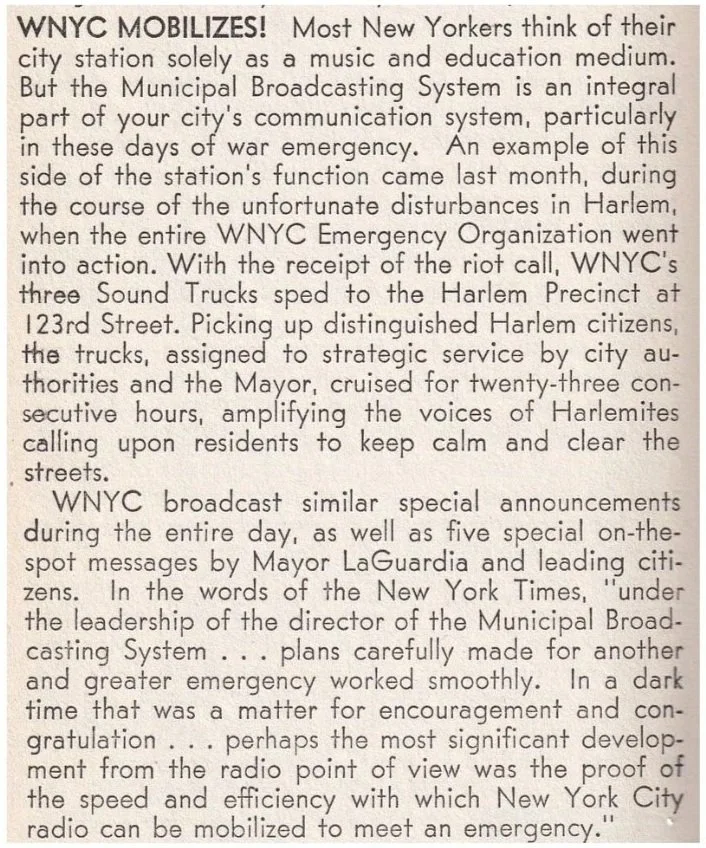

Seeking to defuse rising tensions, La Guardia pressed for a radio series titled Unity at Home – Victory Abroad and wrote poet, activist, and playwright Langston Hughes for assistance. Slated to air on WNYC and seven other New York stations in August and September, the series featured figures such as contralto Marian Anderson, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, and former governor Al Smith. Tragically, the effort came too late to prevent the Harlem riot of August 1, although WNYC played a critical role in calming the situation through its broadcasts and sound trucks.

(Audio from the Municipal Archives WNYC Collection)

Page one of a four-page WNYC press release on the 1943 disturbances in Harlem. NYC Municipal Library vertical files.

Excerpt from Behind the Mike, September/October 1943 Masterwork Bulletin/WNYC Archive Collections.

According to Hughes biographer Arnold Rampersad, Hughes was also contacted by the Writers’ War Board, which sought radio programming to promote unity and prevent further racial violence. Hughes responded with some songs and two short plays, In the Service of My Country and Private Jim Crow. While the former was broadcast on WNYC and praised, the latter—more critical in its depiction of discrimination faced by Black soldiers—was never aired anywhere. Hughes himself acknowledged the difficulty of such material, noting radio’s persistent censorship of dramatic treatments of Black life.

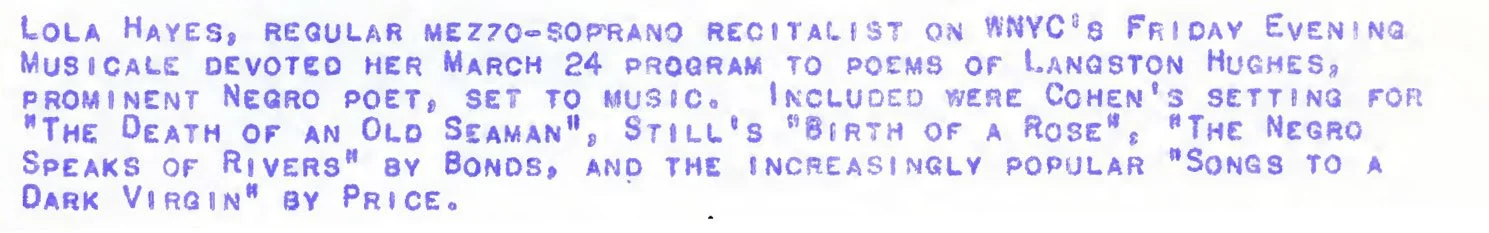

Hughes returned to WNYC in 1944 as a guest on mezzo-soprano Lola Hayes’s weekly program Tone Pictures of the Negro in Music, which highlighted African American composers and their work. The November 29 broadcast focused on musical settings of Hughes’s poetry, and he read from his opera Troubled Island. Other guests during the program’s run included Abbie Mitchell, Will Marion Cook, Hall Johnson, and Clarence Cameron White.

Portrait of Lola Hayes in 1941 by James L. Allen/Courtesy of The New York Times.

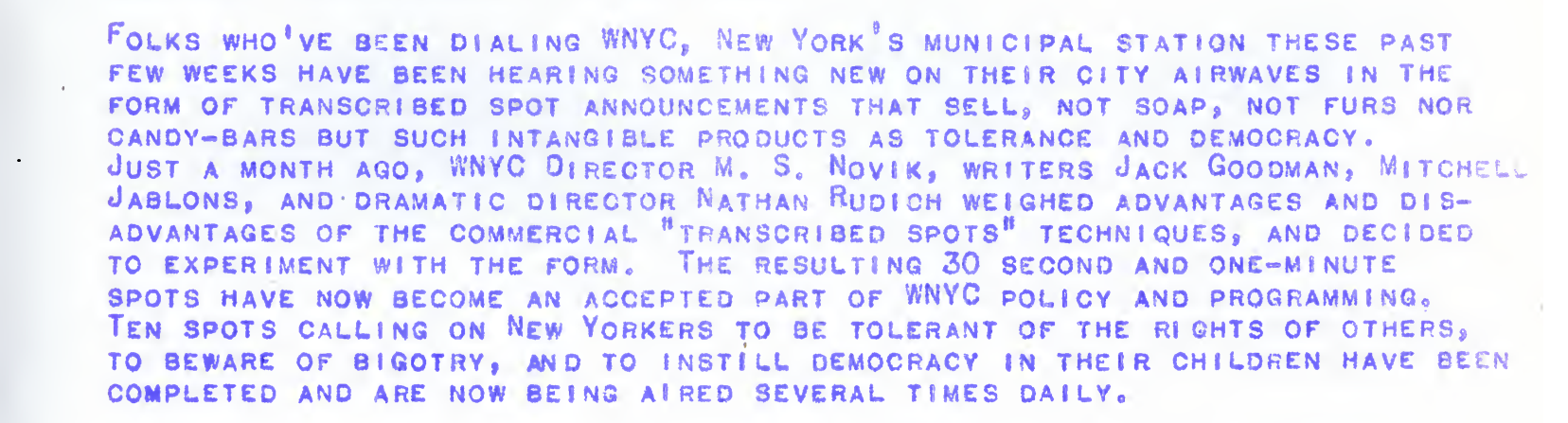

NAEB Newsletter April 1, 1944. Excerpt courtesy of Unlocking the Airwaves/University of Maryland.

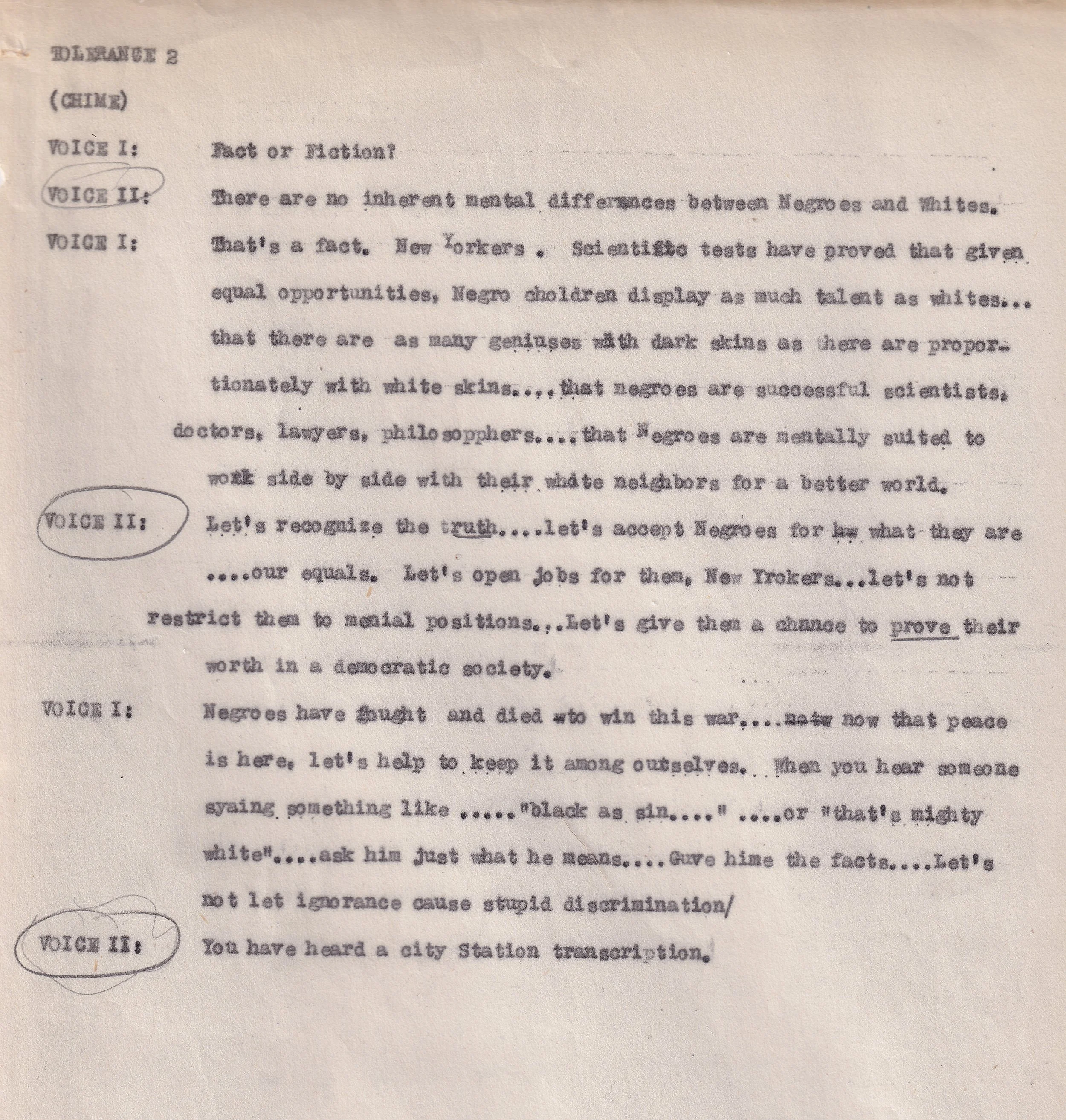

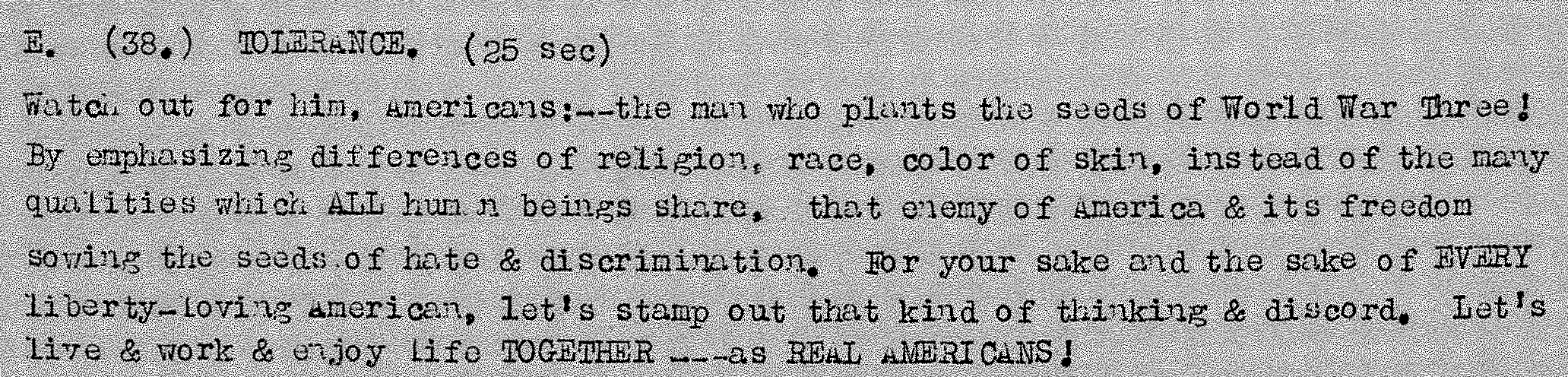

In February 1944, Billie Holiday made a late addition to WNYC’s annual American Music Festival, appearing in a swing session alongside Hot Lips Page and Coleman Hawkins. The following month, WNYC also began airing spots against bigotry as part of director Morris Novik’s vision of public radio to educate for democracy.

NAEB Newsletter April 1, 1944. Excerpt courtesy of Unlocking the Airwaves/University of Maryland.

Script for a spot on tolerance from 1944. WNYC Archive Collections.

On April 2, 1944, Mayor La Guardia welcomed composer and baritone Harry T. Burleigh to City Hall for a broadcast of Talk to the People, continuing the station’s engagement with African American cultural leadership during the war years.

(Audio from the Municipal Archives WNYC Collection)

1936 portrait of Harry T. Burleigh by Maud Cuney-Hare, 1874-1936/Wikimedia Commons.

The year 1944 saw the municipal station move away from biodramas toward short-lived serial dramas that aimed to portray African Americans as everyday Americans who happened to be Black. On Saturday evenings in June, an all-Black cast appeared in I’m Your Next Door Neighbor, which followed the business and home life of a “typical” New York family living in Harlem. Station director Morris Novik explained that “tolerance and prejudice were not the theme of the series, but during the course of normal events it brought home to the listener that there were certain evils that perhaps he was not aware of previously.”

In an article about the “falling color bar” in radio, The Chicago Defender called the program “the most advanced program artistically.” The paper also quoted producer Barbara M. Watson, who said, “It is most important that young Negroes look to radio as the future. There are inroads to be made now. It will be tougher later.” Watson went on to have a distinguished career, becoming the first African American and the first woman appointed Assistant Secretary of State.

Josh White at Café Society circa 1946 by William P. Gottlieb/Library of Congress.

The second serial drama was Henry Allen—American. Airing on Sundays from October into November 1944, the program was a takeoff on Henry Aldrich, the popular white protagonist of NBC’s The Aldrich Family. Like I’m Your Next Door Neighbor, the series sought to normalize Black domestic life. An announcement in The Brooklyn Eagle said the program would “try to give us an understanding glimpse into the homes and hearts of 14,000,000 fellow citizens.”

Folksinger Josh White performed at the February 1945 American Music Festival. The announcer described his repertoire as “music that is rooted in the soil and the heart of the American people,” and quoted Langston Hughes, who called White “a fine singer of anybody’s songs—Southern Negro, Southern white, plantation work songs, modern union songs, English or Irish ballads—any songs that come from the heart of a people.”

Audio courtesy of Smithsonian Moe Asch Collection.

The following month, President Franklin D. Roosevelt died, and the NAACP mounted an extensive tribute over the municipal station. On April 15, listeners heard from attorney Herman Taylor, Roy Wilkins, NAACP president Arthur B. Spingarn, and Maude Turner of the New York City NAACP branch. Spingarn said, “The death of President Roosevelt is a tragic loss to mankind. But to minority peoples of the world—particularly the minority groups in this country—it is an irreparable calamity.”

Returning from Army service, producer and host Clifford Burdette launched Freedom’s Ladder in July 1946. The weekly program blended music and civil rights advocacy and was described as “the only weekly program battling discrimination and prejudice.” Echoing the mission of his earlier WNYC series Those Who Have Made Good, Burdette told the Baltimore Afro-American, “Our show aims to entertain and to promote the idea that everyone has a chance to climb freedom’s ladder. You’ve got to be good, and you’ve got to work at it.”

The program ran for a year and featured some nationally known performers, including Nat King Cole and Sarah Vaughan, but largely relied on entertainers from Harlem nightclubs and other local venues, along with frequent appearances by members of the New York State Commission Against Discrimination. Unlike Burdette’s earlier program, the high-powered roster of Harlem Renaissance celebrities was largely absent. New York Amsterdam News columnist and radio host Bill Chase was a regular presence and shared hosting duties.

(Audio from the Municipal Archives WNYC Collection.)

On April 16, 1946, municipal radio listeners heard NYU sociologist Dr. Dan Dodson moderate a panel discussion titled “How Can We Work for Interracial Understanding?” Panelists included pioneering African-American psychologist Dr. Kenneth B. Clark, Judge and civil-rights attorney Hubert Delany, and journalist and social historian Dr. Albert Deutsch. Later that spring, on June 3, listeners may also have caught a live broadcast of Billie Holiday performing at Jazz at the Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall.

Kenneth B. Clark, Judge Hubert T. Delaney, Dr. Dan Dodson, and Mr. Albert Deutsch during broadcast of WNYC radio show, “How can we work for interracial understanding?” Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

One More River producers Bill Chase and Ken Joseph in front of the microphone circa 1947. WNYC Archive Collections.

From January 10 to April 6, 1947, One More River was billed as “the only radio show in the country produced by a Negro–White team” dedicated to improving race relations. The Sunday broadcast was produced by New York Amsterdam News columnist Bill Chase and WNYC staff announcer Ken Joseph, who said the program was “dedicated to the equality and dignity of all men” and sought to expose prejudice in both the North and the South. The series combined dramatizations and music, with guests including Teddy Wilson, Kenneth Spencer, Jenny Powell, Mildred Bailey, Lillette Thomas, Melba Allen, the Ellis Larkins Trio, and the Al Casey Trio. The Nameless Choir appeared regularly under the direction of Charles King. This is the April 6, 1947 program from the Municipal Archives WNYC collection.

African-American conductor Dean Dixon led the American Youth Symphony in February 1947 for the eleventh WNYC American Music Festival concert. The program featured contralto Carol Brice, with pianist Vivian Rivkin, and included works by William Schuman, Johan Franco, Norman Dello Joio, and Richard J. Newman. The concert concluded with Newman’s United Nations Cantata for Chorus and Orchestra, performed by the David Randolph Chamber Chorus.

On June 29, 1947, WNYC carried President Harry S. Truman’s address to the NAACP at its thirty-eighth annual conference. The Lincoln Memorial speech was the first time a sitting U.S. president spoke to the organization’s annual meeting.

https://www.wnyc.org/story/president-truman-at-naacp-38th-annual-meeting/

(Audio from the Municipal Archive WNYC Collection.)

President Truman delivering remarks to the NAACP at the Lincoln Memorial, June 29, 1947. Photo courtesy of the Truman Library.

The Thelonius Monk Quartet performed at the ninth American Music Festival on February 16, 1948. Monk was joined on piano by trumpeter Idrees Sulieman, bassist Curly Russell, and drummer Art Blakey. Their set included the standard All the Things You Are.

https://www.wnyc.org/story/52583-past-present-thelonious-monk-quartet-1948

Audio from the WNYC Archive Collections.

Jazz Classroom of the Air premiered on October 9, 1948. The thirty-minute broadcast accompanied an NYU jazz course taught by John Hammond of Mercury Records and George Avakian of Columbia Records. Designed as both public educational entertainment and a supplement to the university course, the program paired Saturday evening broadcasts with Monday classroom lectures. The inaugural episode traced the origins of jazz and featured several early recordings, including one by a young Louis Armstrong.

(Audio from the WNYC Archive Collections.)

Civil rights leader Walter White spoke at the Cooper Union Forum on December 18, 1949. His address, “The Race Problem in the United States,” examined the relationship between race and foreign policy and was carried live from the Great Hall over WNYC.

(Audio from the Municipal Archives WNYC Collection.)

Conclusion

Taken together, these early decades of New York’s municipal broadcasting reveal WNYC as an imperfect but often pioneering civic platform for Black cultural expression, political debate, and historical self-representation. At a time when commercial radio routinely excluded African-American voices—or confined them to caricatures—the city-owned station repeatedly created space for Black artists, intellectuals, activists, and institutions to speak in their own voices and on their own terms. These efforts unfolded unevenly, shaped by the limits of the era, wartime pressures, censorship, and persistent racial inequities. Yet they also reflected a sustained belief that public broadcasting could serve democratic ends by broadening who was heard and what was heard.

From early policy decisions banning racial epithets, to landmark series such as Native Sons and Those Who Have Made Good, to wartime appeals for unity and postwar explorations of everyday Black life, WNYC’s programming documented—and at times anticipated—larger national conversations about race, citizenship, and cultural authority. The station’s airwaves carried music, drama, and debate that challenged prevailing stereotypes and introduced audiences to a fuller, more complex vision of African-American life in the United States.

As WNYC moved beyond its first quarter-century, these broadcasts formed a foundation on which later generations would build. The preserved recordings remain vital historical evidence of how New York City’s municipal radio, at its best, functioned as a forum for inclusion, education, and civic responsibility—an aspiration that continues to resonate during Black History Month and beyond.

Anti-bigotry spot from 1946. WNYC Archive Collections.

___________________________________________________________

DeVeaux, S. (1993). “Black, Brown and Beige” and the Critics. Black Music Research Journal, 13(2), 125–146. https://doi.org/10.2307/779516

March 3, 1945 pg. 9 Chicago Defender Natil. Ed.