On November 25, 1878, Richard Plunkett wrote to a Mr. W. D. Sloane from his jail cell in “The Tombs” prison. “I will once again appeal to you for mercy not for myself but for my poor old father & mother who is on the brink of the grave and for my poor wife and two little children all of whom with yourself I have so cruelly wronged.” In another missive from his cell on the same day, he added with regard to his wife and children, “I don’t know what will become of them I suppose they will go to the poorhouse.”

“The Tombs” Prison with its distinctive “Egyptian” motif entrance, ca. 1880s. DeGregorio Lantern Slide Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The letters, and other documents can be found in the New York District Attorney’s felony prosecution file, Peo. v. Richard Plunkett, November 14, 1878. According to the Bill of Indictment, the Grand Jury indicted Mr. Plunkett for “Embezzlement and Grand Larceny” of money from the firm of W. & J. Sloane. The file included evidence in the form of a check made payable to “R. Plunkett” for One Thousand Sixty-Four Dollars,” [equivalent to about $30,000 currently] dated October 29, 1878, drawn on the Bank of New York.

In one of his several letters to the Sloane brothers, proprietors of the firm, Plunkett explains, “Mr. Sloane whatever money I took it was not to hoard up... if that was the case I could have taken tens of thousands; no, it was only when I had no money to satisfy my thirst for rum.”

Letter to W. D. Sloane, from Richard Plunkett, page 1, November 25, 1878. New York District Attorney Indictments Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Letter to W. D. Sloane, page 2. New York District Attorney Indictments Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

These letters, and many thousands of similar documents, are found in the New York District Attorney’s closed case file collection, one of the series of records pertaining to the administration of criminal justice in the Municipal Archives.

Beginning in 1990, the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) awarded grant funds to the Municipal Archives for several projects to ensure long-term preservation and provide greater access for selected series in the collection. The types of material include docket books, minutes of court proceedings, and case files. They currently total more than 20,000 cubic feet, and date from 1684 through the 1980s.

Bill of Indictment, for “Larceny of Money & Etc. from the Person in the Night,” with notation of conviction, 1878. New York District Attorney Indictments Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Among the preservation projects, the Endowment supported indexing the New York District attorney’s felony indictments from 1879 through 1894. Creation of that index greatly expanded the utility of the series for social historians and other researchers. The Archives is currently continuing the indexing effort, beginning with cases filed in 1878 and working in reverse chronological order.

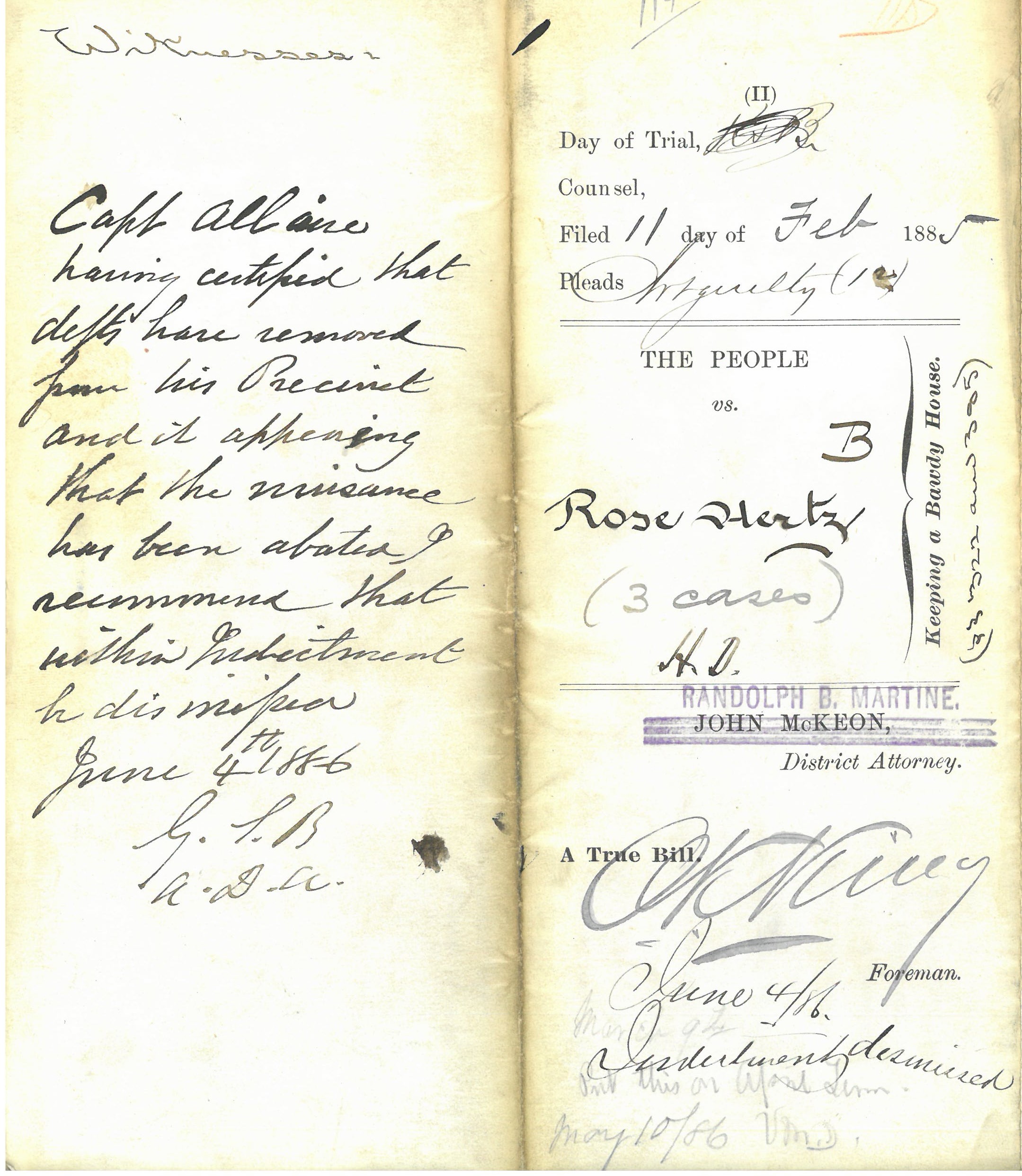

The records being indexed consist of the “files” or papers, produced over the course of the felony indictment process. Each file pertains to a particular defendant accused of a felony. The case files generally include three types of documents: 1) the grand jury indictment (a “bill” of indictment), signed by the foreman; 2) documents generated by the lower courts—police or magistrate’s—including the defendant’s plea; and 3) supporting documents including witness statements, coroner’s inquests, photographs, newspaper clippings, correspondence, diaries, marriage certificates, business cards, and bankbooks.

Plea Statement, Police Court, 1878. New York District Attorney Indictments Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The first document in most case files is the formal indictment; it serves as a cover sheet for the succeeding items in the file. It typically reads, “The People vs.... [name of defendant]” and lists the alleged offense, name of counsel, date of indictment, name of district attorney, and whether or not the defendant has been bailed. It is signed by the foreman of the grand jury. There is usually a notation indicating the trial outcome, e.g. “tried and acquitted” or, “convicted” and sometimes if convicted, the sentence, e.g. “S.P. (State Penitentiary), 10 years.” The indictment also includes a full account of the alleged criminal offense; for more routine crimes, this usually consists of a printed form where the clerk simply fills in the name of the defendant. Otherwise, it is a very detailed written statement.

The file includes various documents generated during the arraignment process in the police court. They comprise the original “complaint” filed by a police officer, the victim of the crime, or an officer of an organization such as the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. The forms detail the names of the police court justice, arresting officer, court clerk, and witnesses. Other papers provide detailed information as to the time, place, and circumstances of the offense. These documents provide the rich descriptive information that researchers often find the most rewarding.

The lower court documents also include the defendant’s plea statement. The form consists of a series of questions that the clerk would ask of the defendant: “What is your name? How old are you? Where were you born? Where do you live? What is your occupation?” And finally, “Have you anything to say, and if so, what relative to the charge here preferred against you?” The answer is usually “I am not guilty.” The court clerk records the answers and the defendant signs the document, or makes an “X” if unable to write.

Bill of Indictment, for “Arson” with notation of circumstances and dismissal, 1878. New York District Attorney Indictments Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The types of cases found in this series include indictments for more than seventy felony offenses ranging from abandoning a child to voting illegally and every other possible felony: bigamy, fraud, libel, homicide, rape, forgery, arson, poisoning, rioting, embezzlement, kidnaping, perjury, and keeping a disorderly house, to name a few. The more routine larceny, assault, and robbery are very well represented.

Letter to District Attorney, in Peo. v McCoy, 1878. New York District Attorney Indictments Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Thanks to widespread availability of digitized newspapers, combined with the felony indictment index database, patrons can now access case files that previously would have been exceedingly difficult to identify. Armed with the name of a defendant and a date of the criminal transgression (usually from a newspaper article), these patrons are rewarded with unique and detailed information.

For family history researchers, it is not necessarily the criminal offenses that are of interest, but rather the other details about the defendants, their families, residences, occupations, possessions—information typically found in the files—that is so valuable and not available from any other source.

The large quantity of these records suggests that criminal activity was a significant and unfortunate fact of life in New York City at that time. However, the records which are the written legacy of that world now provide a windfall for scholars and other researchers as they seek to illuminate the past.

What may not be evident from this description of the records is the level of detail concerning daily life illuminated by the written account of the circumstances of a crime. The description also does not convey the emotions and passions that are revealed in the records. Many attachments in the files, such as letters from family and friends to the district attorney or the courts, are poignant and telling.

Check, evidence in Peo. V. Plunkett, 1878. New York District Attorney Indictments Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Returning to Mr. Plunkett, the notation on the Bill of Indictment indicates that he pled guilty to Grand Larceny and was sentenced to the penitentiary for two years. One additional document in the file, dated October 7, 1879, Albany, N.Y. from the New York State Executive Chamber to the New York District Attorney provides further evidence of the outcome. The letter stated that an application had been made to the Governor for the “Pardon of Richard Plunkett” and requested the District Attorney to furnish to the Governor “…with a concise statement of the case as proven on the trial, together with any other facts or circumstances which may have been a bearing on the question of granting or refusing a Pardon.” There is not any documentation in this file on whether the pardon was granted.

The drama of Mr. Plunkett’s predicament and those of the many thousands of other defendants in the Municipal Archives’ collections are unique records that in many instances are the only extant documentation of that person’s existence. Given the value of this series the Municipal Archives believes devoting resources to expanding access is a worthwhile endeavor.