There has been much speculation in recent months concerning whether President Joe Biden’s infrastructure projects and related programs, if given the green light, would prove as transformative for the nation as President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal was in the 1930s.

A life-long swimmer, Parks Commissioner Robert Moses vastly expanded access to aquatic facilities for New Yorkers. In 1936, he opened ten new swimming pools and during his long tenure he built and improved public beaches throughout the city. “Swim” original art for subway. Tempura water-color on tissue paper, 1937; artist unknown. Department of Parks General Files, 1937.

There is no question, however, that the New Deal transformed New York City. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) was the capstone of Roosevelt’s efforts to recover from the Great Depression. Established as part of the Emergency Relief Appropriations Act of 1935, the WPA was the largest jobs initiative in American history. When the federal funding for the WPA became available, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia persuaded Roosevelt to release billions of dollars for construction projects. It was a partnership that would forever change the city.

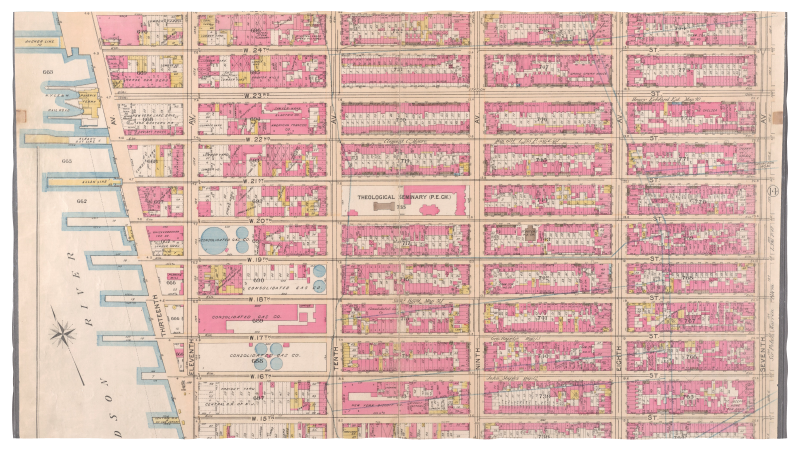

New York received more federal funds than any other city in the nation and employed more than 700,000 people through the Depression years. They built or renovated schools, bridges, parks, hospitals, highways, airports, stadiums, swimming pools, beaches, hospitals, piers, sewers, libraries, courthouse, firehouses, markets and housing projects throughout the five boroughs. The Triborough Bridge, the Holland and Lincoln Tunnels, the FDR Drive, the Henry Hudson and Belt Parkways, and the New York Municipal (LaGuardia) Airport are just some of the WPA-funded projects that have served New Yorkers over the past eight decades.

To the eternal benefit of generations of historians and researchers, the Archives holds extensive collections essential for exploring the New Deal in New York City.

Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia to Harry Hopkins, Administrator Works Progress Administration, Postal Telegram, May 19, 1936. Fiorello LaGuardia Collection, subject files. NYC Municipal Archives.

Documenting the New Deal in the city is largely a tale of two remarkable New Yorkers: Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia and ‘master builder’ Robert Moses. Archival records showing their influence and impact on the city total more than 1,500 cubic feet.

Of particular interest to New Deal historians are Mayor LaGuardia’s subject files. There are 27 folders with content specifically labeled as relating to the WPA. In addition, there are files pertaining to all of the public works construction projects–housing, highways, parks, swimming pools, etc., as well as the Civilian Conservation Corps, and other New Deal programs such as Social Security. In addition, there is a separate series of correspondence with federal officials in Washington D.C. totaling five cubic feet. Not all of it specifically pertains to the WPA, but given the importance of the various programs and the billions of dollars flowing from Washington, information about the massive federal program is well represented in the correspondence.

Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia to Miss Sue Ann Wilson, Federal Theatre Project, November 24, 1936. Fiorello LaGuardia Collection, correspondence with federal officials. NYC Municipal Archives.

LaGuardia’s records have been available at the Municipal Archives since its founding in 1952. The Robert Moses collection is a more recent addition. In 1984, city archivists visited a Department of Parks and Recreation storage facility at the Manhattan Boat Basin under the Henry Hudson Parkway, where they discovered 800 cubic feet of material—about 400,000 items—from 1934 through the 1970s, that included an extensive record of the WPA-funded projects during Moses’s long reign as a New York power broker. LaGuardia appointed Moses as Commissioner of the Department of Parks in 1934 and he served in that capacity until 1960, during which time he also held at least a dozen city and state positions.

79th Street Boat Basin, Henry Hudson Parkway, ca. 1937. Municipal Archives Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

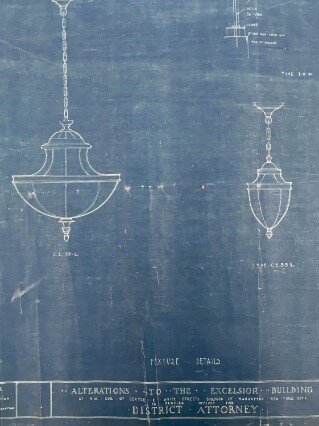

The records found at the Boat Basin were in remarkably good condition, consisting of carbons or originals of Moses’s correspondence, memoranda, transcripts, reports, contracts, news clippings, maps, blueprints, plans, printed materials, press releases, invitations, and photographs. There are 121 folders specifically labeled “WPA,” in the “General Files,” series but, similar to the LaGuardia papers, Moses’ correspondence relevant to New Deal programs are evident throughout the collection.

No detail was too small or building too insignificant for Moses and his talented team of architects as illustrated by the handsome design of this concession stand and comfort station. Pelham Bay Park, October 22, 1941. Department of Parks Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The third trove of WPA-related materials in the Archives is the WPA Federal Writers’ Project collection. The WPA did not just improve parks and build roadways—a portion of the money was set aside for unemployed professionals in the “arts.” As WPA director Harry Hopkins explained, “they have to eat like other people.” It was called Federal Project Number One, and consisted of Art, Music, Theatre and Writers’ Projects. The Federal Writers' Project (FWP) was the only one to operate in all 48 states and the territories of Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands, as well as New York City. At its peak, in April of 1936, there were 6,686 on the payroll nationwide; approximately 40% were women.

Triborough Bridge, December 1937. WPA Federal Writers’ Project Photograph Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

New York City housed the largest FWP Unit, employing nearly 300 people. The writers produced the New York City Guide, New York Panorama, Almanac for New Yorkers, a number of ethnic studies, Who’s Who in the Zoo—a total of 64 proposed books. The New York City Guide proved so durable and popular that it was re-published in 1966, 1982 and again in 1992. To illustrate the books, the NYC unit acquired photographs from trade organizations, other branches of Federal Project One, and sent staff photographers to document many aspects of New York City.

Feeding the City, reference materials, brochure, ca. 1937. WPA Federal Writers’ Project Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Two years ago, a manuscript and research files from this collection documenting the consumption and preparation of food in the City were showcased in an exhibit Feeding the City at the Municipal Archives.

Manhattan approach to the Holland Tunnel, December 6, 1936. WPA Federal Writers’ Project Photograph Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Shortly after the commencement of World War II hostilities, the WPA discontinued Federal Arts programs around the country and many shipped their records to Washington, D.C. (most went to the Library of Congress). The records of the NYC Unit of the Writer’s Project did not leave the City, however. They were deposited in the Municipal Library. Although there is not extant documentation to confirm this, it seems likely that the FWP staff had been regular patrons of the Municipal Library and well known to long-time Library Director Rebecca Rankin. Perhaps she suggested that her Library would provide a good home to their records. And indeed it did; the FWP collection (eventually transferred to the Municipal Archives) has served as a rich research resource for many decades.

Bookbinder. WPA Miscellaneous Projects, Bookbinding, ca. 1937. WPA Federal Writers’ Project Photograph Collection. Photographer: Ralph DeSola (Federal Art Project). NYC Municipal Archives.

WPA instructors held classes in designing and staging puppet shows, Tompkins Square Boys Club, January 1937. WPA Federal Writers’ Project Photograph Collection, Photographer: von Urban (Federal Art Project). NYC Municipal Archives.

The photographs in the collection are of particular relevance to documenting what the WPA accomplished in New York City. The FWP staff arranged the pictures by subject, e.g. “Bridges, Triborough Bridge,” or “Transportation, Tunnels.” “WPA Activities” was another subject heading and reviewing the list of sub-headings provides an indication of the wide scope of the WPA: construction projects, music project, nursery schools and parent education project, puppet teaching project, sewing project, theatre project, etc.

It is too soon to know whether President Biden’s proposed programs will have the same transformative effect as the New Deal. But if a model is needed for a successful economic recovery with a lasting impact, one need look no further than New York City.

Portions of this article appeared in The Living New Deal an organization dedicated to research, presentation and education about the immense riches of New Deal public works.