“A List of the Members of the City Government from its incorporation (1653) up to the present time, arranged alphabetically; with the different stations held by them in the Common Council; and also under the State and United States Government.” Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York, 1866. D.T. Valentine, Clerk of the Common Council.

Recent news reports have suggested that New York City has been misnumbering its Mayors since the 1600s. Not that they were numbering them at that time, but ever since the City started giving official numerical designations, the numbering has gone awry.

In the 2019-2020 “Green Book,” The Official Directory of the City of New York, Matthius Nicolls is given a single entry, 1672. In truth he was Mayor from 1671-1672 and again from 1674-1675. NYC Municipal Library.

This past August, historian Paul Hortenstine noticed that the “Official” list of Mayors failed to include the second term of Mayor Matthias Nicolls (Nicoll). He had served two non-consecutive terms, the first from 1671-1672, and the second from 1674-1675. Hortenstine was not the first to notice this discrepancy. In 1989, the New York Genealogical and Biographical Society published an article by Peter Christoph revealing that every mayor after #7 had been misnumbered. As Christoph pointed out, if a Mayor had two non-consecutive terms the practice was to assign them two numbers, starting with Thomas Willett, who was Mayor #1 and #3. He noted four other early Mayors credited with two terms.

We thought the error might have been due to a little-known hiccup in mayoral history. In July 1673, the Dutch (who had established the colony of New Amsterdam in 1625 and lost it in 1664), invaded and took it back. For fifteen months the colony (renamed “New Orange”) was under a Dutch “Council of War,” that restored the Dutch-style government of a council of Burgomasters and Schepens. As a result, there was not a “Mayor of New York” between July 1673 and November 1674, when the English Governor, Edmund Andros, reappointed Nicolls. Moreover, Nicolls had not been Mayor when the Dutch invaded, his successor, John Lawrence, had assumed that role. So, by all rights, Nicolls served two non-consecutive terms with another Mayor in the middle, making him Mayor #6 and #8. Thereby moving everyone else one place down the line. Lawrence was appointed Deputy Mayor in 1674, but also served another non-consecutive term as Mayor, the 2nd time in 1691, making him both #7 and #20 (under the corrected numbering system).

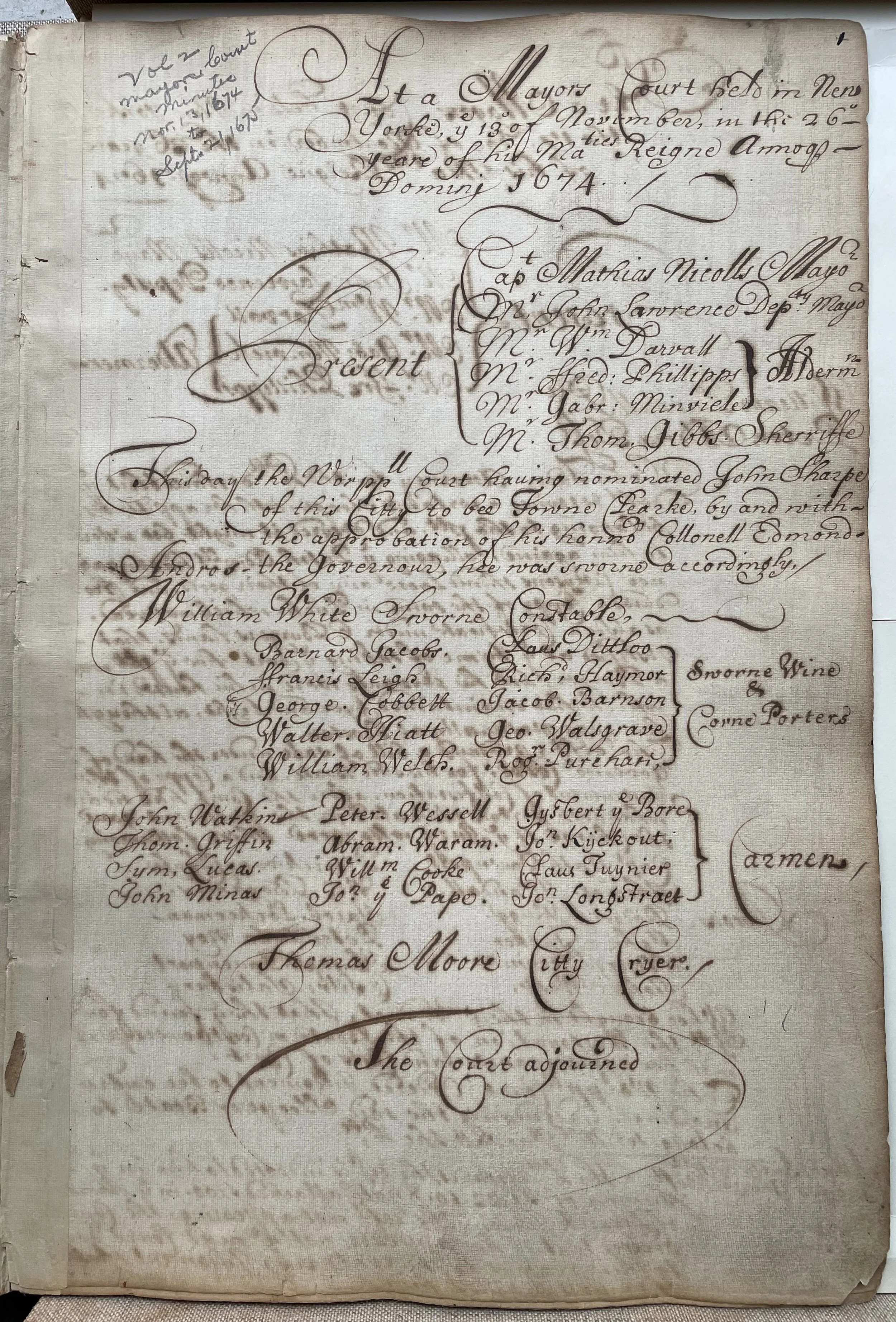

Records of the Mayor’s Courts of the City of New York, entry from October 12, 1672 lists “Capt. Matthius Nicolls, May[or].” The book for the following year is missing from the historic record. Court Minutes, Volume 6, 1670 October 13-1674 November 10, NYC Municipal Archives.

On October 12, 1672, the council put forward John Lawrence and Matthius Nicolls as candidates for Mayor. John Lawrence was apparently selected but those records have been lost. MSS0040 New Amsterdam records, Court Minutes, Volume 6, 1670-1674, page 205.

In one of his last acts as City Clerk, David Dinkins transferred the colonial Dutch and English records of New Amsterdam and New York to Commissioner of the Department of Records & Information Services, Eugene Bockman, December 30, 1985. NYC Municipal Archives.

Christoph, in a footnote, surmised the error arose from the compiler using the “Minutes of the Mayor’s Court” as a source, and noted that a volume for the period November 1674-September 1675 had been missing for some time. In 1982, historian Kenneth Scott located the volume at the New York County Clerk’s Division of Old Records. At that time, all the earlier Dutch and English Court minutes resided with the New York City Clerk. On December 30, 1985, outgoing City Clerk David N. Dinkins transferred the entire collection of colonial-era records held by the City Clerk to the Municipal Archives. The 1674-1675 volume still resides with the County Clerk in a later series of Mayor’s Court records covering the years 1674 to 1820. However, the Minutes of the Common Council, which are also with the Municipal Archives and were published in 1905, still have a gap from 1674-1675.

After the Dutch returned New York to the English in 1674, the Mayor’s Court reconvened with Captain Matthius Nicolls as Mayor. Minutes of the Mayor’s Court, November 13, 1674-September 21, 1675. New York County Clerk.

There is yet another missing volume from these records—the volume documenting activities from October 13, 1672 to August 11, 1673. The last entry in the preceding volume, dated October 12, 1672, lists “Capt. Matthius Nicolls, May[or]” at the top. The next book in Archives possession starts on August 12, 1673, in Dutch, titled “Proceedings of the War Council of New Orange.” Those Dutch records end on November 10, 1674. The next volume begins, in English again, with Matthius Nicolls as Mayor. So, the first term of John Lawrence is missing entirely from the historical record. Some compiler must have realized this and inserted him into the history but forgot to split Nicolls’ two terms.

Proceedings of the War Council of New Orange, starts on August 12, 1673, in Dutch. The Dutch records end on November 10, 1674, just before Nicolls was reappointed. Court Minutes, Volume 6, 1670 October 13-1674 November 10, NYC Municipal Archives.

In the 1841 edition of the Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York, the clerk listed “Members of the City Council from 1655 to present.” The list actually starts at 1653 and included both Dutch and English governmental structures. Samuel J. Willis, Clerk of the Common Council, Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York, 1841. NYC Municipal Library.

The earliest printed list of Mayors (without numbers) that we located, appeared in the first Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York 1841-1842 edition, under the authority of Samuel J. Willis, Clerk of the Common Council. The list has large gaps in the colonial period and includes a note, “there are no records during the time of the first English possession in the Clerk’s office.” The Manual, as was explained in the preface, was created because it had, “been thought expedient to enlarge the substance of the City Hall Directory... by the introduction of additional matter interesting and useful to members of the Corporation....”

The first Manual listed “Mayors,” members of the City Council, and the Dutch colonial government officers of New Amsterdam. The Manuals became more widely associated with then Assistant Clerk and future Clerk, David Thomas Valentine. During D.T. Valentine’s tenure, from 1843 to 1867, the manuals became increasingly elaborate and lavishly illustrated with fold-out maps and historical information. He reprinted the 1841 list verbatim in the 1842-1843 edition. In the 1853 edition, Valentine included “Sketches of the Mayors of New York from 1665 to 1834.” This included all the colonial English Mayors but not the Dutch leaders. It does not mention Nicolls’ second term. This erroneous list was also published in the Civil List and Forms of Government of the Colony and State of New York beginning with the 1865 edition.

There were errors and large gaps in the first published list in 1841. It not only left out the 1674 second term of Nicolls, it identifies Thomas Willet as “Major” instead of “Mayor” in 1665 and then skips to the Dutch Burgomasters in 1673. Samuel J. Willis, Clerk of the Common Council, Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York, 1841. NYC Municipal Library.]

In the 1854, 1863, and 1866 editions of the Manual, Valentine printed an alphabetical “List of the Members of the City Government from its incorporation (1653) up to the present time...” This list included the Dutch but omits Mayor John Lawrence, an error repeated through the 1866 edition. In his 1861 Manual, Valentine also published a section called “Mayors of City,” which ignores the colonial period entirely. Instead, the list begins after the American Revolution with Mayor James Duane in 1783. The 1869 and 1870 editions contain something close to the current list of “Mayors of the City of New York” starting on 1665. However, they omitted two mayors.

“Mayors of the City of New York, 1665-1869.” Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York, 1870. John Hardy Clerk of the Common Council. NYC Municipal Library.

The earliest known appearance of a numbered list of the “Mayors of the City of New York.” Official Directory of the City of New York, 1921. NYC Municipal Library.

In 1918 the Official Directory of the City of New York, a.k.a. the “Green Book,” began publication under the direction of the Supervisor of the City Record. In 1921 the Green Book included a list of Mayors. In it, and all subsequent editions, until it went completely online in 2021, they reprinted and updated the list of mayors, with number designations. Up through 1936 the list was consistent. It started with Thomas Willett at #1 and finished with #98—LaGuardia. Then, starting in 1937, they added a mayor, Charles Lodwik as #21 (1694 to 1695) and bumped everyone after him up one so that LaGuardia became #99. Lodwik had also been missing from the 1869 and 1870 lists in the Manual, most likely the source for the Green Book. However, Lodwik (sometimes spelled Lodewick) had been included in the list of Mayors Valentine published in 1853 as “Charles Lodowick, Mayor in 1694.”

The insertion of Lodwik to the list in 1937 may originate with the 1935 publication of Select Cases of the Mayor’s Court as it contains two mentions of Mayor Charles Lodwik. The book also contains the first mention in print of Nicolls’ 1674 term. It states “The records of the Mayor’s Court included in this volume begin more properly with the reoccupation of the English in 1674. The new mayor and deputy-mayor, Matthias Nicolls and John Lawrence, respectively, had both held the mayoralty under the first English rule.”

Charles Lodowick, Mayor in 1694, was included in “Sketches of the Mayors of New York from 1665 to 1834,” but left out of later lists until 1937. Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York, 1853. D.T. Valentine, Clerk of the Common Council.

Additional confusion about the number of Mayors arises from the differing forms of government during the Dutch and English colonial periods. Until 1977, the City founding date was listed as 1664. In 1977, the founding date was set as “1625” to acknowledge the year the Dutch established a colony on Manhattan. Between 1625 to 1653 the colony was under the authority of the Dutch colonial governors. In 1653, New Amsterdam incorporated under a charter and established the Dutch system of Burgomasters and Schepens, and Schout, which could roughly translate to offices of mayors, aldermen, and sheriff. These bodies decided several different functions, including criminal and civil legal matters, and municipal governance.

On June 12, 1665, the English Governor Richard Nicolls (no relation) abolished the Dutch court and established the first Mayor’s Court, naming Thomas Willet as Mayor. Willet is traditionally listed as the first mayor.

However, even if the count begins in 1665, why does the list skip the new court of Burgomasters and Schepens appointed on August 17th, 1673? Part of the answer is that the Dutch system, with two or three Burgomasters (or Mayors) serving jointly is confusing. And as noted above, part of it is that the Dutch were largely written out of the history of New York City[i] until the 1970s. Given that the first English Mayors appointed by the Governor served functions similar to[ii] their Dutch predecessors, why not include the Burgomasters in the count? If the count included Burgomasters who served multiple, non-consecutive terms, 15 additional Mayors[iii] would be on the list.

List of the Burgomasters 1653-1674 as published in the Civil list and forms of government of the Colony and State of New York: containing notes on the various governmental organizations; lists of the principal colonial, state and county officers, and the congressional delegations and presidential electors, with the votes of the electoral colleges, 1870. Hathi Trust.

The aforementioned hiccup in 1673 was not the only period in which the line of Mayors was broken. Just over a hundred years later, on June 22, 1776, the line was interrupted again when the Continental Army arrested Mayor David Matthews. He escaped from house arrest in December 1776 and returned to New York, then under British military control. Matthews retained the title of Mayor with greatly reduced power. He left the City on November 25th, 1783 (Evacuation Day). The next Mayor was appointed on February 10, 1784.

Four “Acting Mayors” get mentions, but no numbers. Green Book 2019-2020. NYC Municipal Library.

Another oddity is that when Mayor James J. Walker was forced to resign due to a corruption scandal an “Acting Mayor,” Joseph V. McKee—President of the New York City Board of Aldermen—was appointed on September 1, 1932. In the subsequent special election, McKee lost to John P. O’Brien who served for one full year, 1933. O’Brien is on the list as #96, but although McKee is noted, he is not given a number. When William O’Dwyer left office in September 1950, Vincent R. Impellitteri, President of the City Council, assumed the role of Mayor. He is counted because he won the special election in November 1950 and served a full four-year term. McKee is not the only Acting Mayor who is not counted—Ardolph Kline finished William Gaynor’s term, after the latter died on September 10, 1913 of complications from an assassination attempt three years prior.

The Green Book records two additional instances, “T. Coman” in 1868, and “S.B.H. Vance” in 1874. They are on the list but are not counted as Mayors. Thomas Coman was President of the Board of Aldermen from 1868 to 1871. When Mayor John Thompson Hoffman left office to become Governor, Coman was elevated to Acting Mayor, serving from December 1, 1868, to January 4, 1869. The next Tammany-backed Mayor appointed him to oversee construction of the New York County (Tweed) Courthouse, and he was indicted for corruption. Samuel B.H. Vance similarly ascended to Acting Mayor from the position of President of the Board of Aldermen on November 30, 1874, when Mayor William Havemeyer died. He served until January 1, 1875, when William Wickman was sworn in. Exactly four weeks. No scandals recorded.

“Mayors of the City” was another list of mayors Valentine compiled that only included post-Revolutionary War mayors. Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York, 1861. D.T. Valentine, Clerk of the Common Council.

The count of Mayors in New York City government seems not to be determined by a uniform set of rules. Four Mayors who assumed the role by Charter mandate, but who were not elected, are not counted. In the colonial era, Mayors appointed by the English are counted. But not Dutch ones. Or “Acting” ones. Who makes up these rules?

Hortenstine has identified two additional colonial-era “Acting Mayors,” William Beekman from 1681-1683, who had been a Burgomaster in 1674, and Gerardus Stuyvesant in 1744. Neither has been listed in the Green Book and their dates in office overlap with other listed Mayors. The Municipal Archives’ finding aid to the Records of the Early Mayors, also has a numbered list of Mayors. It does not have Nicolls’ second term, or the two Acting Mayors Hortenstine identified, but it has another, Thomas Hood. Hortenstine believes that to be a transcription error however, and that it was Phillip French who assumed the office after Thomas Noell died from smallpox in 1702. The Archives list does assign numbers to Acting Mayors, and when last updated it had Bill de Blasio at #114. Adding the three missing terms, but subtracting Hood, he would be #116, making Adams #117 and Mamdani #118.

The initial question was, should Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani be counted as the 111th or 112th? But the answer has proven far more complex. The numbering of New York City “Mayors” has been somewhat arbitrary and inconsistent. Maybe he should be number 118? If the Dutch Burgomasters were counted in the same way we count Mayors serving non-consecutive terms, another fifteen would be included so the Mayor-elect might be number 133. There may even be other missing Mayors. As far as employees at the Department of Records and Information Services can tell, no government agency has been tasked with “counting” Mayors. The numbers have been more a matter of convenience. One thing for certain is he is not Mayor 111. By our current Anglo-centric numbering practice (not including Acting Mayors) it does appear that on January 1, 2026, Mayor Mamdani should be Mayor number 112.

[i] Valentine complained, in an 1867 letter, that the Dutch records “were not very attentively cared for, having been without readers for probably a century and more. No attempt had been made to translate them; and... the history of New Amsterdam... was not supposed to lie hidden in these dusty, unbound and forbidding volumes.”

[ii] It was not until the Dongan Charter of 1683 that City government more closely resembled our own, with a “common council” that consisted of a mayor, recorder, six aldermen, and six assistant aldermen. Most importantly, the Dongan Charter separated the legislative functions of the council from the two judicial courts that were established. However, the Mayor was still appointed by various governmental bodies until 1834 when Cornelius W. Lawrence was democratically elected Mayor. With the exception of Peter Delanoy who was democratically elected in 1689, during Leisler’s rebellion, a short-lived colonial uprising against Catholic English rule.

[iii] The Burgomasters were the following: 1653: Arent van Hattem, Martin Cregier; 1654: Arent van Hattem (replaced by Allard Anthony), Martin Cregier; 1655-1656: Allard Anthony, Oloff Stevenson van Cortland; 1657: Allard Anthony, Paulus Leendertseen van der Grist; 1658: Paulus Leendertseen van der Grist, Oloff Stevenson van Cortland; 1659: Oloff Stevenson van Cortland, Martin Cregier; 1660: Martin Cregier, Allard Anthony, Oloff Stevenson van Cortland; 1661: Allard Anthony, Paulus Leendertseen van der Grist; 1662: Paulus Leendertseen van der Grist, Oloff Stevenson van Cortland; 1663: Oloff Stevenson van Cortland, Martin Cregier, Paulus Leendertseen van der Grist; 1664: Paulus Leendertseen van der Grist, Cornelis Steenwyck; 1673: Johannes van Brugh, Johannes de Peyster, Ægidius Luyck; 1674: Johannes van Brugh, William Beeckman.

Sources:

American Legal Records—Volume 2: Select Cases of the Mayor’s Court of New York City, 1674-1784. Pp. 40-62. The American Historical Association, 1935. https://www.familysearch.org/library/books/viewer/854396/?offset=569061#page=55&viewer=picture&o=download&n=0&q=%22john%20lawrence%22

Andrews, William Loring: “David T. Valentine” reprinted in Valentine’s Manuals: A General Index to the Manuals of the Corporation of the City of New York, 1841-1870. Harbor Hill Books, 1981 (originally published 1900).

Christoph, Peter R., “Mattias Nicolls: Sixth and Eighth Mayor of New York.” The New York Genealogical and Biographical Society Record, July 1989: Volume 120, issue 3, pages 26-27. https://www.newyorkfamilyhistory.org/online-records/nygb-record/566-602/26

Civil List and Forms of Government of the Colony and State of New York: containing notes on the various governmental organizations; lists of the principal colonial, state and county officers, and the congressional delegations and presidential electors, with the votes of the electoral colleges. The whole arranged in constitutional periods. Weed, Parsons and Co., 1870. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009014294

Hortenstine, Paul. “NY City Mayors and Slavery: Matthius Nicolls: 6th & 8th.” 2025. Northeast Slavery Records Index. https://nesri.commons.gc.cuny.edu/matthias-nicoll-6th-and-8th/

Guide to the records of the Early Mayors, 1826-1897. NYC Municipal Archives. https://dorisarchive.blob.core.windows.net/finding-aids/FindingAidsPDFs/OM-EMO_REC0002_FA-MASTER.pdf

Valentine, David. T., et. al. Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York by New York (N.Y.). Common Council; 1841, 1853, 1861, 1866, 1870. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000054276