This past June 17, 2025, art historian and curator Bonnie Yochelson discussed her new book, Too Good to Get Married: The Life and Photographs of Miss Alice Austen on DORIS’ popular “Lunch & Learn” program. Yochelson’s biography explores Austen’s groundbreaking photography and how she challenged gender norms of her era. For those who missed the illustrated talk, it can be viewed on DORIS’ YouTube channel.

Staten Island Block 2830, Lot 49, 1940 “Tax” Photograph collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

This week, For the Record takes a journey through records in the Municipal Library and Archives that document Alice Austen (1866-1952), and her homestead in Staten Island. Located on bluffs overlooking New York Bay, the Gothic Revival cottage known as Clear Comfort is now in the portfolio of the New York City Historic House Trust. It has been fully restored and includes a museum dedicated to Austen’s work.

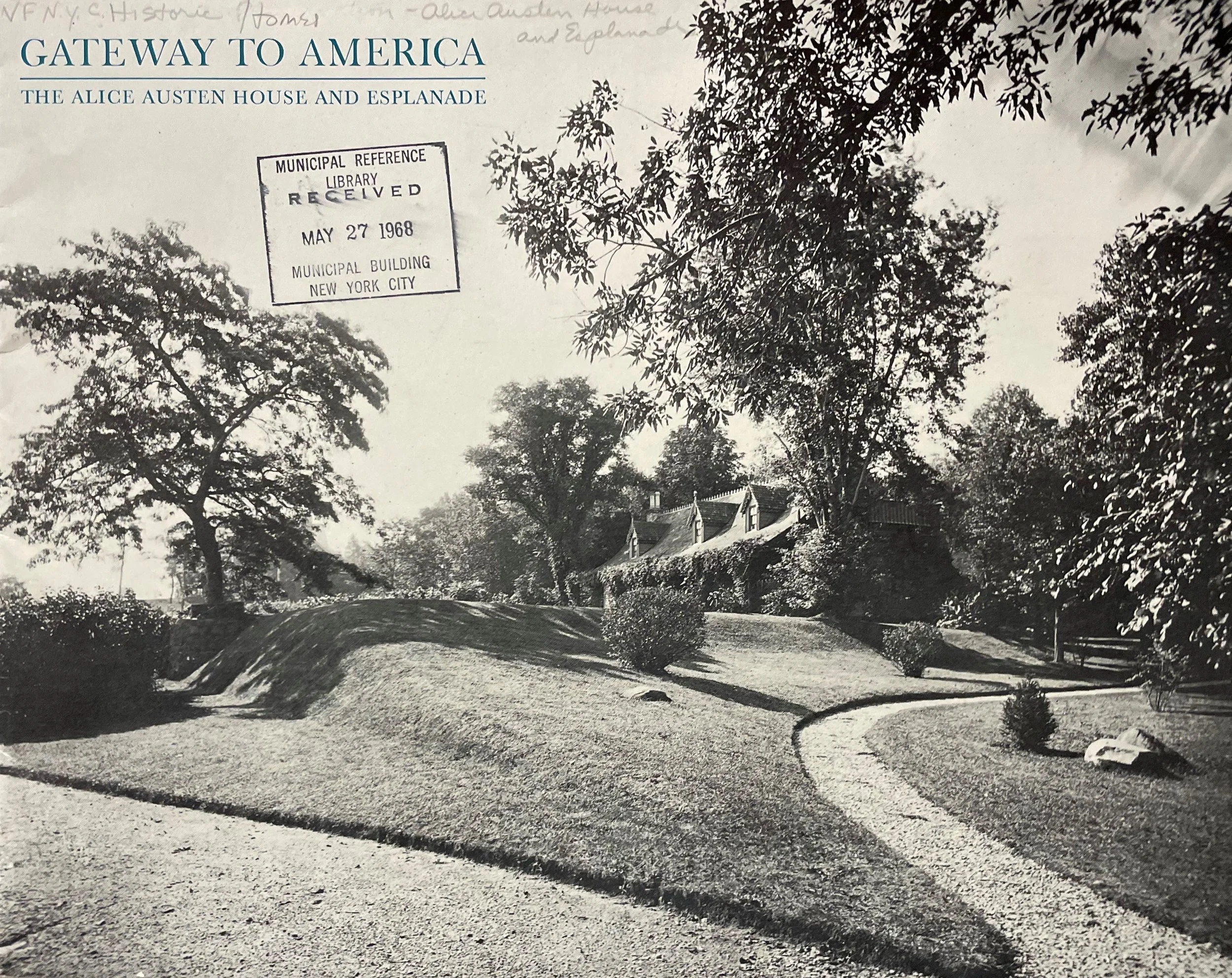

Researchers are often advised to begin their quest with the secondary sources available in the Municipal Library. And among them, the “vertical files” are particularly useful. Arranged by subject, they contain printed articles, unique ephemera and visual materials. Often cited in For the Record articles, the files did not fail to come through for information about Alice Austen, her house, and the history of its origins in the 17th century, near demolition in the 1960s, and full restoration in the 1980s.

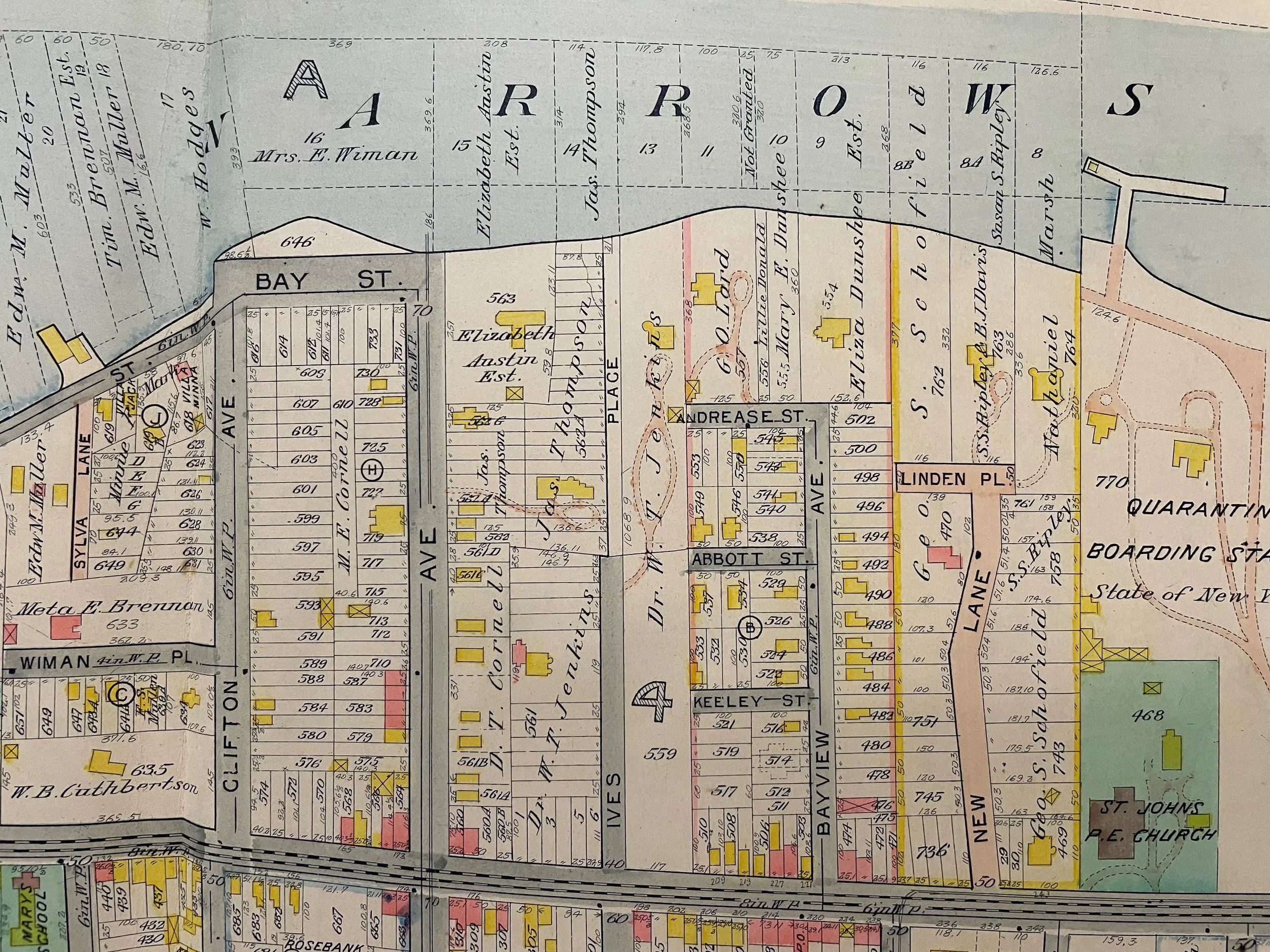

Robinson’s Atlas of Staten Island, 1907. NYC Municipal Archives

Elizabeth Alice Austen was born on Staten Island in 1866. At age two, she and her family moved into the nearby home of her grandfather, John Austen, where she lived until shortly before her death in 1952. Austen’s aunt introduced Alice to photography in the 1880s. Over the next fifty years, Austen created more than 7,000 glass-plate negatives and prints. Her images chronicled Staten Island, New York City, and particularly focused on the life of her friends and social circle. In 1917, her life partner, Gertrude Tate, joined Austen in the house where they remained until financial losses resulting from the Great Depression led them to lose the property in a bank foreclosure proceeding. Shortly before her death in 1952, an Austen photograph appeared on the cover of Life magazine and led to wider recognition of her talent. Austen’s photographs are now considered among the finest produced in America in the late 19th and early-20th centuries.

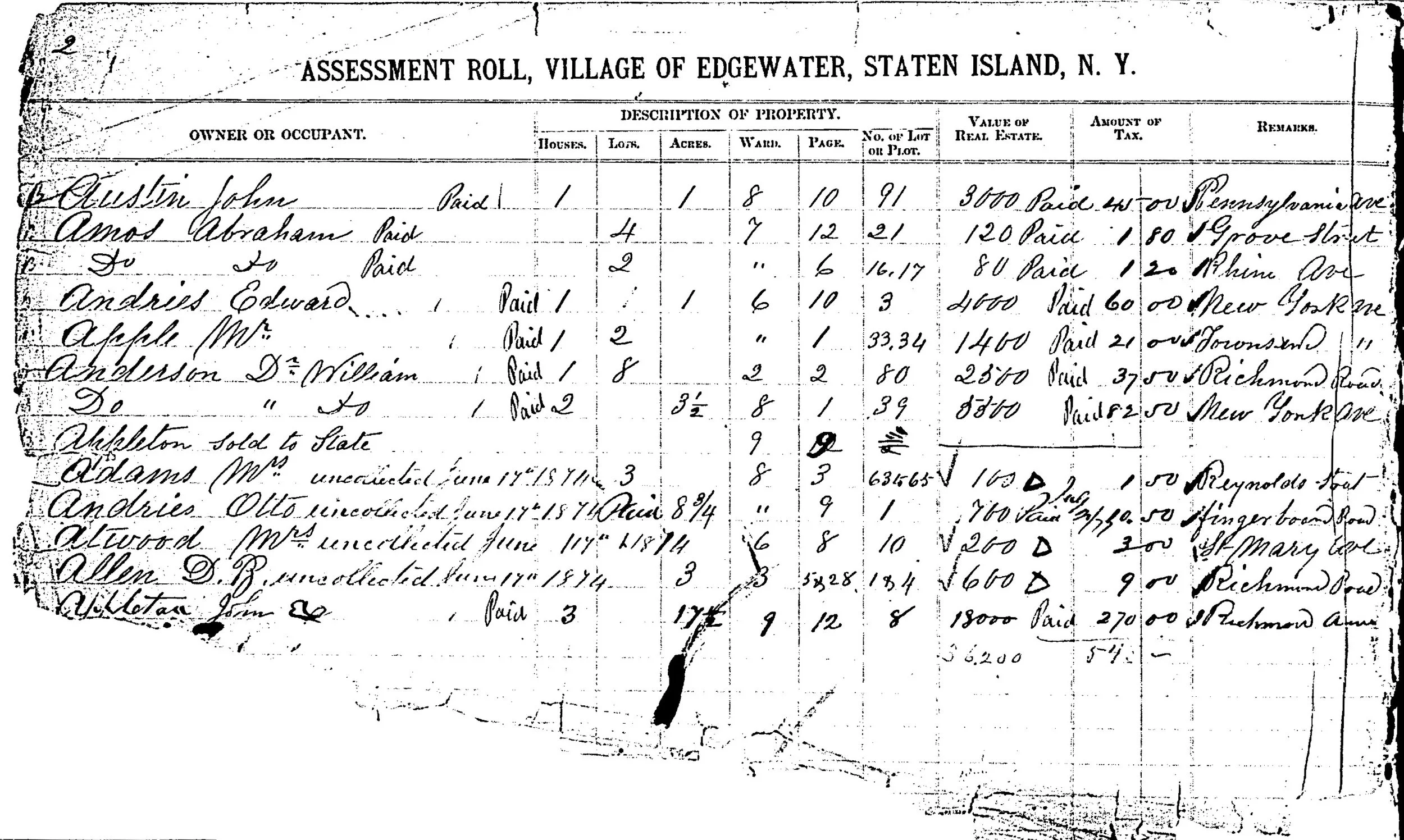

Assessed Valuation of Real Property, Town of Edgewater, Staten Island, 1873, “Old Town” Records collection. NYC Municipal Archives

Alice Austen’s grandfather John Austen purchased the family home in 1844. It had been originally constructed as a one-room farmhouse in the 17th century and went through many years of gradual additions and alterations. Austen transformed it to the Gothic Revival style recognizable today. The Library’s vertical file helps to tell the story. The New Yorker magazine printed a “Talk of the Town” article on September 30, 1967. The uncredited author described a visit to “a benefit punch-and-supper party being given by an organization called—with portmanteau clumsiness characteristic of so many ardent champions of good causes—Friends of the Alice Austen House and Esplanade.” At that time, according to the article, a real-estate syndicate owned the house along with two parcels of adjacent land that they intended to demolish to make way for a cluster of high-rise apartment buildings. The article described the house, “long, low-roofed, and engulfed in the leafy jungle of a long-abandoned Victorian garden,” surrounded by a “jumble of old barns and outbuildings in the shadow of an enormous horse-chestnut tree.”

Gateway to America, The Alice Austen House and Esplanade, Friends of the Alice Austen House and Esplanade, 1968, pamphlet. NYC Municipal Library.

As is often the case with vertical file contents, the “NYC Historic Homes - Alice Austen House and Esplanade” folder also included ephemera such as a copy of an illustrated pamphlet, Gateway to America: Alice Austen House and Esplanade, dated 1968, prepared by the Friends group, mentioned in the New Yorker article. It is interesting to note that the “Friends,” listed in the pamphlet turned out to be very prominent mid-century New Yorkers: photographers Berenice Abbott and Edward Steichen; architects Philip Johnson and Robert A.M. Stern; historic preservationists Margot Gayle and Henry Hope Reed, Jr., among others. VIPs who apparently saw the importance of preserving the Austen homestead also included Joseph Papp, Alfred Eisenstadt, and Cornelius Vanderbilt.

The Friends succeeded in having the Austen house designated as a Landmark in 1971. According to the Landmark Designation Report in the Library collection:

“On the basis of a careful consideration of the history, the architecture and other features of this building, the Landmarks Preservation Commission finds that the Alice Austen House has a special character, special historical and aesthetic interest and value as part of the development, heritage and cultural characteristics of New York City.... Accordingly,... the Landmarks Preservation Commission designates as a Landmark the Alice Austen House, 2 Hylan Boulevard.” [November 9, 1971]

Staten Island Block 2830, Lot 49, 1980s “Tax” Photograph collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The Alice Austen House and Esplanade, Friends of the Alice Austen House and Esplanade, n.s. pamphlet. NYC Municipal Library.

Soon after, in 1976, the City took title to the property, and in 1984 restoration of the house began. This information is gleaned from another item in the vertical files. An article in the Staten Island Advance, dated January 11, 1988, quoted Parks Commissioner Henry Stern’s remarks at a ceremony marking commencement of the restoration in 1984: “If we were dedicating this park because of the fabulous view, that would be enough. If we were dedicating the restoration of the house because it is a 17th-Century home of historical importance, that would be enough. If we were dedicating this house because of the brilliance of Alice Austen, that would be enough. But to have all these three things come together makes this an enormous event for New York.”

The history of the Austen House in the “Friends” brochure and other published sources provide the necessary dates to pursue research in the Municipal Archives collections. For example, the “Old Town” collection, recently processed and partially digitized with support from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission is one source. The ledgers in the collection had been assembled by the Comptroller shortly after consolidation in 1898. They consist of administrative and financial records from all the towns and villages newly incorporated into the Greater City of New York. Among them are the records of assessed valuation of real estate. Given the importance of revenue from property taxes it should not be surprising that the Comptroller made sure those records were preserved.

Maps and atlases in the Archives locate the Austen homestead in the Town of Edgewater. In the 1873 Assessment Roll for the Town of Edgewater John Austin’s property on Pennsylvania Avenue is described as one house on one acre of land, valued at $3,000, with the tax bill $45.00; “Paid” carefully noted on the roll.

Property Card, Staten Island, Block 2830, Lot 49. NYC Municipal Archives.

The Property Card series are another essential resource in the Archives for research about the built environment. As noted in many previous For the Record articles, the cards list ownership, conveyance, building classifications, and assessed valuation data, generally from the 1930s through the 1970s. Each card also includes a small photographic print (also known as the “tax photographs”). The card for the Austen confirms Austen’s loss of the property to the bank during the Great Depression.

The Landmarks Preservation Commission’s 1971 designation report focused on the architectural significance of the “picturesque and charming example of the Gothic Revival style of architecture.” Similarly, most news accounts about Alice Austen and her house failed to acknowledge Austen’s relationship with her life partner Gertrude Tate. More recently, works such as Yochelson’s book have painted a more complete picture of Austen’s life and her role in the LGBTQ community. Today, the Alice Austen House is a New York City and National Landmark, on the Register of Historic Places, a member of the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s distinctive group of Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios, and is a National site of LGBTQ+ History. The LGBT-NYC Sites Project provides a well-researched description of the house and the significance of Alice Austen.