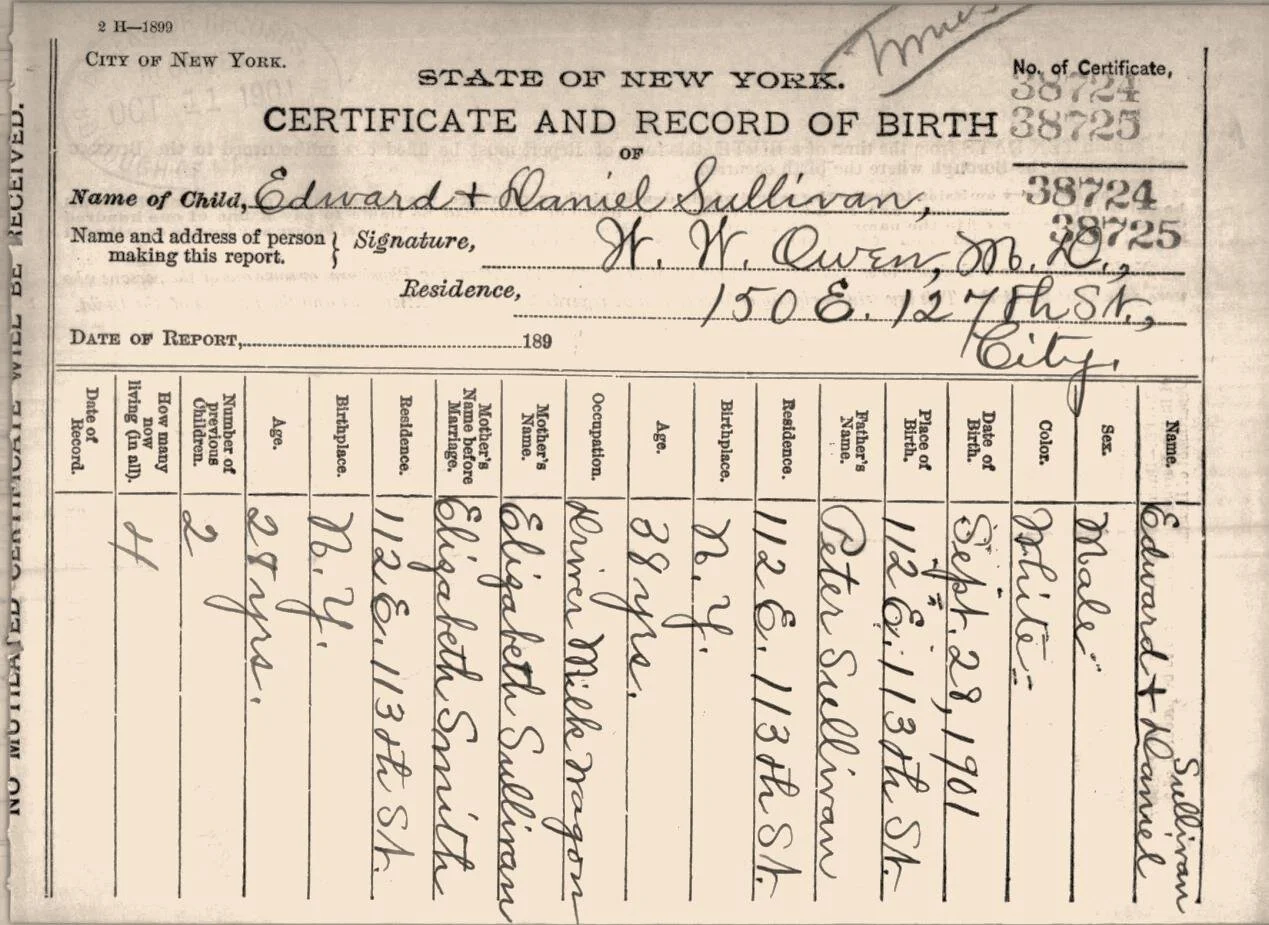

Recently, the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) asked the Municipal Archives to participate in a panel discussion The Birth of Identity: Race, Racism, and Personhood in New York City Health Records. Organized by Dr. Michelle Morse, Acting Commissioner and Chief Medical Officer of the DOHMH, the panelists explored the importance of birth certificates and how they record essential facts about a person’s identity. The panel also addressed how race data on birth records informs DOHMH work in pre-natal, maternal wellness, and health outcomes.

Dr. Morse extended the invitation when she learned about the Archives collection of records that document the births of enslaved children. They consist of more than 1,300 entries in local government records throughout the five Boroughs of New York City. These records had been created in response to the 1799 Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery in New York State. The Law stated that children born to enslaved women after July 4, 1799, would be legally freed after 25 years for women, and 28 years for men. In most instances, enslavers reported births of the children in recorded statements before Town clerks or other officials.

To prepare for the panel discussion, City archivists considered whether the Historical Vital Records (HVR) and related vital record ledger collections could potentially augment information about the enslaved children documented in the manumission records. Although vital records for the towns and villages in Brooklyn and Queens, where most of the manumissions took place, only date back to the early 1880s, research in the series is now significantly easier thanks to a completed digitization and indexing project.

Town of Newtown, Queens death ledger, 1881-1897. Historical Vital Record collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

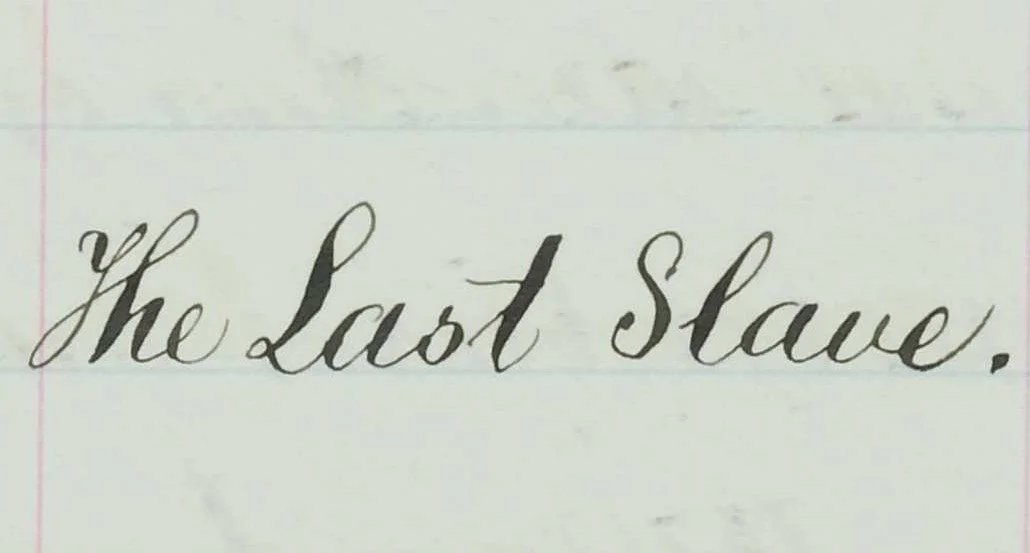

To test their theory, City archivists began reviewing the Town of Newtown, Queens, death ledger (1881-1897), and soon came across a startling entry: No. 982; date of death: March 2, 1885; name of deceased: George Rex; age: 89. In the column for “Occupation,” the clerk wrote, very clearly, “The Last Slave.” Oh!

Apparently, the clerk somehow knew that Mr. George Rex had been born enslaved and was described in his community as the last person with that background. The research journey that led to Mr. Rex was conveyed at the DOHMH panel, with a suggestion that further research in the Archives might provide “The Last Slave” with a greater sense of identity and dignity.

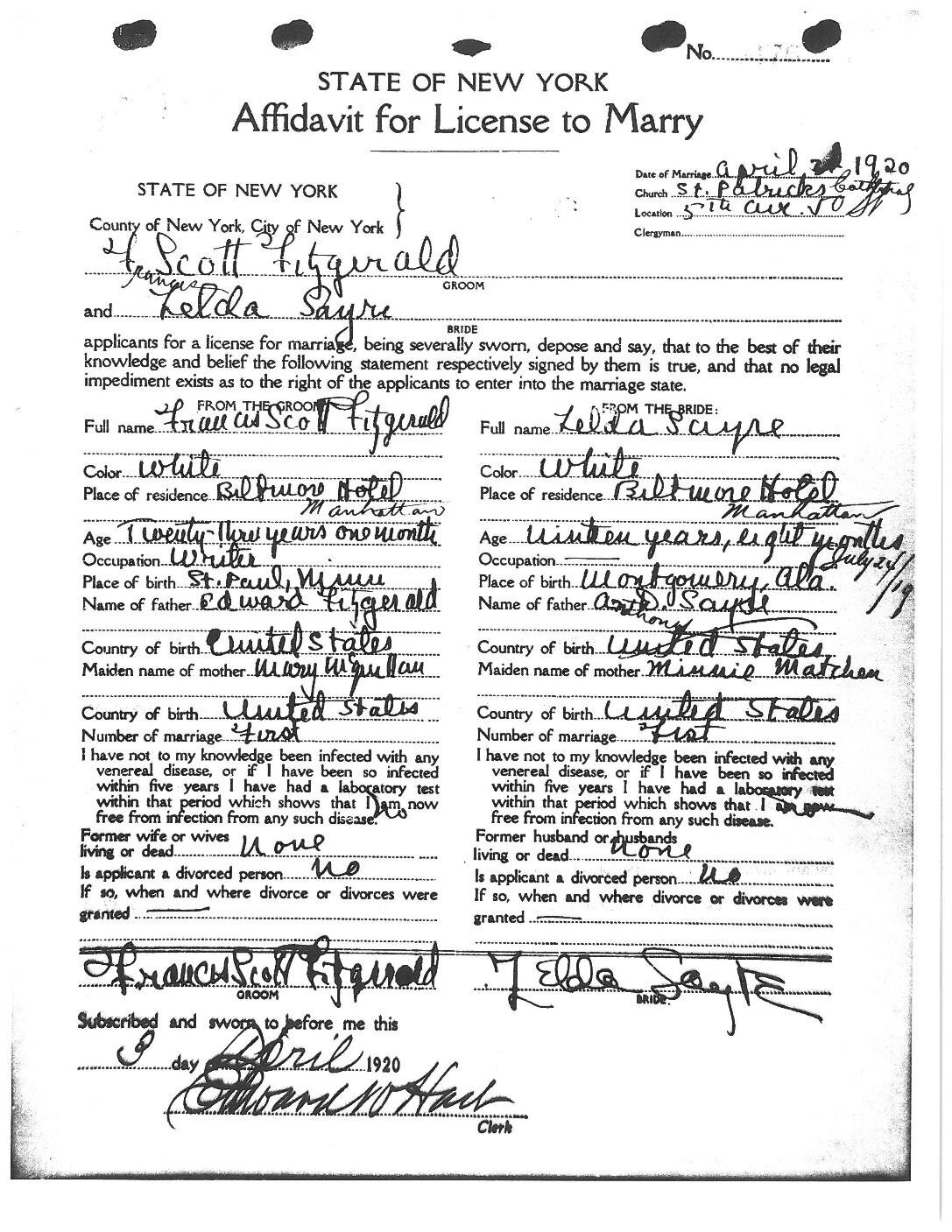

Subsequent to the panel discussion, City archivists began building a family tree for Mr. Rex. Based on his apparent renown in the community, it seemed possible that his death may have resulted in a local news article. And indeed it did. In fact, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle newspaper (digitized and available on-line via the Brooklyn Public Library) published several articles about Mr. Rex. “Frozen to Death,” ran on March 3, 1885. The subhead added, “George Recks, the Missing Negro, Found after Three Weeks’ Searching the Woodside, L.I. Woods.”

The story related that Recks is the “. . . aged negro who mysteriously disappeared from his home on Quincy Street, near Lewis Avenue [Brooklyn], about three weeks ago.” The story stated that he had been owned by the Rapelye family of Brooklyn and “. . . was believed to have been the last negro slave freed on Long Island.” It also added that George Reck’s father was named George Rex, after the then King of England, but the spelling of the family name had been changed to Recks.

Marriage certificate for Phoebe Ricks and Joseph Trower, 1879. Historical Vital Record collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

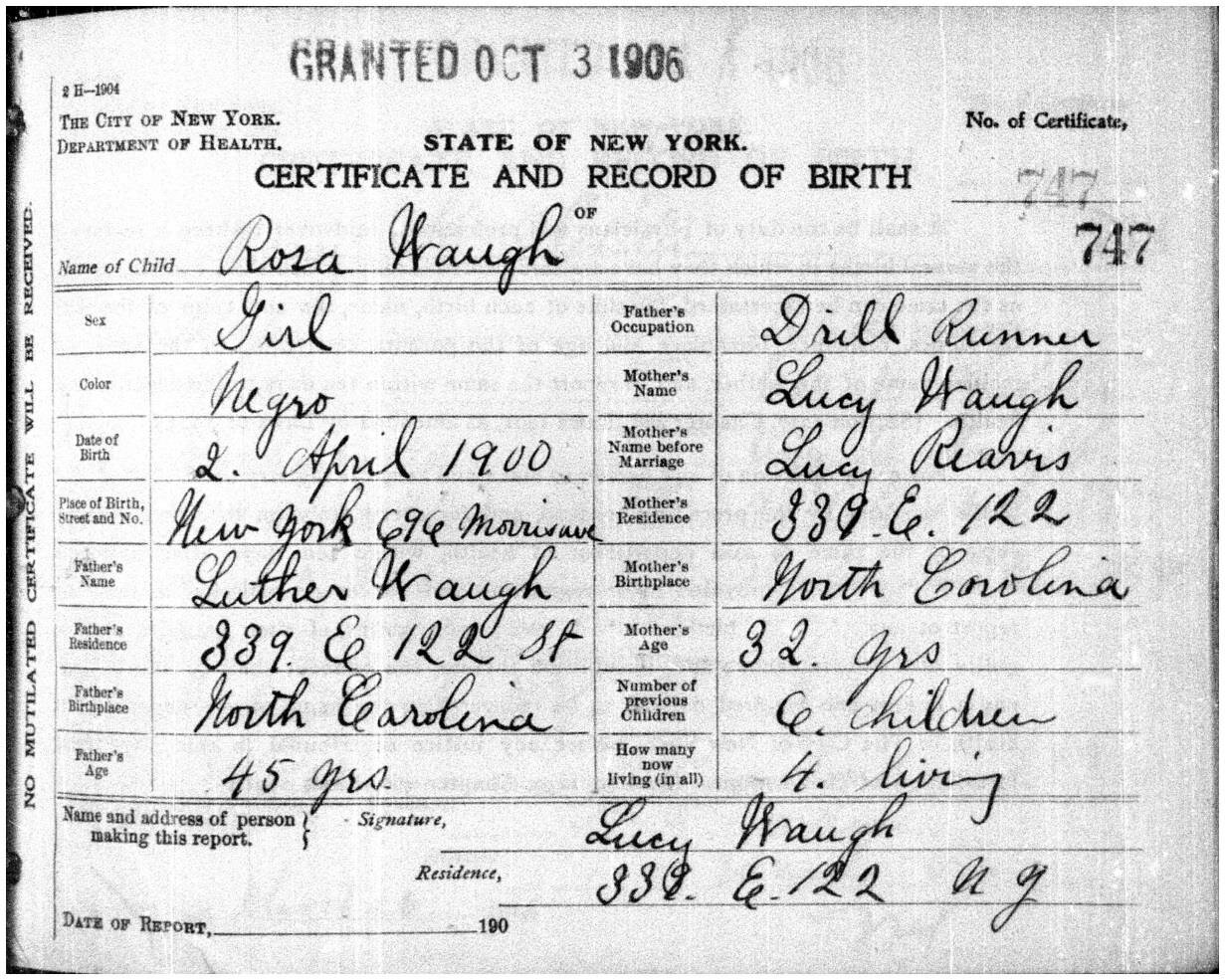

Would the Historical Vital Record (HVR) collection provide a greater identity and more information about Mr. George Rex/Recks? The answer is yes. The newspaper article stated that Recks had been the father-in-law of “J. C. Trower.” With that clue, archivists quickly located the 1879 marriage of Phoebe Ricks to Mr. Joseph Trower. The marriage certificate confirmed Pheobe’s parents, George Ricks and Isabella Crips. (The name was variously spelled as Ricks or Recks in the vital records.)

Continuing to search in the HVR, looking for death records indexed as Recks/Ricks resulted in the death certificate of George’s wife Isabella Crips, on July 4, 1871. According to the certificate, she had been born in Virginia in 1809, and her place of death, Quincy Street, near Stuyvesant Avenue, matched George’s residence. The certificate also indicated that Isabella was buried at the “Weekesville” Cemetery. One of the largest free Black communities in pre-Civil War America, Weekesville is currently an historic site and cultural center in Central Brooklyn.

The HVR index also led to information about George and Isabella’s other children. In addition to Phoebe, they had at least two other daughters, Margaret and Jane. Their sons William, Thomas and Peter all died at a young age.

Death certificate for George’s son, Thomas Rix, 1862. Historical Vital Record collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Continuing research on Phoebe and James Trower, revealed that they had at least two sons, Walter and Herbert. Both lived, married and died in Brooklyn; their records consistently stated Mother’s name Phoebe Ricks, and Father’s Name Joseph A. Trower. Further research will focus on whether either of their sons had children. Perhaps these inquiries will lead to descendants of George Rex/Recks/Ricks alive today.

Other Municipal Archives collections have proved useful in confirming additional information about George Rex/Recks/Ricks, in particular his residence on Quincy Street in Brooklyn. On March 4, 1885, the Eagle published a follow-up article. The story related that “The deceased... was born on the farm where he died. Alderman Collins, for whom Recks worked as a gardener... will see that his body is given a proper burial.” The article added that “Mr. Collins’ wife is a daughter of Jeremiah J. Rapelye, who built for Recks a house on Quincy Street when that populous neighborhood was almost as lonely as Montauk Point.”

Annals of Newtown, 1852. Courtesy NYPL.

The Town of Newtown death ledger entry for George Rex’ death indicated his place of birth as “Trains Meadows on the Rapelye-Purdy Farm.” Seeking to know more about this reference led to a volume, Annals of Newtown, in the Municipal Library. The book included a map insert that showed the exact location of Trains Meadows, and that it bordered both the Rapelye and Purdy farms.

The Municipal Archives map collections and the Assessed Valuation of Real Estate ledgers confirmed the newspaper story about the Quincy Street house. The 1886 atlas of Brooklyn (Robinson’s) showed that the residence was clearly within the boundaries of what had been the Rapelye farmland in Brooklyn. The assessed valuation of real estate ledgers for Brooklyn also corroborated the news account. The Brooklyn 19th century assessment records are arranged by Ward number and further by block and lot numbers. The related series of Ward Maps helped identify the necessary numbers for the Quincy Street property: Ward 9 (later Ward 21), block 192, lot 18.

Robinson’s Atlas of Brooklyn, 1886. NYC Municipal Archives.

Unlike the Manhattan annual assessment ledgers, each Brooklyn book spans several years. The Ward 21 ledger for 1869 through 1873, lists “J. Rapelye” as the “owner” of block 192, lot 8. Under “description of property” the clerk scribbled what looks like the number “2” indicating a two-story structure. According to later assessment records, within a few years after the death of George Rex, his property had been divided into lots and sold for residences.

Record of Assessed Valuation, Brooklyn, Ward 21 for 1869 through 1873. NYC Municipal Archives.

George Rex’s house, lot 18, sat in the corner of what had been the Rapelye farm. Robinson’s Atlas of Brooklyn, 1886. NYC Municipal Archives.

Returning to information in the Newtown death ledger, under “cause of death” the clerk wrote “Inquest Pending” by medical attendant Coroner O’Connell. The Archives Old Town Records collection, recently processed with support from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, includes several ledgers created by town coroners including O’Connell. Regrettably, the oldest surviving ledger maintained by Coroner O’Connell only dates back to November 1885; several months after the death of George Rex. However, on March 4, 1885, the Brooklyn newspaper reported that the cause of death had been confirmed as exposure.

Record of Assessed Valuation, Brooklyn, Ward 9 Atlas, 1863. NYC Municipal Archives.

The Municipal Archives recently launched a transcription project that will greatly enhance access to the manumission records. Born before enactment of New York State’s law for gradual emancipation in 1799, George Rex’ name will not appear in that series. Using the Old Town records, vital records and other collections, it may be possible to identify and develop fuller histories of other member of the Rex family.

The research will continue. Mr. George Rex, “The Last Slave” will not be forgotten!