This is the second in our series of ‘how to conduct research’ blogs in On the Record. It provides essential information about several lesser-known resources at the Municipal Archives that are relevant to the family historian or genealogist. This blog is adapted from a program “beyond the basics” Marcia Kirk recently recorded for a genealogy conference.

Most of the records discussed in this guide are available on microfilm at the Municipal Archives; a few have been digitized and are noted as such. The digitized records are available in our online gallery.

Coroners’ Records

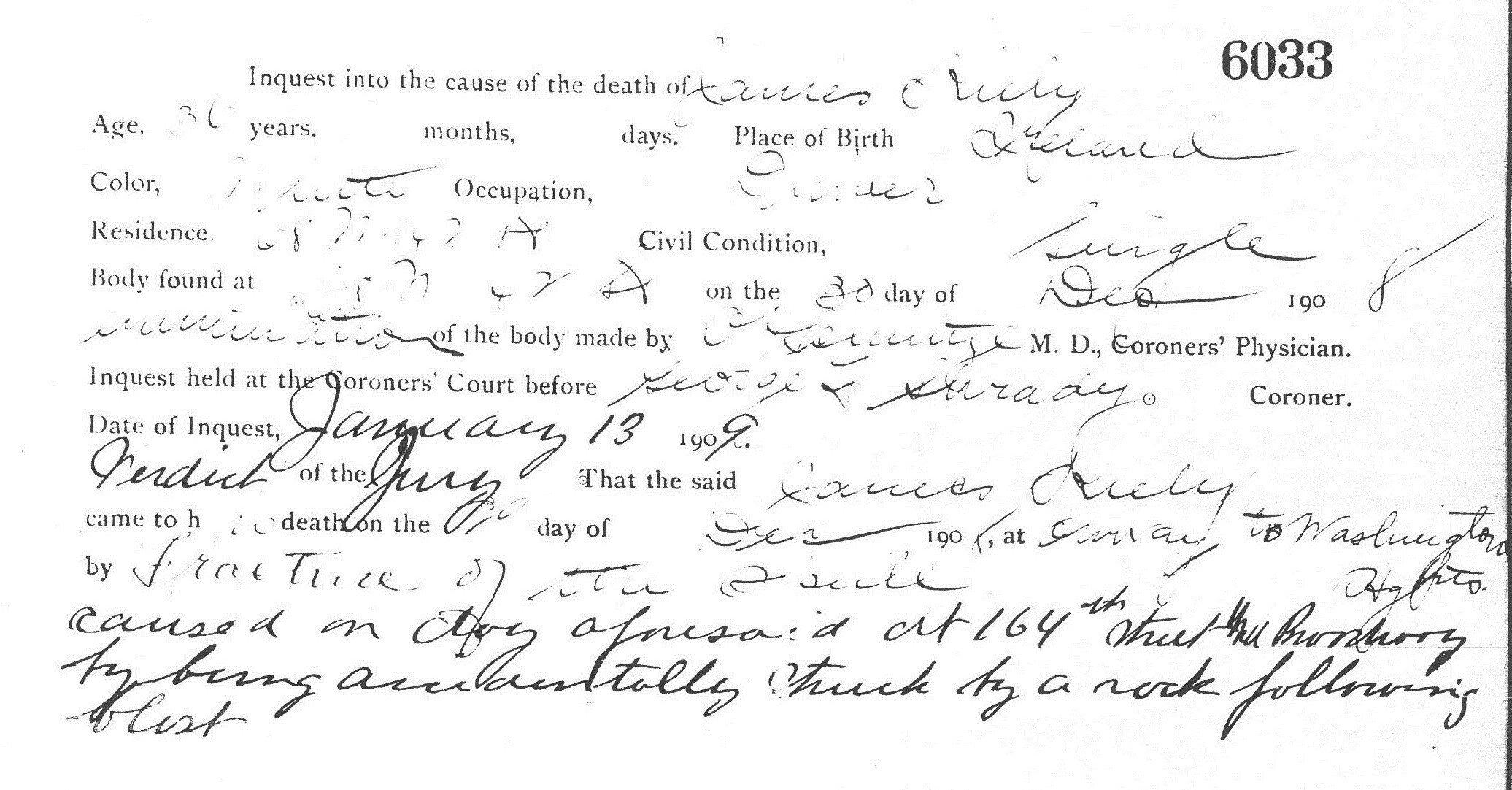

Coroners’ Inquest Records (also known as coroner’s reports) were created when a death was deemed suspicious. For example, if someone fell from a building, a Coroners’ inquest would be noted on the death certificate. The coroner record usually supplies more detailed information about the circumstances of a death than the death certificate filed by the Health Department.

They are available for all five boroughs from 1898 to 1917. For the period prior to consolidation in 1898, there are coroner records for Manhattan from 1853 to 1897; Kings County, from 1863 to 1896; and Queens from 1884 to 1897.

The ledger format coroner records for Manhattan are only available on microfilm. The Municipal Archives did not produce the microfilm and does not have the original ledgers. Some of the microfilm is a little difficult to read.

Coroner’s Inquest, January 13, 1909. The accidental death of a 36-year-old man, born in Ireland and struck by a rock “following blast” on December 30, 1908. Coroner’s Record Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Office of the Chief Medical Examiner

The Coroners’ Office was abolished by New York State law in 1915 and replaced with the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (OCME), effective January 1, 1918. This office still exists. The OCME records include three series: indexes, ‘Accession’ docket books, and documents. The records date from 1918 to 1950 and are extant for all five Boroughs.

The first step in locating an OCME record is to search the microfilmed index to the Accession dockets. The index provides the case file number. In step two, using the case file number, the entry can be researched in the Accession docket book, also on microfilm. The Accession docket lists the name of the deceased, date of death, place of last residence, age, where the body was found and/or place of death, who reported the death, and the cause of death.

The Municipal Archives collection also includes the documents filed by the OCME pertaining to the death. These include police reports and autopsies. Copies of the documents can be requested (contact familyhistory@records.nyc.gov for ordering and fee information).

OCME ‘Accession’ Docket, Manhattan, 1940. NYC Municipal Archives.

Bodies in Transit Registers

The Bodies in Transit Registers were created by the New York City (Manhattan) Department of Health. They date from 1859 to 1894.

This collection is digitized and available in the online gallery. Each body or corpse that came into, out of, or through Manhattan was recorded in the register. The entry includes the date the body transited through the city, the name of the deceased, age, cause of death, nativity, the name of the person accompanying the body, and the place of burial. For more information on this collection see our blog.

The registers list the body of John Brown on route to his burial in upstate New York, and Abraham Lincoln whose body lay in state at City Hall after his assassination. There are also many Civil War soldiers from both the north and the south listed in the registers. They had been killed in battle, or died from disease, and their bodies passed through Manhattan for burial in cemeteries outside the city.

Bodies in Transit Register, 1865. NYC Municipal Archives.

Bodies in Transit Register, 1865, see entry - Lincoln, Abraham, age: 56 years 2 months, birthplace: Kentucky; place of death: Washington, D.C., cause of death: pistol shot. NYC Municipal Archives.

Estate Inventories

The Municipal Archives maintains a collection of Estate Inventories that provide lists of all the possessions of the deceased as tallied by a court-appointed appraiser. The collection comprises two series: 1784 to 1836, and 1830 to 1859, and include persons who were residents of Manhattan only (New York County). These microfilmed records are indexed, searchable by the name of the decedent or the appraiser. Researchers should also consult with the New York County Surrogates’ Court, and the New York County Clerk’s Division of Old Records for other series pertaining to estates. See the table below for more information.

Estate Inventory, NYC Municipal Archives.

Letters of Guardianship

Another series that originated in the New York County Surrogate’s Court are the Letters of Guardianship. They date from 1811 to 1913. These are also Manhattan records and only available on microfilm. Each volume contains an index in the front of the volume.

Guardianship record, 1811. NYC Municipal Archives.

Almshouse Ledger Collection

History of Inmates, 1919. NYC Municipal Archives.

The Almshouse Ledgers are another fascinating collection which span 1758 to 1952. There are more than 400 volumes pertaining to the many city-run institutions on Blackwell Island, now named Roosevelt Island. They include the Almshouses, Lunatic Asylum, Workhouses, the Penitentiary, and various hospitals.

A sampling of the volumes from several different series have been digitized and are available in the online gallery. There is also a detailed finding aid for this collection with links to the digitized volumes. The finding aid explains the different series of records and the types of records available.

Inmate History, 1895. NYC Municipal Archives.

The “Record of Inmates” lists residents of the Almshouse institution, not persons who were imprisoned. One of the important things about the Record of Inmates, especially for those of Irish or German ancestry, is that it includes the county in which the person was born as well as the town/city. The series provides a wealth of information including the name, date of admission to the institution, when discharged, nativity, naturalization information, occupation, and often the name and address of a family member. It also provides the “Habits of the father,” e.g. “temp” (temperate) meaning the person did not drink. (Alcoholism was a big problem.) The record will also note if the person was self-supporting, or in the poorhouse. If they were in the poorhouse, the question was asked “for how long?”

New York County Jury Census

The Jury censuses were taken in 1816, 1819, and 1821. There is one volume for each Ward of the city; some volumes are missing. The purpose of the census was to determine eligibility to serve on a jury. The jury censuses have been digitized and are available online. There is also a finding aid for this collection.

The census records are arranged by ward and then by street. If the street address is not known, city directories can be consulted (available on the New York Public Library’s digital collections website).

The census includes both male and female heads of household. The census recorded the name of the head of the household, the house number and street, occupation, age, reason for exemption from serving on a jury (old age, etc.), and the total number of jurors in the particular household. The census designates white inhabitants, aliens, coloured (sic) inhabitants (not slaves), and Slaves and provides the total number of inhabitants in the household. (Slavery was not ended in New York State until 1827.)

1816 Jury Census, 1st Ward. Broadway numbers 1-58 containing 274 Inhabitants. NYC Municipal Archives.

Police Census

Most family historians are probably aware that the 1890 U.S. Federal census was almost completely destroyed in a fire. Thankfully, New York City took its own census that year. City officials believed the federal census undercounted the population. The Police census is often used as a substitute for the 1890 Federal Census.

The street address of the person or family must be known to search the census at the Archives; it is not indexed by name. The census lists everyone in the household, their gender, and age. There is a street address index available at the Archives that provides the census volume number.

1890 Census. NYC Municipal Archives.

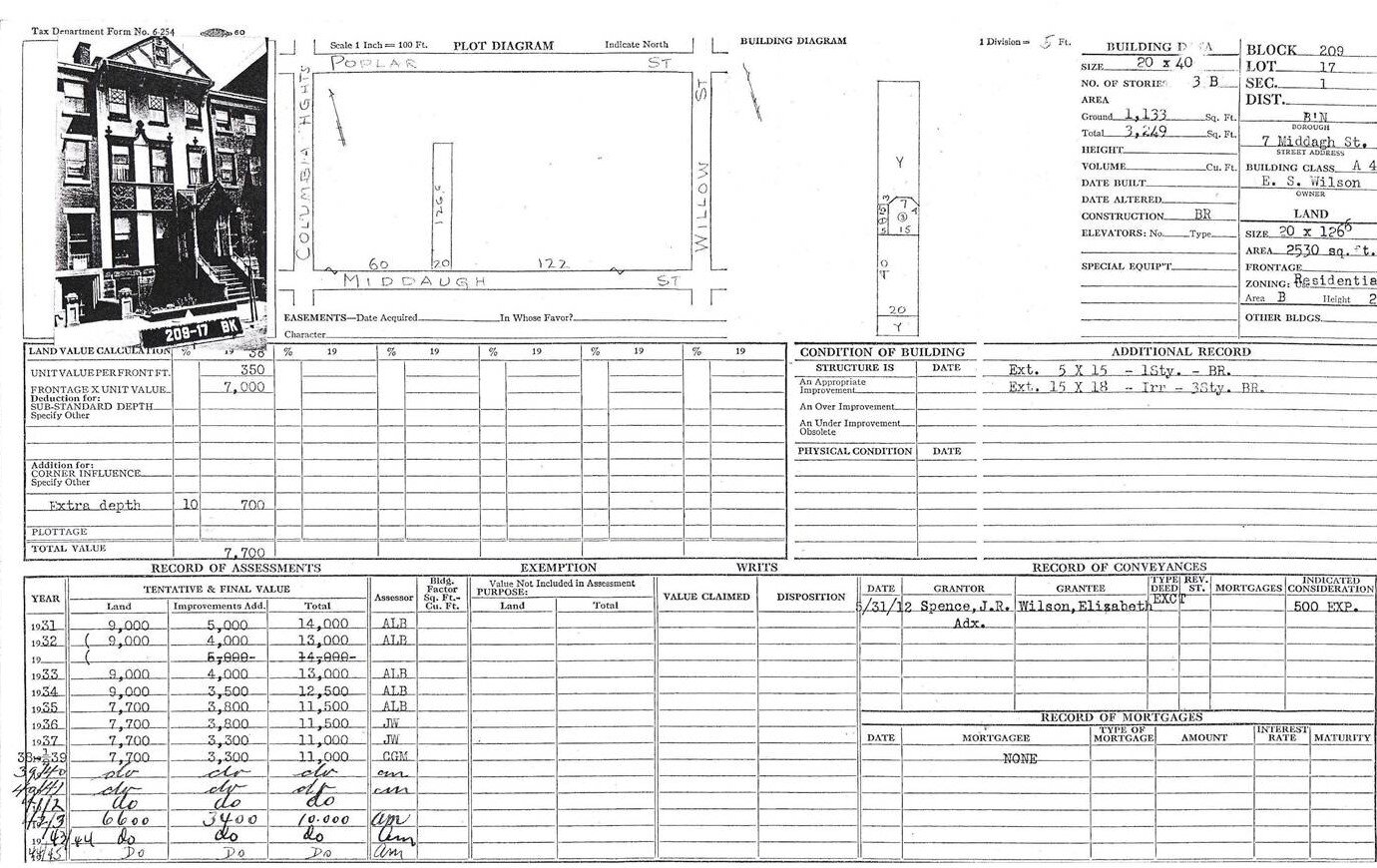

Property Cards

One of the Archives’ more popular collections is the Property Cards. With federal funding from the Works Progress Administration, the cards were created by the Department of Finance to modernize the tax assessment process. The cards date from 1939 and were continuously updated through 1990. All five boroughs are included.

There is a small photographic print of the property taken in the 1940s attached to the card. The assessed valuation, conveyances, and mortgages are also recorded. A diagram of the building and the plot, and other information about the building including the zoning, classification, and the block and lot number can also be found.

The creators of these records probably did not anticipate that people would be using them for genealogical research. Some people even give them as gifts. The cards have not been microfilmed or digitized; copies can be requested (contact familyhistory@records.nyc.gov for ordering and fee information).

Property Card, 7 Middagh Street, Brooklyn. NYC Municipal Archives.

Tax Photos

The photographs that appear on the property card also exist as a separate collection known as the “tax photographs.” The photographs have been digitized and can be viewed on the online gallery. There are two series of photographs: 1939 to 1941 (these images were affixed to the property card), and a second series dating from the mid-1980s.

The 1940s collection includes every building in all five boroughs except for empty lots and tax-exempt properties. The photos from the 1980s include empty lots and tax-exempt properties. There is a Guide to the 1940s Tax Department photographs available that provides additional information.

1940 ‘Tax’ Photograph, Queens Block 3176, Lot 45. NYC Municipal Archives.