Recently, Municipal Archives conservators began treating an oversize scrapbook of photographs taken in 1945. Located in the Grover Whalen papers, the evocative pictures capture the spontaneous joy expressed by New Yorkers as they welcomed home their sons and daughters and victorious war-time leaders.

Thousands of spectators lined the streets as General Dwight D. Eisenhower and his motorcade traveled through the City, June 19, 1945. Grover Whalen Papers, NYC Municipal Archives.

Known as the City’s “Official Greeter,” Whelan led the Mayor’s Office for Receptions to Distinguished Guests, a.k.a. the Mayor’s Reception Committee, from 1918 to 1953.

On June 19, 1945, just six weeks after hostilities in Europe ceased, Whalen and Reception Committee staff organized a reception for General Dwight D. Eisenhower. According to news reports the following day, crowds estimated at a half million gave a rapturous thank you to “Ike” as his motorcade made its way from LaGuardia Airport in Queens, to Manhattan, traveling down Fifth Avenue and Broadway and up the Canyon of Heroes. After a brief ceremony at City Hall and a luncheon at Gracie Mansion, Eisenhower’s motorcade brought him to a baseball game at Yankee Stadium. His whirlwind day concluded with a banquet at the Waldorf-Astoria. News articles noted that New Yorkers mostly ignored instructions from City officials to hold off on showering the victorious leader with paper, then still needed for the war-effort.

Baseball fans gave General Dwight D. Eisenhower a standing ovation as his motorcade entered Yankee Stadium, June 19, 1945. The Yankees played the Boston Red Sox. The Sox won, 1 – 0. Grover Whalen Papers, NYC Municipal Archives.

French war-time leader Charles F. De Gaulle greets the crowd from the steps of City Hall during his ticker-tape reception on August 27, 1945. Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia stands to his left at the microphones. Grover Whalen Papers, NYC Municipal Archives.

Two months later, on August 27, the Reception Committee let New Yorkers express their gratitude to the French leader Charles F. De Gaulle. Soon after, on September 13, the Committee organized a ticker-tape parade and welcome home ceremony for General Jonathan Wainwright. The Committee again used their considerable skill to stage welcome home events for Admiral Chester Nimitz on October 9, and Admiral William Halsey on December 14.

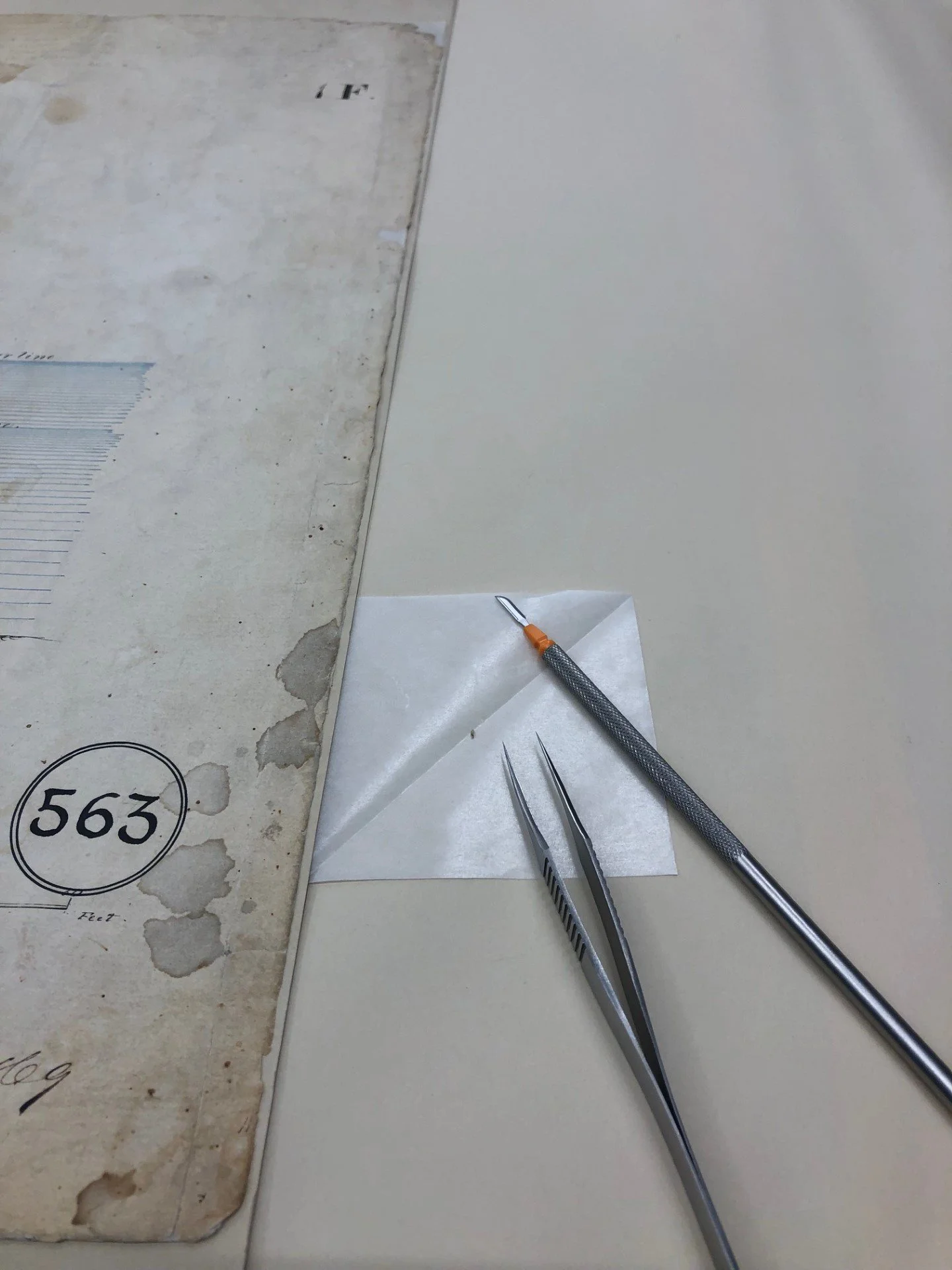

Reception Committee staff pasted pictures from the events on 30 large (18 by 24-inch) scrapbook pages; usually three or four to a sheet. They are not captioned. The paper has deteriorated but it may not be possible to remove the pictures without causing damage. For now, conservators will clean the photographs and re-house them in appropriate containers. Future digitization will provide public access.

For the Record readers are invited to review a selection of pictures from this unique artifact.

Young spectators seem awed by the passing spectacle. Grover Whalen Papers, NYC Municipal Archives.

Wounded service men and women watch the parade from indoors. Grover Whalen Papers, NYC Municipal Archives.

Thousands of New Yorkers crowded into City Hall Park to get a glimpse of General Dwight D. Eisenhower and hear his remarks during the reception on June 19, 1945. Grover Whalen Papers, NYC Municipal Archives.

Police officers struggle to contain the happy crowds along a parade route, 1945. Grover Whalen Papers, NYC Municipal Archives.

Spectators packed the sidewalk in front of the New York Public Library during a parade for returning service men and women, 1945. Grover Whalen Papers, NYC Municipal Archives.

General Jonathan Wainwright steps from the cabin of the ATC plane which brought him to LaGuardia Airport from Washington, D.C., September 13, 1945. Grover Whalen Papers, NYC Municipal Archives.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower addressed the crowd at his City Hall reception on June 19, 1945. Grover Whalen Papers, NYC Municipal Archives.

Police officers struggle to contain the happy crowds along a parade route. Grover Whalen Papers, NYC Municipal Archives.

A smiling New York City police officer helps keep the crowds at bay, 1945. Grover Whalen Papers, NYC Municipal Archives.

Tanks roll up lower Fifth Avenue during a parade for the returning soldiers and sailors, 1945. Grover Whalen Papers, NYC Municipal Archives.

Fleet Admiral William F. Halsey Jr, Commander of the Navy’s Third Fleet in World War II needed a blanket for warmth during his ticker-tape parade on a chilly December 14, 1945. Grover Whalen Papers, NYC Municipal Archives.

Soldiers and sailors flank City Greeter Grover Whalen, French leader Charles De Gaulle and Mayor Fiorello La Guardia as they exit City Hall following the reception ceremony on August 27, 1945. Grover Whalen Papers, NYC Municipal Archives. Grover Whalen Papers, NYC Municipal Archives.

A parade spectator leaps to greet General Jonathan Wainwright riding atop his limousine during the ticker-tape celebration along lower Broadway, September 13, 1945. Grover Whalen Papers, NYC Municipal Archives.